Festival Joshi en la tribu Kalash en Pakistán, 14 de mayo de 2011. Credit:Shutterstock/Maharani afifah

Abro los ojos al sonido de una voz mientras el avión de hélice bimotor de Pakistan Airlines vuela a través de la cordillera del Hindu Kush, al oeste de los imponentes Himalayas. Navegamos a 27.000 pies, pero las montañas que nos rodean parecen preocupantemente cercanas y la turbulencia me ha despertado durante un viaje de 22 horas al lugar más remoto de Pakistán:los valles Kalash de la región de Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

A mi izquierda, una pasajera angustiada reza en silencio. Inmediatamente a mi derecha se sienta mi guía, traductor y amigo Taleem Khan, miembro de la tribu politeísta Kalash, que cuenta con unas 3500 personas. Este era el hombre que me hablaba cuando me despertaba. Se inclina de nuevo y pregunta, esta vez en inglés:"Buenos días, hermano. ¿Estás bien?"

"Prúst", (estoy bien) respondo, mientras me vuelvo más consciente de mi entorno.

No parece que el avión esté descendiendo; más bien, se siente como si el suelo estuviera saliendo a nuestro encuentro. Y después de que el avión ha llegado a la pista y los pasajeros han desembarcado, el jefe de la comisaría de Chitral está allí para saludarnos. Nos asignan una escolta policial para nuestra protección (cuatro oficiales operando en dos turnos), ya que existen amenazas muy reales para investigadores y periodistas en esta parte del mundo.

Solo entonces podemos embarcarnos en la segunda etapa de nuestro viaje:un viaje en jeep de dos horas a los valles de Kalash por un camino de grava que tiene altas montañas a un lado y una caída de 200 pies al río Bumburet al otro. Los colores intensos y la vivacidad del lugar deben vivirse para entenderse.

El objetivo de este viaje de investigación, realizado por el Laboratorio de Música y Ciencias de la Universidad de Durham, es descubrir cómo la percepción emocional de la música puede verse influenciada por los antecedentes culturales de los oyentes, y examinar si existen aspectos universales en las emociones que transmite la música. . Para ayudarnos a entender esta pregunta, queríamos encontrar personas que no hubieran estado expuestas a la cultura occidental.

Los pueblos que van a ser nuestra base de operaciones están repartidos por tres valles en la frontera entre el noroeste de Pakistán y Afganistán. Son el hogar de varias tribus, aunque tanto a nivel nacional como internacional se les conoce como los valles Kalash (llamados así por la tribu Kalash). A pesar de su población relativamente pequeña, sus costumbres únicas, religión politeísta, rituales y música los distinguen de sus vecinos.

El camino de Chitral al valle central de Kalash. Crédito:George Athanasopoulos, proporcionado por el autor

En el campo

He realizado investigaciones en lugares como Papúa Nueva Guinea, Japón y Grecia. La verdad es que el trabajo de campo suele ser costoso, potencialmente peligroso y, a veces, incluso mortal.

Pero por difícil que sea realizar experimentos cuando nos enfrentamos a barreras lingüísticas y culturales, la falta de un suministro eléctrico estable para cargar nuestras baterías sería uno de los obstáculos más difíciles de superar en este viaje. Los datos solo se pueden recopilar con la ayuda y la voluntad de la población local. Las personas que conocimos literalmente hicieron un esfuerzo adicional por nosotros (en realidad, 16 millas adicionales) para que pudiéramos recargar nuestro equipo en la ciudad más cercana con energía. Hay poca infraestructura en esta región de Pakistán. La planta de energía hidroeléctrica local proporciona 200 W para cada hogar por la noche, pero es propensa a fallas debido a los restos flotantes después de cada lluvia, lo que hace que deje de funcionar cada dos días.

Una vez que superamos los problemas técnicos, estábamos listos para comenzar nuestra investigación musical. Cuando escuchamos música, dependemos en gran medida de nuestra memoria de la música que hemos escuchado a lo largo de nuestras vidas. Las personas de todo el mundo usan diferentes tipos de música para diferentes propósitos. Y las culturas tienen sus propias formas establecidas de expresar temas y emociones a través de la música, al igual que han desarrollado preferencias por ciertas armonías musicales. Las tradiciones culturales determinan qué armonías musicales transmiten felicidad y, hasta cierto punto, cuánta disonancia armónica se aprecia. Piense, por ejemplo, en el estado de ánimo feliz de Here Comes the Sun de The Beatles y compárelo con la siniestra dureza de la partitura de Bernard Herrmann para la infame escena de la ducha en Psycho de Hitchcock.

