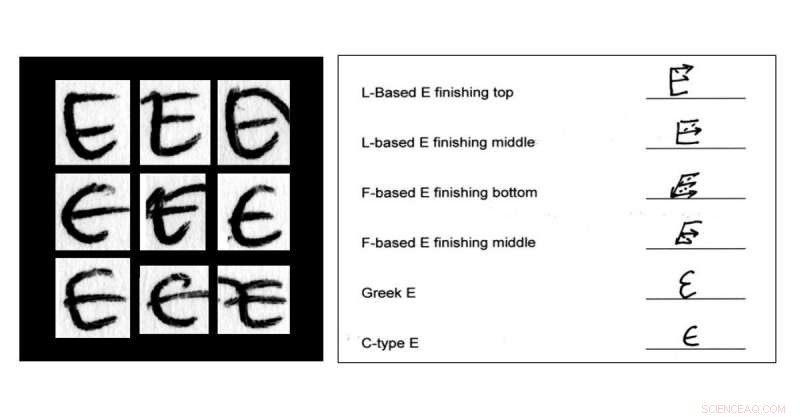

Un rango de variación natural en la letra mayúscula "E" de un escritor Crédito:NIST

La gente escribe más que nunca con sus teclados y teléfonos, pero las notas escritas a mano se han vuelto raras. Incluso las firmas están pasando de moda. La mayoría de las compras con tarjeta de crédito ya no las requieren, y si lo hacen por lo general, puede rascar uno con la uña. El antiguo arte de la escritura a mano está en declive.

Esto marca un cambio profundo en la forma en que nos comunicamos, pero para un grupo de expertos también plantea una cuestión existencial. Los examinadores forenses de escritura a mano autentican las notas y firmas escritas a mano, o revelan que son falsas, analizando las características distintivas de nuestra escritura. Como la gente escribe menos a mano, ¿Se volverá irrelevante el examen de escritura a mano?

Un informe reciente del Instituto Nacional de Estándares y Tecnología (NIST) sugiere que la respuesta es no, si el campo cambia para mantenerse al día. Pero los tiempos están cambiando en más de un sentido, y el declive de la escritura a mano es sólo uno de los desafíos que tendrá que afrontar el campo.

Cómo lo hacen los expertos

Emily Will es una examinadora de escritura a mano certificada por la junta en la práctica privada en Carolina del Norte. Ella ha examinado firmas en innumerables cheques, testamentos escrituras y fideicomisos. Ha inspeccionado los registros médicos para evaluar si se pudo haber agregado la firma de un médico en una fecha posterior a la indicada. quizás después de que se entablara una demanda. También ha examinado formas más largas de escritura, como cartas de amenaza o acoso y notas de suicidio. Si la aparente víctima de suicidio no escribió la nota, la policía podría tener un homicidio entre manos.

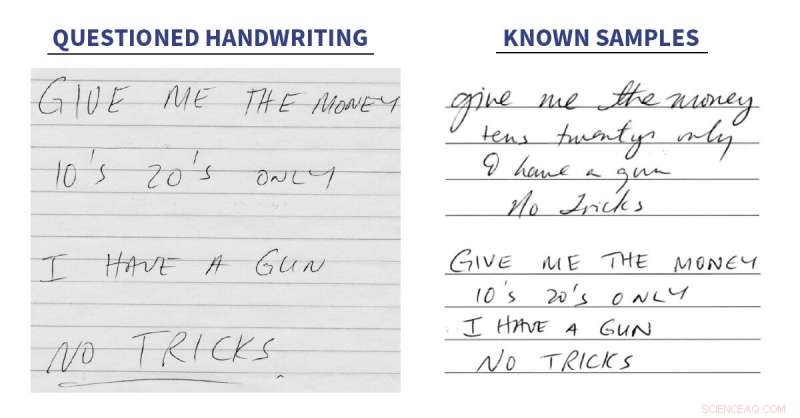

Para evaluar si una escritura a mano fue escrita por una persona en particular, los examinadores necesitan algo con lo que compararlo, por lo que recopilan muestras de escritura que se sabe que son de esa persona. El tipo de escritura tiene que ser el mismo, si una firma, escritura cursiva, o impresión a mano. Las muestras conocidas deben ser aproximadamente del mismo período de tiempo que la escritura en cuestión, porque nuestra escritura a mano evoluciona con el tiempo. Y tener varias muestras conocidas para comparar es clave, ya que eso permitirá al examinador considerar la variabilidad en el estilo de escritura de una persona.

"No eres un robot, así que cada vez que firmes tu nombre, se verá diferente, "Dijo Will." Eso es lo que hace que el examen de escritura a mano sea tan interesante ".

Las personas no profesionales podrían pensar que, dado que la mayoría de las personas saben cómo escribir a mano, prácticamente cualquiera puede examinarlo. Pueden asumir que el experto compara cosas como el tamaño, inclinación y espaciado de las letras y las conexiones entre ellas. En efecto, los examinadores hacen eso. Pero también miran más allá de esas características de la escritura en busca de signos más sutiles de cómo se hizo la escritura.

