Este 12 de septiembre La foto de 2019 muestra un coral blanqueante en la bahía de Kahala'u en Kailua-Kona, Hawai. Solo cuatro años después de que una gran ola de calor marina mató a casi la mitad de los corales de esta costa, Los investigadores federales predicen que otra ronda de agua caliente provocará una de las peores decoloraciones de corales que jamás haya visto la región. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

En el borde de un antiguo flujo de lava donde las rocas negras dentadas se encuentran con el Pacífico, pequeñas casas fuera de la red tienen vista a las tranquilas aguas azules de Papa Bay en la Isla Grande de Hawái, sin turistas ni hoteles a la vista. Aquí, uno de los arrecifes de coral más abundantes y vibrantes de las islas prospera justo debajo de la superficie.

Sin embargo, incluso esta costa remota lejos de los impactos del protector solar químico, El pisoteo de los pies y las aguas residuales industriales está mostrando los primeros signos de lo que se espera sea una temporada catastrófica para los corales en Hawai.

Solo cuatro años después de que una gran ola de calor marina mató a casi la mitad de los corales de esta costa, Los investigadores federales predicen que otra ronda de agua caliente provocará una de las peores decoloraciones de corales que jamás haya experimentado la región.

"En 2015, alcanzamos temperaturas que nunca hemos registrado en Hawái, "dijo Jamison Gove, oceanógrafo de la Administración Nacional Oceánica y Atmosférica. "Lo que es realmente importante, o alarmante, probablemente sea más apropiado, acerca de este evento es que hemos estado rastreando por encima de donde estábamos en este momento en 2015 ".

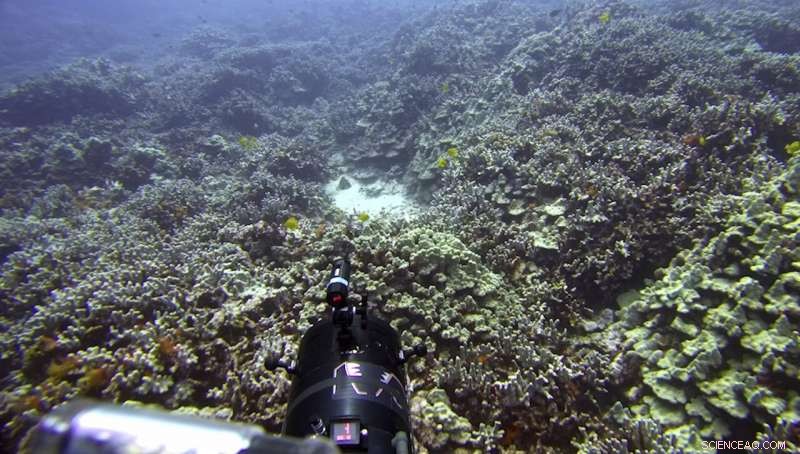

Los investigadores que utilizan equipos de alta tecnología para monitorear los arrecifes de Hawái están viendo signos tempranos de blanqueamiento en Papa Bay y en otros lugares causados por una ola de calor marino que ha elevado las temperaturas a niveles récord durante meses. Junio, Julio y partes de agosto experimentaron las temperaturas oceánicas más calientes jamás registradas alrededor de las islas hawaianas. En lo que va de septiembre Las temperaturas oceánicas están solo por debajo de las observadas en 2015.

Este 12 de septiembre La foto de 2019 muestra peces cerca de los corales en una bahía en la costa oeste de la Isla Grande cerca del Capitán Cook, Hawai. Solo cuatro años después de que una gran ola de calor marina mató a casi la mitad de los corales de esta costa, Los investigadores federales predicen que otra ronda de agua caliente provocará una de las peores decoloraciones de corales que jamás haya visto la región. (Foto AP / Brian Skoloff)

Los meteorólogos esperan que las altas temperaturas en el Pacífico norte continúen bombeando calor a las aguas de Hawái hasta bien entrado octubre.

"Las temperaturas han sido cálidas durante bastante tiempo, "Dijo Gove." No es sólo el calor que hace. Es el tiempo que permanecen calientes esas temperaturas oceánicas ".

Los arrecifes de coral son vitales en todo el mundo, ya que no solo proporcionan un hábitat para los peces, la base de la cadena alimentaria marina, sino también alimentos y medicinas para los humanos. También crean una barrera costera esencial que rompe las grandes marejadas oceánicas y protege las costas densamente pobladas de las marejadas ciclónicas durante los huracanes.