Entonces, como nuestra investigación pretendía descubrir cómo la percepción emocional de la música puede verse influenciada por los antecedentes culturales de los oyentes, nuestro primer objetivo fue ubicar a los participantes que no estaban expuestos de manera abrumadora a la música occidental. Esto es más fácil decirlo que hacerlo, debido al efecto general de la globalización y la influencia que tienen los estilos musicales occidentales en la cultura mundial. Un buen punto de partida fue buscar lugares sin suministro eléctrico estable y con muy pocas estaciones de radio. Eso generalmente significaría una conexión a Internet deficiente o nula con acceso limitado a plataformas de música en línea o, de hecho, cualquier otro medio para acceder a la música global.

Uno de los beneficios de nuestra ubicación elegida fue que la cultura circundante no estaba orientada hacia el oeste, sino más bien en una esfera cultural completamente diferente. La cultura punjabi es la corriente principal en Pakistán, ya que los punjabi son el grupo étnico más grande. Pero la cultura Khowari domina en los valles de Kalash. Menos del 2% habla urdu, la lengua franca de Pakistán, como lengua materna. El pueblo Kho (una tribu vecina a los Kalash), suman alrededor de 300.000 y formaban parte del Reino de Chitral, un estado principesco que fue primero parte del Raj británico y luego de la República Islámica de Pakistán hasta 1969. El mundo occidental es visto por las comunidades de allí como algo "diferente", "extranjero" y "no propio".

El segundo objetivo era localizar personas cuya propia música consistiera en una tradición interpretativa nativa establecida en la que la expresión de la emoción a través de la música se realiza de una manera comparable a la occidental. Eso se debe a que, aunque intentábamos escapar de la influencia de la música occidental en las prácticas musicales locales, era importante que nuestros participantes entendieran que la música podría transmitir diferentes emociones.

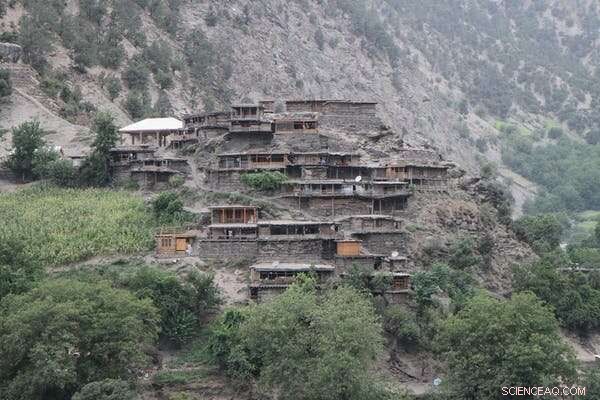

Viviendas de madera en el valle de Rumbur, uno de los tres valles habitados por el pueblo Kalash en el distrito de Chitral, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistán. Crédito:Shutterstock/knovakov

Finalmente, necesitábamos un lugar donde nuestras preguntas pudieran formularse de una manera que permitiera a los participantes de diferentes culturas evaluar la expresión emocional en la música occidental y no occidental.

Para los Kalash, la música no es un pasatiempo; es un identificador cultural. Es un aspecto inseparable de la práctica tanto ritual como no ritual, del nacimiento y de la vida. When someone dies, they are sent off to the sounds of music and dancing, as their life story and deeds are retold.

Meanwhile, the Kho people view music as one of the "polite" and refined arts. They use it to highlight the best aspects of their poetry. Their evening gatherings, typically held after dark in the homes of prominent members of the community, are comparable to salon gatherings in Enlightenment Europe, in which music, poetry and even the nature of the act and experience of thought are discussed. I was often left to marvel at how regularly men, who seemingly could bend steel with their piercing gaze, were moved to tears by a simple melody, a verse, or the silence which followed when a particular piece of music had just ended.

