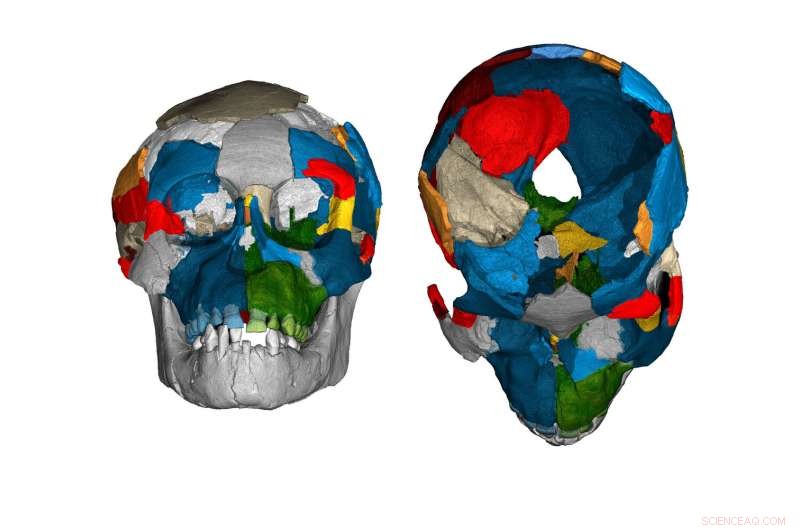

Huellas cerebrales en cráneos fósiles de la especie Australopithecus afarensis (famoso por "Lucy" y el "niño Dikika" de Etiopía en la foto) arrojan nueva luz sobre la evolución del crecimiento y la organización del cerebro. La huella endocraneal excepcionalmente conservada del niño Dikika revela una organización cerebral similar a la de un simio, y sin características derivadas de los humanos. Crédito:Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig.

Los científicos han podido medir y analizar durante mucho tiempo los cráneos fósiles de nuestros ancestros antiguos para estimar el volumen y el crecimiento del cerebro. La cuestión de cómo se comparan estos cerebros antiguos con los cerebros humanos modernos y con los cerebros de nuestro primo primate más cercano, el chimpancé, sigue siendo un objetivo importante de investigación.

Un nuevo estudio publicado en Avances de la ciencia usó tecnología de escaneo por tomografía computarizada para ver huellas cerebrales de tres millones de años dentro de cráneos fósiles de la especie Australopithecus afarensis (famoso por "Lucy" y "Selam" de la región de Afar de Etiopía) para arrojar nueva luz sobre la evolución de la organización y el crecimiento del cerebro. La investigación revela que, si bien la especie de Lucy tenía una estructura cerebral parecida a la de un simio, el cerebro tardó más en alcanzar el tamaño adulto, sugiriendo que los bebés pueden haber tenido una dependencia más prolongada de los cuidadores, un rasgo parecido al humano.

La tomografía computarizada permitió a los investigadores llegar a dos preguntas de larga data que no podían responderse solo con la observación visual y la medición:¿hay evidencia de una reorganización del cerebro similar a la humana en Australopithecus afarensis , y ¿el patrón de crecimiento del cerebro en esta especie era más similar al de los chimpancés o al de los humanos?

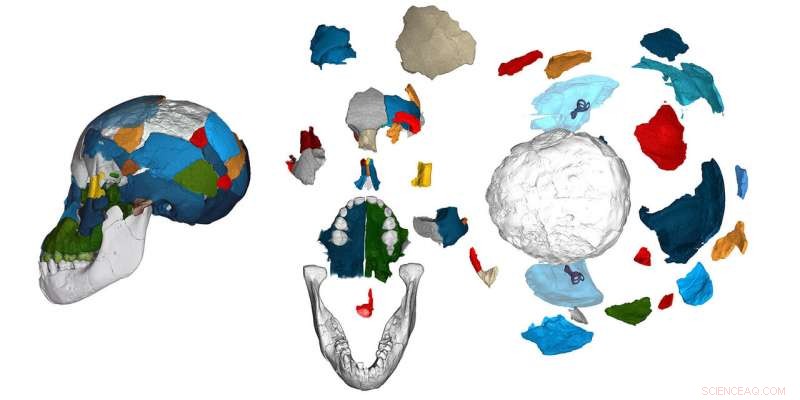

Estudiar el crecimiento y la organización del cerebro en A. afarensis , los investigadores, incluido el paleoantropólogo de ASU William Kimbel, escaneó ocho cráneos fósiles de los sitios etíopes de Dikika y Hadar utilizando tomografía computarizada convencional y sincrotrón de alta resolución. Kimbel, líder del trabajo de campo en Hadar, es directora del Instituto de Orígenes Humanos y profesora Virginia M. Ullman de Historia Natural y Medio Ambiente en la Escuela de Evolución Humana y Cambio Social.

La especie de Lucy habitó África oriental hace más de tres millones de años (se estima que la propia "Lucy" tiene 3,2 millones de años) y ocupa una posición clave en el árbol genealógico de los homínidos. ya que se acepta ampliamente que es ancestral de todos los homínidos posteriores, incluido el linaje que condujo a los humanos modernos.

"Lucy y sus parientes proporcionan evidencia importante sobre el comportamiento de los primeros homínidos:caminaban erguidos, tenían cerebros que eran alrededor de un 20 por ciento más grandes que los de los chimpancés, y pudo haber usado herramientas afiladas de piedra, "explica el coautor Zeresenay Alemseged (Universidad de Chicago), quien dirige el proyecto de campo Dikika en Etiopía y es un afiliado de investigación internacional del Instituto de Orígenes Humanos.

