Un arrastrero Brixham del siglo XIX de William Adolphus Knell. Crédito:Museo Marítimo Nacional / Wikipedia

Los barcos británicos fueron superados en número por unos ocho a uno por los franceses. Al poco tiempo hubo colisiones y se lanzaron proyectiles. Los británicos se vieron obligados a retirarse, regresando a puerto con las ventanas rotas pero afortunadamente sin heridos.

El conflicto detrás de esta escaramuza entre pescadores británicos y franceses en la bahía de Seine a fines de agosto de 2018 fue rápidamente apodado en la prensa como la "guerra de las vieiras". Los franceses habían estado tratando de evitar que las dragas de vieiras británicas pesquen legalmente en los lechos en aguas nacionales francesas. Pero el incidente expuso tensiones que han estado hirviendo durante muchos años.

En el marco de la Política Pesquera Común (PPC) de la Unión Europea, los pescadores británicos tenían el derecho legal de pescar en estas aguas, al igual que cualquier barco de un estado miembro de la UE. La complicación vino de una regulación francesa que impedía a los barcos locales pescar en estas aguas entre el 16 de mayo y el 30 de septiembre de cada año. para permitir que las existencias se recuperen de la cosecha anual. Pero bajo la PPC, un país de la UE no tiene autoridad para impedir que la flota de otro estado miembro faene en sus aguas.

Esta peculiaridad de la CFP dejó a los pescadores franceses sin poder dragar vieiras hasta el 1 de octubre. y se vieron obligados a permanecer de pie y observar mientras las flotas de otros países recolectaban lo que veían como un recurso francés en aguas francesas. Cuando llegaron los barcos británicos, los pescadores franceses asumieron el papel de guardianes de sus recursos, acciones que creían que estaban justificadas pero que la industria pesquera británica consideraba ilegales.

Este incidente en un pequeño rincón de un mar compartido de la UE se resolvió en unas pocas semanas gracias a un nuevo acuerdo sobre cómo los dos países compartirían la cosecha de vieiras. Pero las tensiones subyacentes que ha creado la PPC sobre el reparto de los recursos nacionales son mucho más profundas, con la sensación de que las reglas no permiten un uso justo de los mares.

Este sentimiento de injusticia se expresó obviamente en el papel que jugó la pesca en la decisión de Gran Bretaña de abandonar la UE. Los activistas prometieron que "recuperar el control" de las aguas británicas permitiría al país reactivar su industria pesquera en declive y las comunidades que dependen de ella.

Sin embargo, independientemente del impacto que ha tenido la PPC en los pescadores británicos, su futuro después del Brexit depende en gran medida de cualquier acuerdo comercial futuro que el gobierno negocie con la UE. Y la historia de cómo Gran Bretaña ha respondido a los conflictos por los derechos de pesca mucho más grandes que la guerra de las vieiras no augura nada bueno para la industria.

El inicio del declive

La investigación sobre la actividad pesquera muestra que el declive de la industria pesquera británica comenzó mucho antes de la creación de cualquier política pesquera europea. De hecho, sus orígenes últimos se remontan a una fuente sorprendente:la expansión de los ferrocarriles a finales del siglo XIX.

Pesca de arrastre bajo el poder de la vela, había existido durante más de 500 años. Pero sin refrigeración, el pescado solo podía entregarse para la venta en zonas cercanas a los puertos. La llegada de la red ferroviaria significó que el pescado podía transportarse tierra adentro hasta las grandes ciudades y pueblos.

Para satisfacer aún más esta creciente demanda, Los arrastreros de vapor comenzaron a reemplazar a los arrastreros de vela a partir de la década de 1880. La potencia de estos barcos de vapor aumentó enormemente el alcance de la pesca de arrastre y les permitió navegar durante más tiempo y más lejos del puerto mientras remolcaban redes más grandes. Los arrastreros de vapor británicos se aventuraron más lejos de Gran Bretaña en busca de pescado, con los caladeros expandiéndose a áreas tan lejanas como Groenlandia, el norte de Noruega y el mar de Barent, Islandia y las Islas Feroe.

Pero ya en 1885, Se expresó la preocupación de que este avance en la tecnología estuviera teniendo un impacto negativo tanto en las poblaciones de peces como en su hábitat. La evidencia de los registros de la actividad pesquera muestra que esta mejora en la tecnología y el aumento del tamaño de la flota pesquera estuvieron directamente detrás del aumento de los desembarques.

El boom pesquero que habían desatado los ferrocarriles resultó insostenible, y la sobrepesca resultante finalmente enviaría a la industria a una recesión a largo plazo. Después de décadas de pesca cada vez mayor, Los desembarcos finalmente comenzaron a declinar después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, una tendencia que continuó durante la segunda mitad del siglo XX y en el nuevo milenio.

