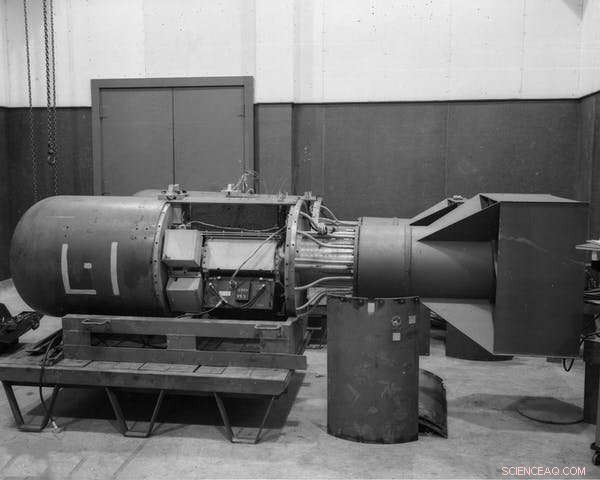

La bomba atómica con nombre en código "Little Boy", del mismo tipo que luego se lanzó sobre Hiroshima, en el Laboratorio Nacional de Los Álamos en 1944. Crédito:Shutterstock

En menos de 24 horas el Boletín de los Científicos Atómicos actualizará el Reloj del Juicio Final. Actualmente faltan 100 segundos para la medianoche, el tiempo metafórico en el que la raza humana podría destruir el mundo con tecnologías de su propia creación.

Las manecillas nunca antes habían estado tan cerca de la medianoche. Hay pocas esperanzas de que regrese a lo que será su 75 aniversario.

Únase a nosotros para el anuncio del 75.° aniversario del Reloj del Juicio Final el jueves 20 de enero a las 10:00 a. m. EST

Detalles:https://t.co/UgE8wtUvND pic.twitter.com/RyWu91AnfP

— Boletín de los científicos atómicos (@BulletinAtomic) 9 de enero de 2022

El reloj se ideó originalmente como una forma de llamar la atención sobre una conflagración nuclear. Pero los científicos que fundaron el Boletín en 1945 estaban menos centrados en el uso inicial de "la bomba" que en la irracionalidad de almacenar armas en aras de la hegemonía nuclear.

Se dieron cuenta de que más bombas no aumentaban las posibilidades de ganar una guerra ni de hacer que nadie estuviera a salvo cuando una sola bomba sería suficiente para destruir Nueva York.

Si bien la aniquilación nuclear sigue siendo la amenaza existencial más probable y aguda para la humanidad, ahora es solo una de las catástrofes potenciales que mide el Reloj del Juicio Final. Como dice el Boletín:"El reloj se ha convertido en un indicador universalmente reconocido de la vulnerabilidad del mundo a las catástrofes provocadas por las armas nucleares, el cambio climático y las tecnologías disruptivas en otros dominios".

Múltiples amenazas conectadas

A nivel personal, siento cierta afinidad académica con los relojeros. Mis mentores, en particular Aaron Novick, y otros que influyeron profundamente en cómo veo mi propia disciplina científica y mi enfoque de la ciencia, se encontraban entre los que formaron y se unieron al Boletín inicial.

En 2022, su advertencia se extiende más allá de las armas de destrucción masiva para incluir otras tecnologías que concentran peligros potencialmente existenciales, incluido el cambio climático y sus causas fundamentales en el consumo excesivo y la riqueza extrema.

Muchas de estas amenazas ya son bien conocidas. Por ejemplo, el uso comercial de productos químicos es omnipresente, al igual que los desechos tóxicos que genera. Hay decenas de miles de sitios de desechos a gran escala solo en los EE. UU., con 1700 "sitios de superfondo" peligrosos priorizados para la limpieza.

Como demostró el huracán Harvey cuando azotó el área de Houston en 2017, estos sitios son extremadamente vulnerables. An estimated two million kilograms of airborne contaminants above regulatory limits were released, 14 toxic waste sites were flooded or damaged, and dioxins were found in a major river at levels over 200 times higher than recommended maximum concentrations.

That was just one major metropolitan area. With increasing storm severity due to climate change, the risks to toxic waste sites grow.

At the same time, the Bulletin has increasingly turned its attention to the rise of artificial intelligence, autonomous weaponry, and mechanical and biological robotics.

The movie clichés of cyborgs and "killer robots" tend to disguise the true risks. For example, gene drives are an early example of biological robotics already in development. Genome editing tools are used to create gene drive systems that spread through normal pathways of reproduction but are designed to destroy other genes or offspring of a particular sex.

Climate change and affluence

As well as being an existential threat in its own right, climate change is connected to the risks posed by these other technologies.

Both genetically engineered viruses and gene drives, for example, are being developed to stop the spread of infectious diseases carried by mosquitoes, whose habitats spread on a warming planet.

Once released, however, such biological "robots" may evolve capabilities beyond our ability to control them. Even a few misadventures that reduce biodiversity could provoke social collapse and conflict.

Similarly, it's possible to imagine the effects of climate change causing concentrated chemical waste to escape confinement. Meanwhile, highly dispersed toxic chemicals can be concentrated by storms, picked up by floodwaters and distributed into rivers and estuaries.

The result could be the despoiling of agricultural land and fresh water sources, displacing populations and creating "chemical refugees."

Resetting the clock

Given that the Doomsday Clock has been ticking for 75 years, with myriad other environmental warnings from scientists in that time, what of humanity's ability to imagine and strive for a different future?

Part of the problem lies in the role of science itself. While it helps us understand the risks of technological progress, it also drives that process in the first place. And scientists are people, too—part of the same cultural and political processes that influence everyone.

J. Robert Oppenheimer—the "father of the atomic bomb"—described this vulnerability of scientists to manipulation, and to their own naivete, ambition and greed, in 1947:"In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose."

If the bomb was how physicists came to know sin, then perhaps those other existential threats that are the product of our addiction to technology and consumption are how others come to know it, too.

Ultimately, the interrelated nature of these threats is what the Doomsday Clock exists to remind us of.