"Di que quieres falsificar una firma, "Will dijo." Es posible que pueda ejecutar un buen facsímil. ¿Pero es el "O 'en el sentido de las agujas del reloj cuando debería estar en el sentido contrario a las agujas del reloj? ¿Hay elevadores de bolígrafos donde no debería haberlos? Cuando firmas con tu nombre, todo es memoria muscular. Pero forjar una firma requiere deliberación. El bolígrafo se ralentiza. Se detiene y comienza . " Esas vacilaciones aparecen bajo un microscopio como pequeños charcos de tinta.

"No se trata tanto de cómo se ve la firma, pero cómo se ejecutó eso es importante, "Dijo Will.

Esto es lo que Will lleva en su bolsa de viaje:una lupa de joyero, un pequeño microscopio óptico y un microscopio digital de mano. Una linterna. Un micrómetro de papel, para medir el grosor del papel. Una computadora portátil y un escáner portátil. Una cámara que se conecta a sus microscopios. "Y francamente, " ella dice, "Utilizo mucho mi iPhone estos días".

La práctica de Will se extiende al campo más amplio del "examen de documentos cuestionados, "que implica examinar un documento completo en busca de signos de fraude. En su laboratorio, dispone de equipos para analizar papeles y tintas y visualizarlos bajo diferentes tipos de luz. Algunas tintas que se ven idénticas a la luz del día parecen marcadamente diferentes bajo el infrarrojo. Ella identifica tachaduras, alteraciones y obliteraciones y revela escritura con sangría:las impresiones dejadas en hojas de papel debajo de la nota escrita.

Pero la mayor parte del trabajo de Will incluye escritura a mano y firmas, y hay muchos menos en estos días. El fraude en el cambio de cheques ha disminuido ahora que los cheques de pago y los cheques del Seguro Social se depositan directamente. Las demandas por negligencia médica involucran menos firmas ya que los registros de salud electrónicos se han convertido en la norma. Incluso las celebridades han notado el cambio. In a 2014 opinion article in The Wall Street Journal, Taylor Swift wrote, "I haven't been asked for an autograph since the invention of the iPhone with a front-facing camera."

Enough handwriting still passes under Will's microscope to keep her in business. Pero, ella dice, "If I were a young person starting out today, I might consider cybersecurity."

Forensic handwriting examiners can only compare writing of the same type. En este caso, only the second known sample can be compared to the questioned handwriting. Credit:NIST

A Roadmap for Staying Relevant

The field of forensic handwriting examination may have trouble attracting new blood. A report from NIST earlier this year found that the median age for handwriting examiners is 60, compared with 42 to 44 for people in similar scientific and technical occupations. Ese informe, Forensic Handwriting Examination and Human Factors:Improving the Practice Through a Systems Approach, was published by NIST, but was written by 23 outside experts, including Will.

To increase recruitment, the report recommends replacing the unpaid apprenticeships that have been the traditional route of entry into the field with grants and fellowships. The report also recommends cross-training with other forensic disciplines that involve pattern matching, such as fingerprint examination.

The "human factors" in the report's title refers to a field of study that seeks to understand the factors that affect human capability and job performance. In forensic science, these include training, comunicación, technology and management policies, por nombrar unos cuantos.

Melissa Taylor, the NIST human factors expert who led the group of authors, said that the report provides the forensic handwriting community with a road map for staying relevant. But the threat of irrelevance doesn't come only from the decline in handwriting. Part of the challenge, ella dice, arises from the field of forensic science itself.

"There is a big push toward greater reliability and more rigorous research in forensic science, "dijo Taylor, whose research is aimed at reducing errors and improving job performance in handwriting examination and other forensic disciplines, including fingerprints and DNA. "To stay relevant, the field of handwriting examination will have to change with the times."

Among other changes, the report recommends more research to estimate error rates for the field. This will allow juries and others to consider the potential for error when weighing an examiner's testimony. The report also recommends that experts avoid testifying in absolute terms or saying that an individual has written something to the exclusion of all other writers. En lugar de, experts should report their findings in terms of relative probabilities and degrees of certainty.

These recommendations are consistent with findings in a landmark 2009 report from the National Academy of Sciences. Called Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States:A Path Forward, that report said that "there may be a scientific basis for handwriting comparison, " but that there has been only limited research on its reliability.

Knowing When to Not Make a Call

Children used to learn handwriting in school by copying letters and phrases from books that contained models of ideal penmanship. Different copybooks had different styles, and an expert could often tell from a person's handwriting whether they were trained in the Palmer style, the Spencer style, or something else. By identifying a specific copybook style, an examiner could quickly narrow the range of potential writers.

Many children no longer learn cursive writing in school, and whether this helps or hinders handwriting examination is unknown. "It might actually make handwriting more identifiable because it allows people to develop their own individual styles of writing, " said Linton Mohammed, author of the widely used textbook Forensic Examination of Signatures, and a co-author of the NIST-led study.

Por otra parte, it might make the task harder by depriving experts of a system for classifying writing styles. This is one reason why research on error rates is needed. The way people learn to write has changed, and error-rate studies can show whether handwriting examiners are successfully adapting to those changes. "We claim to be good at this, " Mohammed said. "But how good are we really?"

