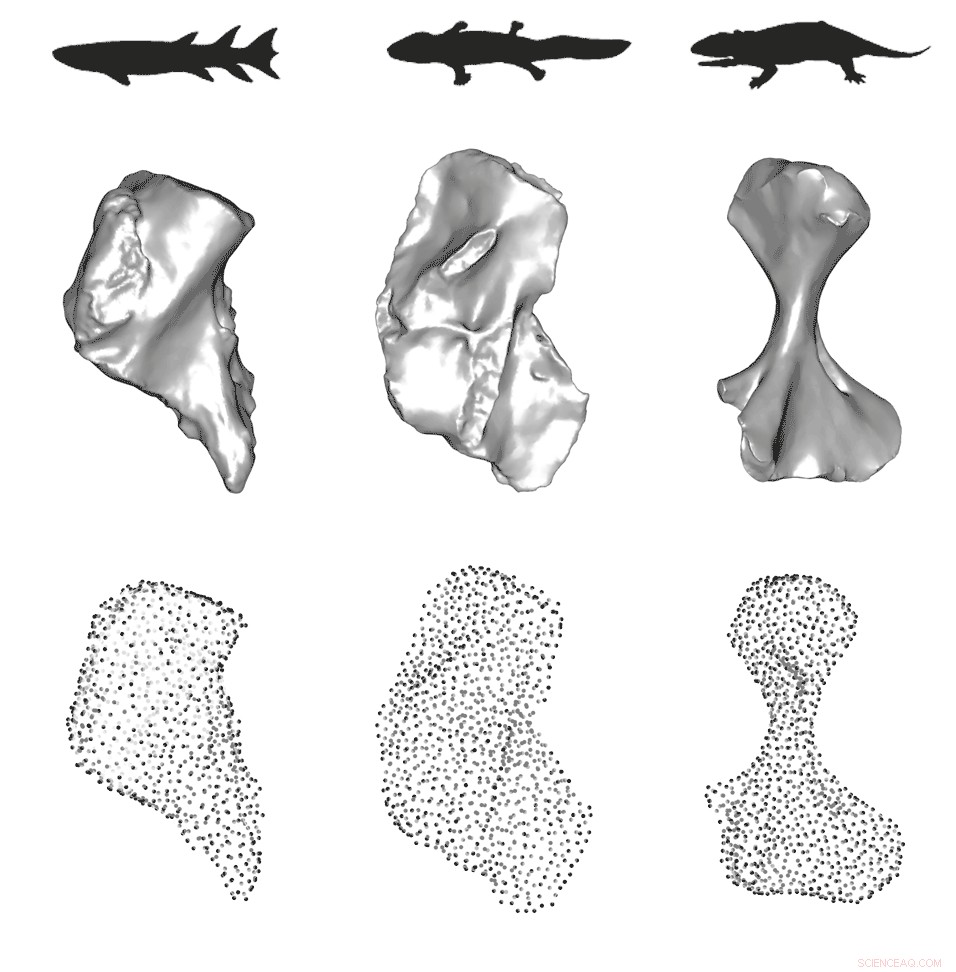

Tres etapas principales de la evolución de la forma del húmero:desde el húmero en bloques de los peces acuáticos, al húmero en forma de L de los tetrápodos de transición, y el húmero retorcido de los tetrápodos terrestres. Columnas (de izquierda a derecha) =pez acuático, tetrápodo de transición, y tetrápodos terrestres. Filas =Arriba:siluetas de animales extintos; Medio:fósiles de húmero 3D; Abajo:puntos de referencia utilizados para cuantificar la forma. Crédito:Blake Dickson

La transición de agua a tierra es una de las transiciones más importantes e inspiradoras en la evolución de los vertebrados. Y la cuestión de cómo y cuándo los tetrápodos pasaron del agua a la tierra ha sido durante mucho tiempo una fuente de asombro y debate científico.

