El presidente de los Estados Unidos, Donald Trump, hizo afirmaciones falsas de fraude electoral generalizado durante las elecciones presidenciales de 2020. Los investigadores de UNSW Psychology ahora han encontrado una manera para que las personas no sean engañadas con las llamadas "noticias falsas" de una sola fuente. Crédito:Shutterstock

Si más personas te dijeran que algo es cierto, pensarías que tenderías a creerlo.

No, según un estudio de 2019 de la Universidad de Yale que descubrió que las personas creen en una sola fuente de información que se repite en muchos canales (un 'falso consenso'), tan fácilmente como si varias personas les dijeran algo basado en muchas fuentes originales independientes (un 'consenso verdadero').

El hallazgo mostró cómo se puede reforzar la información errónea y tuvo ramificaciones para las decisiones importantes que tomamos en función de los consejos que recibimos de lugares como gobiernos y medios sobre información como vacunas, uso de máscaras durante la pandemia o incluso a quién votamos en una elección. .

El hallazgo de la 'ilusión de consenso' de 2019 ha fascinado a la asociada de investigación postdoctoral en la Facultad de Psicología de Ciencias de la UNSW, Saoirse Connor Desai, quien probó el hallazgo de la ilusión y encontró una manera para que las personas no sean engañadas con las llamadas 'noticias falsas' de un única fuente.

El estudio de su equipo ha sido publicado en Cognition .

"Descubrimos que la ilusión se puede reducir cuando brindamos a las personas información sobre cómo las fuentes originales usaron evidencia para llegar a sus conclusiones", dice el Dr. Connor Desai.

Ella dice que el hallazgo es particularmente relevante para las mejores prácticas de comunicación científica, p. cómo los formuladores de políticas o los medios presentan a las personas evidencia o investigación científica experta.

Por ejemplo, más del 80 % de los blogs que niegan el cambio climático repiten afirmaciones de una sola persona que dice ser un "experto en osos polares".

"Podría haber una situación en la que una propuesta de salud engañosa se repita a través de múltiples canales, lo que podría influir en las personas para que confíen en esa información más de lo que deberían, porque creen que hay evidencia de eso, o creen que hay un consenso". dice el Dr. Connor Desai.

"Pero nuestro hallazgo muestra que si puede explicar a las personas de dónde proviene su información y cómo las fuentes originales llegaron a sus conclusiones, eso fortalece su capacidad para identificar un 'consenso verdadero'".

La Dra. Connor Desai dice que el hallazgo del estudio de Yale la sorprendió, "porque parecía ser una acusación de la capacidad humana para distinguir entre el verdadero consenso y el falso consenso".

"El estudio original mostró que las personas suelen ser malas en esto. Hubo muchas situaciones en las que nunca pudieron diferenciar entre el consenso verdadero y el falso", dice.

"Es problemático porque si las personas escuchan declaraciones falsas o engañosas de una sola persona repetidas a través de diferentes canales, pueden sentir que la declaración es más válida de lo que es".

Dr. Connor Desai says an example of this is multiple independent experts agreeing that Ivermectin should not be used to treat COVID-19 (true consensus), versus a single group or individual saying that people should use it as an anti-viral drug (false consensus).

How the study was conducted

The aim of the UNSW study was to understand why people believe false information when it's repeated.

"Our main goal was to establish whether one reason that people are equally convinced by true and false consensus is that they assume that different sources share data or methodologies," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Do they understand there is potentially more evidence when you have multiple experts saying the same thing?"

The UNSW researchers conducted several experiments.

The first experiment replicated the 2019 Yale study, which saw participants given a variety of articles about a fictional tax policy which took positive, negative, or neutral stances, and then asked to what extent they agreed the proposal would improve the economy.

It replicated the "illusion of consensus" where people are equally convinced by one piece of evidence as they are by many pieces of evidence but added a new condition where they told people who saw a "true consensus" that the sources had used different data and methods to arrive at their conclusions.

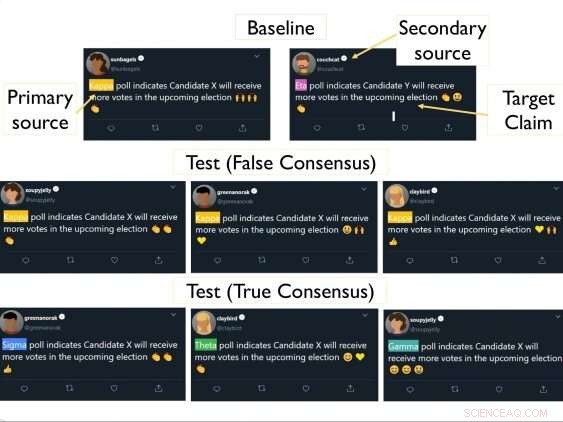

An example of the made up Twitter posts used in the study.

The result was a reduction in the illusion of consensus.

"People were more convinced by true consensus than false consensus."

In another experiment, 200 participants were given information about an election in a fictional foreign democratic country.

They were shown fictional Twitter posts from news outlets that said which candidates would get more votes in the election:some sourced the same or different pollsters to predict a candidate would win, while another tweet said a different contender would win.

But in the true consensus Twitter posts, they gave people a scenario in which it was clear that different primary sources worked independently and used different data to arrive at their conclusions.

"We expected that many people would be more familiar with such polls and would realize that looking at multiple different polls would be a better way of predicting the election result than just seeing a single poll multiple times," Dr. Connor Desai says.

After reading the tweets, participants rated which candidate would win based on the polling predictions.

"It seemed that people were more convinced by a true consensus than a false consensus when they understood the pollsters had gathered evidence independently of one another," Professor of Cognitive Psychology in the School of Psychology, Brett Hayes says.

"Our results suggest that people do see claims endorsed by multiple sources as stronger when they believe these sources really are independent of one another."

The researchers later replicated and extended the tweet study with 365 more participants.

"This time we had a condition where the tweets came from individual people who showed their endorsement of the polls using emojis," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Regardless of whether the tweets came from news outlets, or individual tweeters, people were more convinced by true than false consensus when the relationship between sources was unambiguous."

False consensus not completely discounted

But the researchers also found the participants didn't completely discount false consensus.

"There are at least two possible explanations for this effect," Dr. Connor Desai said.

"The first is that such repetition simply increases the familiarity of the claim—enhancing its memory representation, and this is sufficient to increase confidence.

"The second is that people may make inferences about why a claim is repeated because the source believed it was the most reputable or provided the strongest evidence.

"For instance, if different news channels all cite the same expert you might think that they're citing the same person because they are the most qualified to talk about whatever it is they're talking about."

Dr. Connor Desai plans to next look at why some communication strategies are more effective than others, and if repeating information is always effective.

"Is there a point where there's too much consensus, and people become suspicious?" she says.

"Can you correct a 'false consensus' by pointing out that it's often better to get information from multiple independent sources? These are the kinds of strategies we wish to look into."