Para compensar, el tamaño y la potencia de la flota siguieron aumentando a medida que se requerían más esfuerzos para capturar peces cada vez más escasos. Desde finales de la década de 1950, la cantidad de pescado desembarcado por unidad de energía disminuyó a un ritmo más rápido que los desembarques de pescado, a medida que la flota siguió dedicando cada vez más esfuerzos a mantener el tamaño de las capturas. Sin embargo, todo este esfuerzo fue en vano y en 1980 las capturas habían disminuido a su punto más bajo en un siglo.

Odinn de Islandia y HMS Scylla se enfrentan en el Atlántico Norte durante la "Tercera Guerra del Bacalao" en la década de 1970. Crédito:Isaac Newton / www.hmsbacchante.co.uk

Guerras de bacalao

La sobrepesca no fue la única razón del declive, sin embargo. La caída de las poblaciones de peces, combinada con las mejoras en el alcance y la potencia de la flota en los años de la posguerra, llevó a los pescadores británicos a buscar nuevas aguas. con más barcos alejándose del Reino Unido para capturar suficiente pescado para satisfacer la demanda interna. Y esta pesca de arrastre de largo alcance puso a la flota del Reino Unido en conflicto con Islandia.

Los pescadores británicos habían pescado en estas aguas desde el siglo XV. Sin embargo, La industria pesquera de Islandia comenzó a resentir esto cuando los arrastreros de vapor comenzaron a pescar en Islandia a fines del siglo XIX. Dio lugar a acusaciones de que los arrastreros británicos estaban dañando los caladeros y agotando las poblaciones. En 1952, Islandia declaró una zona de cuatro millas alrededor de su país para detener la pesca extranjera excesiva, aunque los peces no se adhieren a los límites creados por el hombre y las poblaciones aún podrían agotarse fuera de esta zona. La decisión de Islandia obtuvo una respuesta del Reino Unido, que prohibió la importación de pescado islandés. Como importante mercado de exportación para la industria más importante de Islandia, esperaban que esto los llevara a la mesa de negociaciones.

En 1958, en un contexto de diplomacia fallida, Islandia amplió esta zona a 12 millas y prohibió a las flotas extranjeras pescar en estas aguas. desafiando el derecho internacional. Condujo a la primera de lo que se conoció como las Guerras del Cod, un acto en tres etapas que duró casi 20 años.

Durante la primera Guerra del Bacalao, Las fragatas de la Royal Navy acompañaron a la flota del Reino Unido a la zona de exclusión de Islandia para continuar su pesca. Se produjo un juego del gato y el ratón entre los barcos de la Guardia Costera de Islandia y los arrastreros británicos. En respuesta a los intentos de apoderarse de ellos, los arrastreros embistieron a los guardacostas y los guardacostas amenazaron con abrir fuego, aunque se evitaron incidentes importantes.

En 1961, los dos países finalmente llegaron a un acuerdo que permitió a Islandia mantener su zona de 12 millas. En cambio, al Reino Unido se le concedió acceso condicional a estas aguas.

En 1972, sin embargo, la sobrepesca fuera de este límite había empeorado e Islandia extendió su zona exclusiva a 50 millas y luego, tres años después, a 200 millas. Ambos movimientos provocaron más enfrentamientos entre los arrastreros islandeses y los barcos de escolta de la Royal Navy. respectivamente apodado la segunda y tercera Guerra del Bacalao.

Los buques de la Guardia Costera de Islandia remolcaban dispositivos diseñados para cortar los cables de acero de las redes de arrastre (tenazas) de los arrastreros británicos, y los buques de todos los lados se vieron involucrados en colisiones deliberadas. Aunque estos enfrentamientos fueron principalmente incruentas, a British fisher was seriously injured when he was hit by a severed hawser and an Icelandic engineer died while repairing damage to a trawler that had clashed with a Royal Navy frigate.

In January 1976, British naval frigate HMS Andromeda collided with Thor, an Icelandic gunboat, which also sustained a hole in its hull. While British officials called the collision a "deliberate attack", the Icelandic Coastguard accused the Andomeda of ramming Thor by overtaking and then changing course. Eventually NATO intervened and another agreement was reached in May 1976 over UK access and catch limits. This agreement gave 30 vessels access to Iceland's waters for six months.

NATO's involvement in the dispute had little to do with fisheries and a large amount to do with the Cold War. Iceland was a member of NATO, and therefore aligned to the US, with a substantial US military presence in Iceland at the time. Iceland believed that NATO should intervene in the dispute but it had up until that point resisted. Popular feeling against NATO grew in Iceland and the US became concerned that this strategically important island nation – which allowed control of the Greenland Iceland UK (GIUK) gap, an anti-submarine choke point – could leave NATO and worse, align itself with the Soviets.