It was also important to find people who understood the concept of harmonic consonance and dissonance—that is, the relative attractiveness and unattractiveness of harmonies. This is something which can be easily done by observing whether local musical practices include multiple, simultaneous voices singing together one or more melodic lines. After running our experiments with British participants, we came to the Kalash and Kho communities to see how non-western populations perceive these same harmonies.

Our task was simple:expose our participants from these remote tribes to voice and music recordings which varied in emotional intensity and context, as well as some artificial music samples we had put together.

Major and minor

A mode is the language or vocabulary that a piece of music is written in, while a chord is a set of pitches which sound together. The two most common modes in western music are major and minor. Here Comes the Sun by The Beatles is a song in a major scale, using only major chords, while Call Out My Name by the Weeknd is a song in a minor scale, which uses only minor chords. In western music, the major scale is usually associated with joy and happiness, while the minor scale is often associated with sadness.

Right away we found that people from the two tribes were reacting to major and minor modes in a completely different manner to our UK participants. Our voice recordings, in Urdu and German (a language very few here would be familiar with), were perfectly understood in terms of their emotional context and were rated accordingly. But it was less than clear cut when we started introducing the musical stimuli, as major and minor chords did not seem to get the same type of emotional reaction from the tribes in northwest Pakistan as they do in the west.

We began by playing them music from their own culture and asked them to rate it in terms of its emotional context; a task which they performed excellently. Then we exposed them to music which they had never heard before, ranging from West Coast Jazz and classical music to Moroccan Tuareg music and Eurovision pop songs.

While commonalities certainly exist—after all, no army marches to war singing softly, and no parent screams their children to sleep—the differences were astounding. How could it be that Rossini's humorous comic operas, which have been bringing laughter and joy to western audiences for almost 200 years, were seen by our Kho and Kalash participants to convey less happiness than 1980s speed metal?

We were always aware that the information our participants provided us with had to be placed in context. We needed to get an insider perspective on their train of thought regarding the perceived emotions.

Essentially, we were trying to understand the reasons behind their choices and ratings. After countless repetitions of our experiments and procedures and making sure that our participants had understood the tasks that we were asking them to do, the possibility started to emerge that they simply did not prefer the consonance of the most common western harmonies.

Not only that, but they would go so far as to dismiss it as sounding "foreign." Indeed, a recurring trope when responding to the major chord was that it was "strange" and "unnatural," like "European music." That it was "not our music."

What is natural and what is cultural?

Once back from the field, our research team met up and together with my colleagues Dr. Imre Lahdelma and Professor Tuomas Eerola we started interpreting the data and double checking the preliminary results by putting them through extensive quality checks and number crunching with rigorous statistical tests. Our report on the perception of single chords shows how the Khalash and Kho tribes perceived the major chord as unpleasant and negative, and the minor chord as pleasant and positive.

To our astonishment, the only thing the western and the non-western responses had in common was the universal aversion to highly dissonant chords. The finding of a lack of preference for consonant harmonies is in line with previous cross-cultural research investigating how consonance and dissonance are perceived among the Tsimané, an indigenous population living in the Amazon rainforest of Bolivia with limited exposure to western culture. Notably, however, the experiment conducted on the Tsimané did not include highly dissonant harmonies in the stimuli. So the study's conclusion of an indifference to both consonance and dissonance might have been premature in the light of our own findings.

When it comes to emotional perception in music, it is apparent that a large amount of human emotions can be communicated across cultures at least on a basic level of recognition. Listeners who are familiar with a specific musical culture have a clear advantage over those unfamiliar with it—especially when it comes to understanding the emotional connotations of the music.

But our results demonstrated that the harmonic background of a melody also plays a very important role in how it is emotionally perceived. See, for example, Victor Borge's Beethoven variation on the melody of Happy Birthday, which on its own is associated with joy, but when the harmonic background and mode changes the piece is given an entirely different mood.

Then there is something we call "acoustic roughness," which also seems to play an important role in harmony perception—even across cultures. Roughness denotes the sound quality that arises when musical pitches are so close together that the ear cannot fully resolve them. This unpleasant sound sensation is what Bernard Herrmann so masterfully uses in the aforementioned shower scene in Psycho. This acoustic roughness phenomenon has a biologically determined cause in how the inner ear functions and its perception is likely to be common to all humans.