Several studies have attempted to answer this question by testing whether experts are more competent at handwriting examination than people with no training. The results reveal a great deal about both handwriting examination and human psychology.

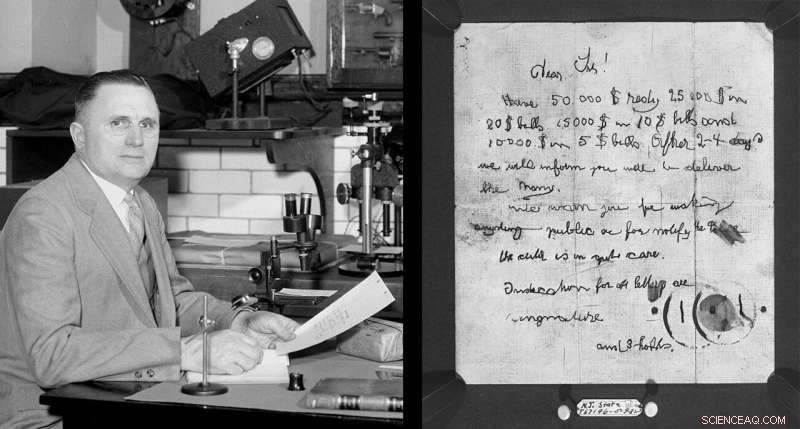

In the 1930s, a physicist at NIST, then known as the National Bureau of Standards, became a leading handwriting expert. His name was Wilmer Souder, and the most famous case he worked on was 1932 the kidnapping of Charles Lindberg Jr., the infant son of the famous aviator. Despite the notoriety of this case, Souder himself kept an extremely low profile — so much so that when he retired, a profile in "Reader's Digest" referred to him as Detective X. Credit:NBS/NIST; source:NARA

In many of these studies, participants are shown pairs of signatures and asked to determine whether they are both by the same person or if one is a fake. Calculating overall error rates from multiple studies is difficult due to differences in study design. But consistently, across studies, both experts and novices made roughly the same proportion of correct decisions, according to a 2018 metastudy led by Alice Towler at the University of New South Wales, Australia. The novices, sin embargo, made a much higher proportion of errors, while the experts more frequently declined to make a call. If a signature lacked complexity or was otherwise difficult to compare, the experts would more readily find the evidence inconclusive. This ability to defer judgment is critical to reducing errors in forensic science.

The tendency of novices to rush to judgment in cases where experts defer reflects a quirk of human psychology. People with limited knowledge or expertise in a subject often overestimate their own competence. This is called the Dunning-Kruger effect, for the psychologists who first described it. In the case of handwriting, people might be particularly susceptible. Después de todo, pretty much anyone can produce handwriting. How hard can it be to examine?

But error rate studies show that at least some experts recognize their limitations when faced with a difficult task. "I've been doing this for 30-plus years, and I realized early on that there's a lot that we don't know, " Mohammed said. "So we have to be very careful in reaching our conclusions."

The End of Handwriting Examination, or a New Beginning?

Like Emily Will, Mohammed has examined many wills, deeds and trusts. He has also analyzed ransom notes, threatening letters, and one hit list. Being based in the San Francisco Bay Area, where the tech boom has minted many fortunes, he has also examined many stock-option grants and prenuptial agreements.

Although Mohammed started his career with the San Diego County Sheriff's Department, today he is in private practice. In his current home base of northern California, he says, there are no government laboratories that still examine questioned documents. This reflects a nationwide trend—a report from the Department of Justice found that only 14% of publicly funded crime labs did their own questioned document examinations in 2014, down from 24% in 2002.

Those numbers may mean that the field is consolidating rather than disappearing. If smaller labs can no longer support in-house experts due to a diminishing caseload, they can farm out work to private sector experts like Will and Mohammed. Al mismo tiempo, larger federal labs, including the FBI Laboratory and the U.S. Army's Defense Forensic Science Center, continue to maintain questioned document units. This is in part because their focus includes international terrorism, where handwritten documents are still a source of valuable intelligence, and in part because the United States is a big place. A escala nacional, crimes involving handwriting still occur frequently enough that federal labs need to keep experts on staff.

When asked if handwriting examiners will soon become irrelevant, one federal expert said that as long as greed and fraud exist, there will be a need for handwriting examiners.

When asked the same question, Mohammed noted that changing technology did not doom the field in the past. "When the ballpoint pen came out, people said, "That's the end of handwriting examination, '" he said. People mostly stopped using fountain pens, but handwriting examination survived the transition.

Melissa Taylor, the NIST expert, agrees that handwriting examination is still a needed skill and will remain relevant—if the field successfully adapts to changing expectations around research and reliability. And if the new report, which counts many leading handwriting experts among its authors, is any indication, the needed changes may already be underway.

"There will still be documents. There will still be signatures, " Taylor said. "And most people don't print stickup notes on their laser printer. They scribble them on the dashboard before running into the bank."

Some things will never change.