Amid protests at the US military base in Iceland demanding the expulsion of the Americans, and growing calls from Icelandic politicians that they should leave NATO, the US put pressure on the British to concede in order to protect the NATO alliance. The agreement brought to an end more than 500 years of unrestricted British fishing in these waters.

The loss of these Atlantic fishing grounds cost 1, 500 jobs in the home ports of the UK's distant water fleet, concentrated around Scotland and the north-east of England, with many more jobs lost in shore-based support industries. This had a significant negative impact on the fishing communities in these areas.

The UK also established its own 200-mile limit in response to Iceland's exclusion zone. These limits were eventually incorporated in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, giving similar rights to every sovereign nation. The creation of these "exclusive economic zones" (EEZ) was the first time that the international community had recognised that nations could own all of the resources that existed within the seas that surrounded them and exclude other nations from exploiting these resources.

The UK now owned the rights to the 200-mile zone around its islands, which contained some of the richest fishing grounds in Europe but up until this point the principle of "open seas" had existed, with Britain its most vocal champion. Fishing nations, had fished the high seas within 200 miles of their own and others coasts for centuries and now were restricted to their own.

British trawler Coventry City passes Icelandic Coastguard patrol vessel Albert off the Westfjords in 1958 during the first Cod War. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia

Economic trade offs

Britain's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), sin embargo, wasn't that exclusive.

On joining the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) in 1972, the UK had agreed to a policy of sharing access to its waters with all member states, and gaining access to the waters of other countries in return. The UN convention effectively gave the EEC one giant EEZ.

The UK government was willing to enter into the agreement as fisheries were one part of overall negotiations that would allow the UK to export goods and services to the European continent with significantly reduced trade barriers.

Although the fishing industry is of high local importance to fishing communities, it is relatively unimportant to the UK economy as a whole. En 2016, the UK fishing industry (which includes the catching sector and all associated industries) was valued at £1.6 billion, against £1.76 trillion for the UK economy as a whole – or just under 1%. The UK's trade with the EU, both import and export, stands at £615 billion a year in comparison.

Enter the Common Fisheries Policy

En 1983, the Common Fisheries Policy was adopted, introducing management of European waters by giving each state a quota for what it could catch, based on a pre-determined percentage of total fishing opportunities. This was known as "relative stability" and was based on each country's historic fishing activity before 1983, which still determines how quotas are allocated today.

The formula that the EEC adopted, based on historic catches, is one of most contentious parts of the CFP for the UK. Many fishers have stories of the years running up to 1983, where foreign vessels increased their fishing activity in UK waters in order to secure a larger share of these fish in perpetuity. Although there is little evidence to support these views, it demonstrates the level of distrust in both the system, and foreign fishers, from the outset.

Como resultado, only 32% of fish caught in the UK EEZ today is caught by UK boats, with most of the remainder taken by vessels from other EU states, Norway and the Faroe Islands (who have also joined the CFP). Por lo tanto, non-UK vessels catch the remaining 68%, about 700, 000 tonnes, of fish a year in the UK EEZ.In return, the UK fleet lands about 92, 000 tonnes a year from other EU countries' waters.

Joining the CFP did not cause a decline in UK fish landings. Sin embargo, in its early days, it did nothing to stop it. Fish landings continued to decline – and along with this, the industry itself contracted, using improved technology to offset the decline in stocks. Through the 1980s and into the early part of this century the imbalance – enshrined in the relative stability measure of the CFP – has led to the view that the CFP doesn't work in the UK's interests. Rather it allows the rest of the EU to take advantage of the country's fish stocks.

The CFP's quota system, while credited for helping the industry survive (and even reverse the collapse in fish stocks), is now seen as burdensome and preventing further growth.

A recent academic analysis of the current performance of the CFP showed it was not improving the management of the fish stock resources in any of its 17 criteria and was actually making things worse in seven areas.

Por ejemplo, a 2013 reform of the CFP introduced the landing obligation, the so-called "discard ban", that was designed to stop vessels discarding fish (bycatch) caught alongside the species they were targeting. Environmentalists, and campaigns backed by celebrities such as Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, have long voiced concerns over incidents of bycatch being dumped by fishers operating under the quota system.

This policy is now seen as potentially disastrous by some representatives of Britain's North Sea fishing fleet, as so many different types of fish live in the waters and bycatch is common and often unavoidable. They are concerned that boats would be forced to fill their holds with commercially worthless fish and return to port early. Or by exhausting their quota for some species early in the season, they would be forced to stay in port for the rest of the year, despite having quotas available for other species. Evidence given to the House of Lords suggests that this situation has not arisen as non-compliance and a lack of enforcement has undermined the discard ban.