Los cerebros no se fosilizan, pero a medida que el cerebro crece y se expande antes y después del nacimiento, los tejidos que rodean su capa externa dejan una huella en el interior de la caja cerebral ósea. Los cerebros de los humanos modernos no solo son mucho más grandes que los de nuestros parientes simios vivos más cercanos, sino que también están organizados de manera diferente y tardan más en crecer y madurar. Comparado con los chimpancés, Los bebés humanos modernos aprenden durante más tiempo y dependen por completo del cuidado de sus padres durante períodos de tiempo más prolongados. Juntos, estas características son importantes para la cognición humana y el comportamiento social, pero sus orígenes evolutivos siguen sin estar claros.

Los cerebros no se fosilizan, pero a medida que el cerebro crece, los tejidos que rodean su capa externa dejan una huella en la caja cerebral ósea. La huella endocraneal del niño Dikika revela una organización cerebral similar a la de un simio, y sin características derivadas de los humanos. Crédito:Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Las tomografías computarizadas dieron como resultado "endocasts" digitales de alta resolución del interior de los cráneos, donde se puede visualizar y analizar la estructura anatómica del cerebro. Basado en estos endocasts, los investigadores pudieron medir el volumen cerebral e inferir aspectos clave de la organización cerebral a partir de impresiones de la estructura del cerebro.

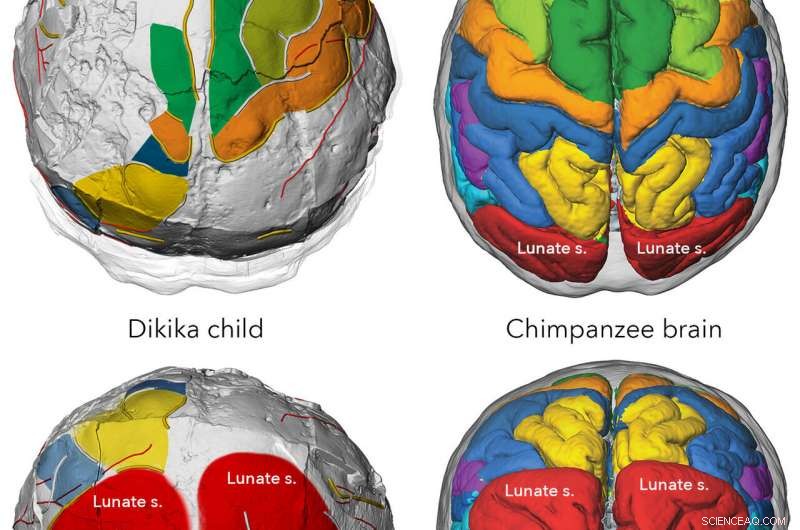

A key difference between apes and humans involves the organization of the brain's parietal lobe—important in the integration and processing of sensory information—and occipital lobe in the visual center at the rear of the brain. The exceptionally preserved endocast of "Selam, " a skull and associated skeleton of an Australopithecus afarensis infant found at Dikika in 2000, has an unambiguous impression of the lunate sulcus—a fissure in the occipital lobe marking the boundary of the visual area that is more prominent and located more forward in apes than in humans—in an ape-like position. The scan of the endocranial imprint of an adult A. afarensis fossil from Hadar (A.L. 162-28) reveals a previously undetected impression of the lunate sulcus, which is also in an ape-like position.

Some scientists had conjectured that human-like brain reorganization in australopiths was linked to behaviors that were more complex than those of their great ape relatives (e.g., stone-tool manufacture, mentalizing, and vocal communication). Desafortunadamente, the lunate sulcus typically does not reproduce well on endocasts, so there was unresolved controversy about its position in Australopithecus .

Brain imprints (shown in white) in fossil skulls of the species Australopithecus afarensis shed new light on the evolution of brain growth and organization. Several years of painstaking fossil reconstruction, and counting of dental growth lines, yielded an exceptionally preserved brain imprint of the Dikika child, and a precise age at death. Credit:Philipp Gunz, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

"A highlight of our work is how cutting-edge technology can clear up long-standing debates about these three million-year-old fossils, " notes coauthor Kimbel. "Our ability to 'peer' into the hidden details of bone and tooth structure with CT scans has truly revolutionized the science of our origins."

A comparison of infant and adult endocranial volumes also indicates more human-like protracted brain growth in Australopithecus afarensis , likely critical for the evolution of a long period of childhood learning in hominins.

In infants, CT scans of the dentition make it possible to determine an individual's age at death by counting dental growth lines. Similar to the growth rings of a tree, virtual sections of a tooth reveal incremental growth lines reflecting the body's internal rhythm. Studying the fossilized teeth of the Dikika infant, the team's dental experts calculated an age at death of 2.4 years.

The pace of dental development of the Dikika infant was broadly comparable to that of chimpanzees and therefore faster than in modern humans. But given that the brains of Australopithecus afarensis adults were roughly 20 percent larger than those of chimpanzees, the Dikika child's small endocranial volume suggests a prolonged period of brain development relative to chimpanzees.

"The combination of apelike brain structure and humanlike protracted brain growth in Lucy's species was unexpected, " says Kimbel. "That finding supports the idea that human brain evolution was very much a piecemeal affair, with extended brain growth appearing before the origin of our own genus, Homo . "

Among primates, different rates of growth and maturation are associated with different infant-care strategies, suggesting that the extended period of brain growth in Australopithecus afarensis may have been linked to a long dependence on caregivers. Alternativamente, slow brain growth could also primarily represent a way to spread the energetic requirements of dependent offspring over many years in environments where food is not always abundant. En cualquier caso, protracted brain growth in Australopithecus afarensis provided the basis for subsequent evolution of the brain and social behavior in hominins and was likely critical for the evolution of a long period of childhood learning.