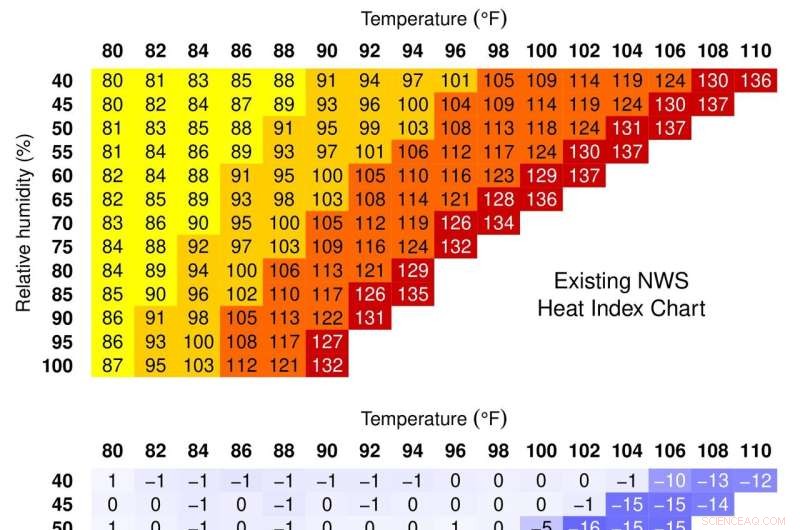

La tabla de índice de calor utilizada durante mucho tiempo (arriba) subestima la temperatura aparente para las condiciones de calor y humedad más extremas que ocurren hoy (centro). La versión corregida (abajo) es precisa en todo el rango de temperaturas y humedades que los humanos encontrarán con el cambio climático. Crédito:David Romps y Yi-Chuan Lu, UC Berkeley

Si observaste el índice de calor durante las olas de calor pegajoso de este verano y pensaste:"Seguro que hace más calor", es posible que tengas razón.

Un análisis realizado por climatólogos de la Universidad de California, Berkeley, encuentra que la temperatura aparente, o índice de calor, calculado por los meteorólogos y el Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (NWS) para indicar qué tan caliente se siente, teniendo en cuenta la humedad, subestima la temperatura percibida. temperatura para los días más sofocantes que ahora estamos experimentando, a veces por más de 20 grados Fahrenheit.

El hallazgo tiene implicaciones para quienes sufren estas olas de calor, ya que el índice de calor es una medida de cómo el cuerpo lidia con el calor cuando la humedad es alta y la sudoración se vuelve menos efectiva para refrescarnos. La sudoración y el enrojecimiento, donde la sangre se desvía a los capilares cercanos a la piel para disipar el calor, y quitarse la ropa son las principales formas en que los humanos se adaptan a las altas temperaturas.

Un índice de calor más alto significa que el cuerpo humano está más estresado durante estas olas de calor de lo que los funcionarios de salud pública pueden darse cuenta, dicen los investigadores. El NWS actualmente considera que un índice de calor por encima de 103 es peligroso y por encima de 125 es extremadamente peligroso.

"La mayoría de las veces, el índice de calor que el Servicio Meteorológico Nacional te da es el valor correcto. Solo en estos casos extremos obtienen el número equivocado", dijo David Romps, profesor de ciencias terrestres y planetarias de UC Berkeley. Ciencias. "Lo que importa es cuando comienzas a mapear el índice de calor de nuevo en los estados fisiológicos y te das cuenta, oh, estas personas están siendo estresadas a una condición de flujo sanguíneo de la piel muy elevado donde el cuerpo está a punto de quedarse sin trucos para compensar para este tipo de calor y humedad. Por lo tanto, estamos más cerca de ese límite de lo que pensábamos antes".

Romps y el estudiante graduado Yi-Chuan Lu detallaron su análisis en un artículo aceptado por la revista Environmental Research Letters y publicado en línea el 12 de agosto.

El índice de calor fue ideado en 1979 por un físico textil, Robert Steadman, quien creó ecuaciones simples para calcular lo que llamó el "bochorno" relativo de las condiciones cálidas y húmedas, así como calurosas y áridas, durante el verano. Lo vio como un complemento del factor de sensación térmica comúnmente utilizado en el invierno para estimar qué tan frío se siente.