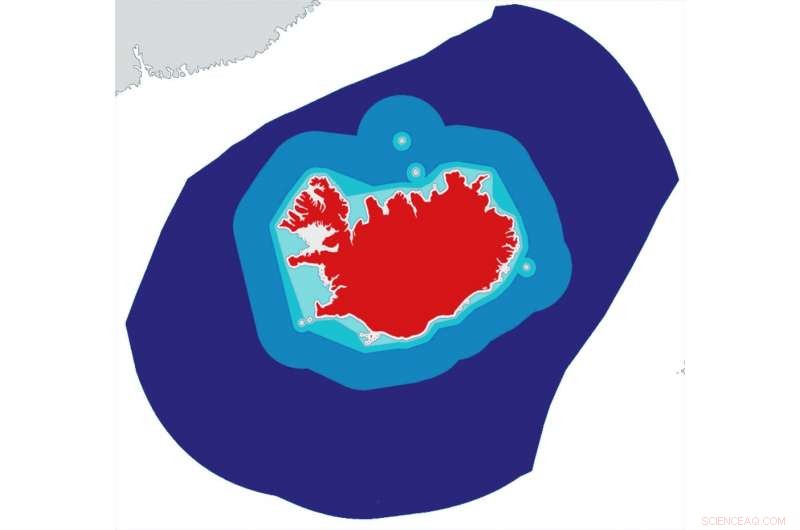

Map of the Icelandic EEZ, and its expansion. Red =Iceland. White =internal waters. Light turquoise =four-mile expansion, 1952. Dark turquoise =12-mile expansion (current extent of territorial waters), 1958. Blue =50-mile expansion, 1972. Dark blue =200-mile expansion (current extent of EEZ), 1975. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

When we interviewed fishers in north-east Scotland in 2018, we found many feared such blanket management across the entire EU would continue to damage their industry because it simply does not take into account the local environment that they work in.

Brexit

The depth of feeling among the UK fishing community was illustrated by the voting figures for the EU referendum in June 2016.

In Banff and Buchan, the constituency in Scotland containing Peterhead and Fraserburgh – the largest and third largest fishing ports in the UK respectively – 54% of people voted to leave the EU, with the size of the fishing industry given as the reason for this result. The result compared to 52% for the whole of the UK and just 38% for Scotland. A survey of members of the UK fishing industry before the vote indicated that 92.8% of correspondents believed that doing so would improve the UK fishing industry by some measure.

But will Brexit really bring the fishing revival so many have promised and hoped for? British politicians have promised a renaissance in UK fishing after leaving the EU. A Fisheries Bill was launched by the environment secretary, Michael Gove, with an aim to "take back control of UK waters". Sin embargo, no definitive plan to remove the UK from the CFP in a transition deal has been made, nor has the industry been given any answers on future access for EU vessels, the apportionment of any new quota – if indeed the quota system remains as it is – the rules that they will be operating under, or even a date on which this will come into effect.

The UK government is seen by many in the fishing industry to be acting against their interests in pursuit of wider goals, for example by using the industry as a bargaining chip in wider UK trade negotiations with the EU.

The fishing industry's distrust of the government has a long tail:many believe they were sacrificed in 1973 by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, in order to secure access to the single market.

A soured relationship

Irónicamente, despite the fishing industry's support for Brexit and the popular campaign promises, our research suggests fishers don't simply want to close British waters to European fleets. We interviewed people who were sympathetic to their fellow fishers from abroad and did not wish to see businesses and livelihoods lost. They favour a re-balancing of quotas over time to allow EU vessels to adapt to the change, with all vessels having to adhere to UK rules. This would avoid any situations similar to the Scallop War by ensuring that all vessels with a quota have to abide by local restrictions.

The EU is the main export market for UK fish and fisheries products accounting for 70% of UK fisheries exports by value. Valued at £1.3 billion, this trade far exceeds the £980m value of fish landed in the UK, due to the added value from the processing sector. Some of the remaining 30% of exports that go to countries outside of the EU are governed by trade agreements negotiated by the EU that reduce trade barriers. So the single market, and additional trade agreements, are crucial to the success of the UK fishing industry.

This reliance on trade into the EU puts the industry in a position where unilaterally preventing access to UK waters would likely be met by reciprocal trade barriers and tariffs. This would increase the cost of their product, while reducing access to their biggest market. The question for the government, luego, is how to balance a political issue against an economic one?

The issue centres on the word "control". If the UK has control of its waters that would simply mean that its government has the power to decide on anything from keeping fishing within UK waters purely for UK vessels, to remaining in or re-entering the CFP, or all points in between. Until the deals are negotiated and signed, the industry will remain in a limbo that has reopened old wounds and reignited distrust in the UK government.

Este artículo se ha vuelto a publicar de The Conversation con una licencia de Creative Commons. Lea el artículo original.