Las primeras ideas postulaban que los charcos de agua que se secaban dejaban a los peces varados en la tierra y que estar fuera del agua proporcionaba la presión selectiva para desarrollar más apéndices en forma de extremidades para caminar de regreso al agua. En la década de 1990, los especímenes recién descubiertos sugirieron que los primeros tetrápodos conservaban muchas características acuáticas, como branquias y aleta caudal, y que las extremidades pueden haber evolucionado en el agua antes de que los tetrápodos se adaptaran a la vida en la tierra. Hay, sin embargo, Todavía hay incertidumbre sobre cuándo tuvo lugar la transición de agua a tierra y cómo eran realmente los primeros tetrápodos terrestres.

Un artículo publicado el 25 de noviembre en Naturaleza aborda estas preguntas utilizando datos fósiles de alta resolución y muestra que, aunque estos primeros tetrápodos todavía estaban atados al agua y tenían características acuáticas, también tenían adaptaciones que indican cierta capacidad para moverse en tierra. A pesar de que, puede que no hayan sido muy buenos haciéndolo, al menos según los estándares actuales.

Autor principal Blake Dickson, Doctor. '20 en el Departamento de Biología Organísmica y Evolutiva de la Universidad de Harvard, y la autora principal Stephanie Pierce, Thomas D. Cabot Profesor asociado en el Departamento de Biología Organísmica y Evolutiva y curador de paleontología de vertebrados en el Museo de Zoología Comparada de la Universidad de Harvard, examinó 40 modelos tridimensionales de humeri fósiles (hueso de la parte superior del brazo) de animales extintos que unen la transición de agua a tierra.

"Debido a que el registro fósil de la transición a la tierra en los tetrápodos es tan pobre, fuimos a una fuente de fósiles que podría representar mejor la totalidad de la transición desde ser un pez completamente acuático hasta un tetrápodo completamente terrestre, "dijo Dickson.

Dos tercios de los fósiles provienen de las colecciones históricas que se encuentran en el Museo de Zoología Comparada de Harvard, que provienen de todo el mundo. Para llenar los huecos que faltan, Pierce se acercó a sus colegas con especímenes clave de Canadá, Escocia, y Australia. De importancia para el estudio fueron los nuevos fósiles descubiertos recientemente por los coautores, el Dr. Tim Smithson y la profesora Jennifer Clack, Universidad de Cambridge, REINO UNIDO, como parte del proyecto TW:eed, una iniciativa diseñada para comprender la evolución temprana de los tetrápodos terrestres.

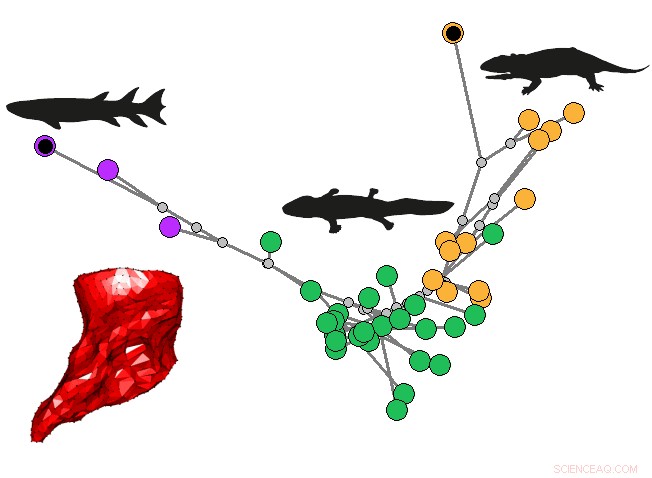

La vía evolutiva y la forma cambian de un húmero de pez acuático a un húmero de tetrápodo terrestre. Crédito:Blake Dickson.