Su modelo tuvo en cuenta cómo los humanos regulan su temperatura interna para lograr el confort térmico bajo diferentes condiciones externas de temperatura y humedad, cambiando conscientemente el grosor de la ropa o ajustando inconscientemente la respiración, la transpiración y el flujo sanguíneo desde el centro del cuerpo hasta la piel.

En su modelo, la temperatura aparente en condiciones ideales (una persona de tamaño promedio a la sombra con agua ilimitada) es el calor que sentiría alguien si la humedad relativa estuviera en un nivel cómodo, que Steadman interpretó como una presión de vapor de 1600 pascales. .

For example, at 70% relative humidity and 68 F—which is often taken as average humidity and temperature—a person would feel like it's 68 F. But at the same humidity and 86 F, it would feel like 94 F.

The heat index has since been adopted widely in the United States, including by the NWS, as a useful indicator of people's comfort. But Steadman left the index undefined for many conditions that are now becoming increasingly common. For example, for a relative humidity of 80%, the heat index is not defined for temperatures above 88 F or below 59 F. Today, temperatures routinely rise above 90 F for weeks at a time in some areas, including the Midwest and Southeast.

To account for these gaps in Steadman's chart, meteorologists extrapolated into these areas to get numbers, Romps said, that are correct most of the time, but not based on any understanding of human physiology.

"There's no scientific basis for these numbers," Romps said.

He and Lu set out to extend Steadman's work so that the heat index is accurate at all temperatures and all humidities between zero and 100%.

"The original table had a very short range of temperature and humidity and then a blank region where Steadman said the human model failed," Lu said. "Steadman had the right physics. Our aim was to extend it to all temperatures so that we have a more accurate formula."

One condition under which Steadman's model breaks down is when people perspire so much that sweat pools on the skin. At that point, his model incorrectly had the relative humidity at the skin surface exceeding 100%, which is physically impossible.

"It was at that point where this model seems to break, but it's just the model telling him, hey, let sweat drip off the skin. That's all it was," Romps said. "Just let the sweat drop off the skin."

That and a few other tweaks to Steadman's equations yielded an extended heat index that agrees with the old heat index 99.99% of the time, Romps said, but also accurately represents the apparent temperature for regimes outside those Steadman originally calculated. When he originally published his apparent temperature scale, he considered these regimes too rare to worry about, but high temperatures and humidities are becoming increasingly common because of climate change.

Romps and Lu had published the revised heat index equation earlier this year. In the most recent paper, they apply the extended heat index to the top 100 heat waves that occurred between 1984 and 2020. The researchers find mostly minor disagreements with what the NWS reported at the time, but also some extreme situations where the NWS heat index was way off.

One surprise was that seven of the 10 most physiologically stressful heat waves over that time period were in the Midwest—mostly in Illinois, Iowa and Missouri—not the Southeast, as meteorologists assumed. The largest discrepancies between the NWS heat index and the extended heat index were seen in a wide swath, from the Great Lakes south to Louisiana.

During the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago, for example, which killed at least 465 people, the maximum heat index reported by the NWS was 135 F, when it actually felt like 154 F. The revised heat index at Midway Airport, 141 F, implies that people in the shade would have experienced blood flow to the skin that was 170% above normal. The heat index reported at the time, 124 F, implied only a 90% increase in skin blood flow. At some places during the heat wave, the extended heat index implies that people would have experienced an increase of 820% above normal skin blood flow.

"I'm no physiologist, but a lot of things happen to the body when it gets really hot," Romps said. "Diverting blood to the skin stresses the system because you're pulling blood that would otherwise be sent to internal organs and sending it to the skin to try to bring up the skin's temperature. The approximate calculation used by the NWS, and widely adopted, inadvertently downplays the health risks of severe heat waves."

Physiologically, the body starts going haywire when the skin temperature rises to equal the body's core temperature, typically taken as 98.6 F. After that, the core temperature begins to increase. The maximum sustainable core temperature is thought to be 107 F—the threshold for heat death. For the healthiest of individuals, that threshold is reached at a heat index of 200 F.

Luckily, humidity tends to decrease as temperature increases, so Earth is unlikely to reach those conditions in the next few decades. Less extreme—though still deadly—conditions are nevertheless becoming common around the globe.

"A 200 F heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable," Romps said. "But now that we've got this model of human thermoregulation that works out at these conditions, what does it actually mean for the future habitability of the United States and the planet as a whole? There are some frightening things we are looking at." Hot and getting hotter:Five essential reads on high temps and human bodies