According to our findings, harmonisations of melodies that are high in roughness are perceived to convey more energy and dominance—even when listeners have never heard similar music before. This attribute has an affect on how music is emotionally perceived, particularly when listeners lack any western associations between specific music genres and their connotations.

For example, the Bach chorale harmonization in major mode of the simple melody below was perceived as conveying happiness only to our British participants. Our Kalash and Kho participants did not perceive this particular style to convey happiness to a greater degree than other harmonisations.

The wholetone harmonization below, on the other hand, was perceived by all listeners—western and non-western alike—to be highly energetic and dominant in relation to the other styles. Energy, in this context, refers to how music may be perceived to be active and "awake," while dominance relates to how powerful and imposing a piece of music is perceived to be.

Carl Orff's O Fortuna is a good example of a highly energetic and dominant piece of music for a western listener, while a soft lullaby by Johannes Brahms would not be ranked high in terms of dominance or energy. At the same time, we noted that anger correlated particularly well with high levels of roughness across all groups and for all types of real (for example, the Heavy Metal stimuli we used) or artificial music (such as the wholetone harmonization below) that the participants were exposed to.

So, our results show both with single, isolated chords and with longer harmonisations that the preference for consonance and the major-happy, minor-sad distinction seems to be culturally dependent. These results are striking in the light of tradition handed down from generation to generation in music theory and research. Western music theory has assumed that because we perceive certain harmonies as pleasant or cheerful this mode of perception must be governed by some universal law of nature, and this line of thinking persists even in contemporary scholarship.

Indeed, the prominent 18th century music theorist and composer Jean-Philippe Rameau advocated that the major chord is the "perfect" chord, while the later music theorist and critic Heinrich Schenker concluded that the major is "natural" as opposed to the "artificial" minor.

But years of research evidence now shows that it is safe to assume that the previous conclusions of the "naturalness" of harmony perception were uninformed assumptions, and failed even to attempt to take into account how non-western populations perceive western music and harmony.

Just as in language we have letters that build up words and sentences, so in music we have modes. The mode is the vocabulary of a particular melody. One erroneous assumption is that music consists of only the major and minor mode, as these are largely prevalent in western mainstream pop music.

In the music of the region where we conducted our research, there are a number of different, additional modes which provide a wide range of shades and grades of emotion, whose connotation may change not only by core musical parameters such as tempo or loudness, but also by a variety of extra-musical parameters (performance setting, identity, age and gender of the musicians).

For example, a video of the late Dr. Lloyd Miller playing a piano tuned in the Persian Segah dastgah mode shows how so many other modes are available to express emotion. The major and minor mode conventions that we consider as established in western tonal music are but one possibility in a specific cultural framework. They are not a universal norm.

Why is this important?

Research has the potential to uncover how we live and interact with music, and what it does to us and for us. It is one of the elements that makes the human experience more whole. Whatever exceptions exist, they are enforced and not spontaneous, and music, in some form, is present in all human cultures. The more we investigate music around the world and how it affects people, the more we learn about ourselves as a species and what makes us feel .

Our findings provide insights, not only into intriguing cultural variations regarding how music is perceived across cultures, but also how we respond to music from cultures which are not our own. Can we not appreciate the beauty of a melody from a different culture, even if we are ignorant to the meaning of its lyrics? There are more things that connect us through music than set us apart.

When it comes to musical practices, cultural norms can appear strange when viewed from an outsider's perspective. For example, we observed a Kalash funeral where there was lots of fast-paced music and highly-energetic dancing. A western listener might wonder how it is possible to dance with such vivacity to music which is fast, rough and atonal—at a funeral.

But at the same time, a Kalash observer might marvel at the sombreness and quietness of a western funeral:was the deceased a person of so little importance that no sacrifices, honorary poems, praise songs and loud music and dancing were performed in their memory? As we assess the data captured in the field a world away from our own, we become more aware of the way music shapes the stories of the people who make it, and how it is shaped by culture itself.

After we had said our goodbyes to our Kalash and Kho hosts, we boarded a truck, drove over the dangerous Lowari Pass from Chitral to Dir, and then traveled to Islamabad and on to Europe. And throughout the trip, I had the words of a Khowari song in my mind:"The old path, I burn it, it is warm like my hands. In the young world, you will find me."