Los investigadores eligieron el húmero porque no solo es abundante y está bien conservado en el registro fósil, pero también está presente en todos los sarcopterigios, un grupo de animales que incluye peces celacanto, pez pulmonado y todos los tetrápodos, incluidos todos sus representantes fósiles. "Esperábamos que el húmero transmitiera una fuerte señal funcional a medida que los animales pasaban de ser un pez completamente funcional a ser tetrápodos completamente terrestres". y que podríamos usar eso para predecir cuándo los tetrápodos comenzaron a moverse por tierra, ", dijo Pierce." Encontramos que la habilidad terrestre parece coincidir con el origen de las extremidades, lo cual es realmente emocionante ".

El húmero ancla la pierna delantera al cuerpo, alberga muchos músculos, y debe resistir mucho estrés durante el movimiento de las extremidades. Debido a esto, contiene una gran cantidad de información funcional crítica relacionada con el movimiento y la ecología de un animal. Los investigadores han sugerido que los cambios evolutivos en la forma del hueso del húmero, from short and squat in fish to more elongate and featured in tetrapods, had important functional implications related to the transition to land locomotion. This idea has rarely been investigated from a quantitative perspective—that is, hasta ahora.

When Dickson was a second-year graduate student, he became fascinated with applying the theory of quantitative trait modeling to understanding functional evolution, a technique pioneered in a 2016 study led by a team of paleontologists and co-authored by Pierce. Central to quantitative trait modeling is paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson's 1944 concept of the adaptive landscape, a rugged three-dimensional surface with peaks and valleys, like a mountain range. On this landscape, increasing height represents better functional performance and adaptive fitness, and over time it is expected that natural selection will drive populations uphill towards an adaptive peak.

Dickson and Pierce thought they could use this approach to model the tetrapod transition from water to land. They hypothesized that as the humerus changed shape, the adaptive landscape would change too. Por ejemplo, fish would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for swimming and terrestrial tetrapods would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for walking on land. "We could then use these landscapes to see if the humerus shape of earlier tetrapods was better adapted for performing in water or on land" said Pierce.

"We started to think about what functional traits would be important to glean from the humerus, " said Dickson. "Which wasn't an easy task as fish fins are very different from tetrapod limbs." In the end, they narrowed their focus on six traits that could be reliably measured on all of the fossils including simple measurements like the relative length of the bone as a proxy for stride length and more sophisticated analyses that simulated mechanical stress under different weight bearing scenarios to estimate humerus strength.

"If you have an equal representation of all the functional traits you can map out how the performance changes as you go from one adaptive peak to another, " Dickson explained. Using computational optimization the team was able to reveal the exact combination of functional traits that maximized performance for aquatic fish, terrestrial tetrapods, and the earliest tetrapods. Their results showed that the earliest tetrapods had a unique combination of functional traits, but did not conform to their own adaptive peak.

"What we found was that the humeri of the earliest tetrapods clustered at the base of the terrestrial landscape, " said Pierce. "indicating increasing performance for moving on land. But these animals had only evolved a limited set of functional traits for effective terrestrial walking."

The researchers suggest that the ability to move on land may have been limited due to selection on other traits, like feeding in water, that tied early tetrapods to their ancestral aquatic habitat. Once tetrapods broke free of this constraint, the humerus was free to evolve morphologies and functions that enhanced limb-based locomotion and the eventual invasion of terrestrial ecosystems

"Our study provides the first quantitative, high-resolution insight into the evolution of terrestrial locomotion across the water-land transition, " said Dickson. "It also provides a prediction of when and how [the transition] happened and what functions were important in the transition, at least in the humerus."

"Avanzando, we are interested in extending our research to other parts of the tetrapod skeleton, " Pierce said. "For instance, it has been suggested that the forelimbs became terrestrially capable before the hindlimbs and our novel methodology can be used to help test that hypothesis."

Dickson recently started as a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Animal Locomotion lab at Duke University, but continues to collaborate with Pierce and her lab members on further studies involving the use of these methods on other parts of the skeleton and fossil record.