En Hawaii, Los arrecifes también son una parte importante de la economía:el turismo prospera en gran parte debido a los arrecifes de coral que ayudan a crear y proteger las icónicas playas de arena blanca, ofrecen lugares para practicar esnórquel y buceo, y ayuda a formar olas que atraen a surfistas de todo el mundo.

Este 12 de septiembre La foto de 2019 muestra un coral blanqueante en la bahía de Kahala'u en Kailua-Kona, Hawai. Solo cuatro años después de que una gran ola de calor marina mató a casi la mitad de los corales de esta costa, Los investigadores federales predicen que otra ronda de agua caliente provocará una de las peores decoloraciones de corales que jamás haya visto la región. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

Las temperaturas del océano no son uniformemente cálidas en todo el estado, Gove anotó. Patrones de viento locales, las corrientes e incluso las características de la tierra pueden crear puntos calientes en el agua.

"Tienes cosas como dos volcanes gigantes en la Isla Grande que bloquean los vientos alisios predominantes, "haciendo la costa oeste de la isla, donde se sienta Papa Bay, una de las partes más calientes del estado, Dijo Gove. Dijo que espera un blanqueamiento "severo" de los corales en esos lugares.

"Esto está muy extendido, Blanqueamiento al 100% de la mayoría de los corales, ", Dijo Gove. Y muchos de esos corales todavía se están recuperando del evento de blanqueamiento de 2015, lo que significa que son más susceptibles al estrés térmico.

Según NOAA, Las causas de la ola de calor incluyen un patrón meteorológico persistente de baja presión entre Hawai y Alaska que ha debilitado los vientos que de otra manera podrían mezclar y enfriar las aguas superficiales en gran parte del Pacífico Norte. No está claro cuál es la causa:podría reflejar el movimiento caótico habitual de la atmósfera, o podría estar relacionado con el calentamiento de los océanos y otros efectos del cambio climático provocado por el hombre.

En este 13 de septiembre, Imagen de 2019 tomada de un video proporcionado por el Centro de Descubrimiento Global y Ciencias de la Conservación de la Universidad Estatal de Arizona, El ecologista Greg Asner se sumerge en un arrecife de coral en Papa Bay cerca del Capitán Cook, Hawai. "Casi todas las especies que monitoreamos tienen al menos algo de blanqueamiento, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

Beyond this event, oceanic temperatures will continue to rise in the coming years, Gove said. "There's no question that global climate change is contributing to what we're experiencing, " él dijo.

For coral, hot water means stress, and prolonged stress kills these creatures and can leave reefs in shambles.

Bleaching occurs when stressed corals release algae that provide them with vital nutrients. That algae also gives the coral its color, so when it's expelled, the coral turns white.

Gove said researchers have a technological advantage for monitoring and gleaning insights into this year's bleaching, data that could help save reefs in the future.

"We're trying to track this event in real time via satellite, which is the first time that's ever been done, " Gove said.

In remote Papa Bay, most of the corals have recovered from the 2015 bleaching event, but scientists worry they won't fare as well this time.

In this Sept. 13, 2019, image taken from video provided by Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, ecologist Greg Asner prepares a camera fish trap on a coral reef in Papa Bay near Captain Cook, Hawai. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

"Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " said ecologist Greg Asner, director of Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, after a dive in the bay earlier this month.

Asner told The Associated Press that sensors showed the bay was about 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit above what is normal for this time of year.

He uses advanced imaging technology mounted to aircrafts, satellite data, underwater sensors and information from the public to give state and federal researchers like Gove the information they need.

"What's really important here is that we're taking these (underwater) measurements, connecting them to our aircraft data and then connecting them again to the satellite data, " Asner said. "That lets us scale up to see the big picture to get the truth about what's going on here."

In this Sept. 13, 2019 image taken from video provided by Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, ecologist Greg Asner dives over a coral reef in Papa Bay near Captain Cook, Hawai. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

Scientists will use the information to research, entre otras cosas, why some coral species are more resilient to thermal stress. Some of the latest research suggests slowly exposing coral to heat in labs can condition them to withstand hotter water in the future.

"After the heat wave ends, we will have a good map with which to plan restoration efforts, " Asner said.

Mientras tanto, Hawaii residents like Cindi Punihaole Kennedy are pitching in by volunteering to educate tourists. Punihaole Kennedy is director of the Kahalu'u Bay Education Center, a nonprofit created to help protect Kahalu'u Bay, a popular snorkeling spot near the Big Island's tourist center of Kailua-Kona.

The bay and surrounding beach park welcome more than 400, 000 visitors a year, ella dijo.

"We share with them what to do and what not to do as they enter the bay, " she said. "For instance, avoid stepping on the corals or feeding the fish."

In this Sept. 13, 2019 image taken from video provided by Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, ecologist Greg Asner dives over a coral reef in Papa Bay near Captain Cook, Hawai. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

In this Sept. 12, Foto 2019, fish swim near bleaching coral in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawai. Just four years after a major marine heat wave killed nearly half of this coastline's coral, federal researchers are predicting another round of hot water will cause some of the worst coral bleaching the region has ever seen. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 12, Foto 2019, sea urchins and fish are seen near bleaching coral in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawai. Just four years after a major marine heat wave killed nearly half of this coastline's coral, federal researchers are predicting another round of hot water will cause some of the worst coral bleaching the region has ever seen. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 12, Foto 2019, fish swim near bleaching coral in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawai. Coral reefs are vital around the world as they not only provide a habitat for fish—the base of the marine food chain—but food and medicine for humans. They also create an essential shoreline barrier that breaks apart large ocean swells and protects densely populated shorelines from storm surges during hurricanes. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 12, Foto 2019, visitors stand in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawai. Hawaii residents like Cindi Punihaole Kennedy are pitching in by volunteering to educate tourists. Punihaole Kennedy is director of the Kahalu'u Bay Education Center, a nonprofit created to help protect Kahalu'u Bay, a popular snorkeling spot near the Big Island's tourist center of Kailua-Kona. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

This Sept. 13, 2019 photo shows a chunk of bleached, dead coral shown on a wall near a bay on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawai. Coral reefs are vital around the world as they not only provide a habitat for fish—the base of the marine food chain—but food and medicine for humans. They also create an essential shoreline barrier that breaks apart large ocean swells and protects densely populated shorelines from storm surges during hurricanes. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 13, Foto 2019, researchers prepare to dive on a coral reef on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawai. One of the state's most vibrant coral reefs thrives just below the surface in a bay on the west coast of Hawaii's Big Island. Aquí, on a remote shoreline far from the impacts of sunscreen and throngs of tourists, scientists see the early signs of what's expected to be a catastrophic season of coral bleaching in Hawaii. The ocean here is about three and a half degrees above normal for this time of year. Coral can recover from bleaching, but when it is exposed to heat over several years, the likelihood of survival decreases. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 11, Foto 2019, a green sea turtle swims near coral in a bay on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawai. Just four years after a major marine heat wave killed nearly half of this coastline's coral, federal researchers are predicting another round of hot water will cause some of the worst coral bleaching the region has ever seen. (AP Photo/Brian Skoloff)

This Sept. 13, 2019 photo shows a chunk of bleached, dead coral shown on a wall near a bay on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawai. One of the state's most vibrant coral reefs thrives just below the surface in a bay on the west coast of Hawaii's Big Island. Aquí, on a remote shoreline far from the impacts of sunscreen and throngs of tourists, scientists see the early signs of what's expected to be a catastrophic season of coral bleaching in Hawaii. The ocean here is about three and a half degrees above normal for this time of year. Coral can recover from bleaching, but when it is exposed to heat over several years, the likelihood of survival decreases. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 13, Foto 2019, ecologist Greg Asner, the director of Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, reviews ocean temperature data at his lab on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawai. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " said Asner after a dive in Papa Bay. (AP Photo/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 16, Foto 2019, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration oceanographer Jamison Gove talks about coral bleaching at the NOAA regional office in Honolulu. U.S. federal researchers in Hawaii say ocean temperatures around the archipelago are on track to match or even surpass records set in 2015, the hottest year on record for the Pacific Ocean. They predict that heat will cause some of the worst coral bleaching and mortality the region has ever seen. (Foto AP / Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 13, Foto 2019, ecologist Greg Asner, the director of Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, reviews ocean temperature data at his lab on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawai. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " said Asner after a dive in Papa Bay. (AP Photo/Caleb Jones)

The bay suffered widespread bleaching and coral death in 2015.

"It was devastating for us to not be able to do anything, " Punihaole Kennedy said. "We just watched the corals die."

© 2019 The Associated Press. Reservados todos los derechos.