Crédito:Shutterstock

Cuando conectamos pequeños dispositivos de rastreo similares a mochilas a cinco urracas australianas para un estudio piloto, no esperábamos descubrir un comportamiento social completamente nuevo que rara vez se ve en las aves.

Nuestro objetivo era aprender más sobre el movimiento y la dinámica social de estas aves altamente inteligentes y probar estos dispositivos nuevos, duraderos y reutilizables. En cambio, los pájaros nos engañaron.

Como explica nuestro nuevo trabajo de investigación, las urracas comenzaron a mostrar evidencia de un comportamiento cooperativo de "rescate" para ayudarse mutuamente a eliminar el rastreador.

Si bien estamos familiarizados con las urracas como criaturas inteligentes y sociales, esta fue la primera vez que supimos que mostró este tipo de comportamiento aparentemente altruista:ayudar a otro miembro del grupo sin obtener una recompensa inmediata y tangible.

Probando nuevos y emocionantes dispositivos

Como científicos académicos, estamos acostumbrados a que los experimentos salgan mal de una forma u otra. Sustancias caducadas, equipos defectuosos, muestras contaminadas, un corte de energía no planificado:todo esto puede retrasar meses (o incluso años) de investigación cuidadosamente planificada.

Para aquellos de nosotros que estudiamos animales, y especialmente el comportamiento, la imprevisibilidad es parte de la descripción del trabajo. Esta es la razón por la que a menudo requerimos estudios piloto.

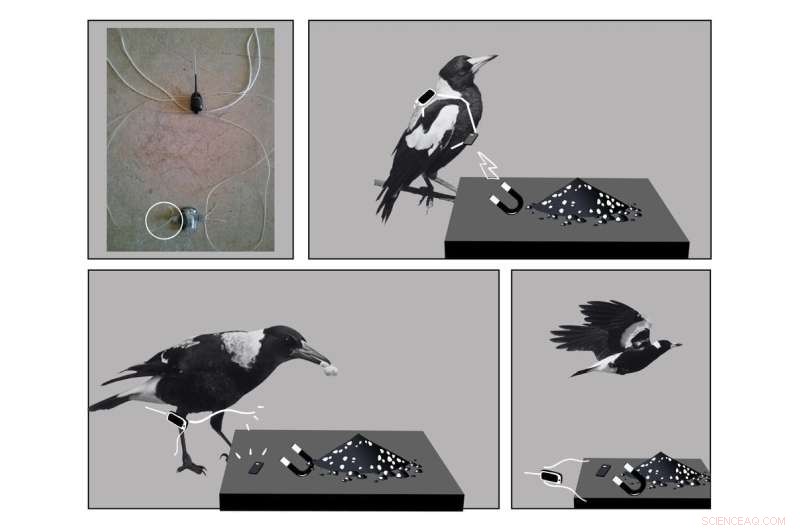

Uno de los rastreadores que adjuntamos a cinco urracas, que pesa menos de un gramo. Crédito:Dominique Potvin, proporcionado por el autor

Nuestro estudio piloto fue uno de los primeros de su tipo:la mayoría de los rastreadores son demasiado grandes para caber en aves medianas o pequeñas, y los que lo hacen tienden a tener una capacidad muy limitada de almacenamiento de datos o duración de la batería. También tienden a ser de un solo uso.

Un aspecto novedoso de nuestra investigación fue el diseño del arnés que sujetaba el rastreador. Ideamos un método que no requería que las aves fueran capturadas nuevamente para descargar datos valiosos o reutilizar los pequeños dispositivos.

Capacitamos a un grupo de urracas locales para que llegaran a una "estación" de alimentación terrestre al aire libre que podría cargar de forma inalámbrica la batería del rastreador, descargar datos o liberar el rastreador y el arnés mediante el uso de un imán.

El arnés era resistente, con solo un punto débil donde el imán podía funcionar. Para quitar el arnés, uno necesitaba ese imán o unas tijeras realmente buenas. Estábamos entusiasmados con el diseño, ya que abrió muchas posibilidades de eficiencia y permitió recopilar una gran cantidad de datos.

We wanted to see if the new design would work as planned, and discover what kind of data we could gather. How far did magpies go? Did they have patterns or schedules throughout the day in terms of movement, and socialising? How did age, sex or dominance rank affect their activities?

All this could be uncovered using the tiny trackers—weighing less than one gram—we successfully fitted five of the magpies with. All we had to do was wait, and watch, and then lure the birds back to the station to gather the valuable data.

It was not to be

Many animals that live in societies cooperate with one another to ensure the health, safety and survival of the group. In fact, cognitive ability and social cooperation has been found to correlate. Animals living in larger groups tend to have an increased capacity for problem solving, such as hyenas, spotted wrasse, and house sparrows.

Australian magpies are no exception. As a generalist species that excels in problem solving, it has adapted well to the extreme changes to their habitat from humans.

Australian magpies generally live in social groups of between two and 12 individuals, cooperatively occupying and defending their territory through song choruses and aggressive behaviors (such as swooping). These birds also breed cooperatively, with older siblings helping to raise young.

During our pilot study, we found out how quickly magpies team up to solve a group problem. Within ten minutes of fitting the final tracker, we witnessed an adult female without a tracker working with her bill to try and remove the harness off of a younger bird.

Within hours, most of the other trackers had been removed. By day 3, even the dominant male of the group had its tracker successfully dismantled.

We don't know if it was the same individual helping each other or if they shared duties, but we had never read about any other bird cooperating in this way to remove tracking devices.

Our new tracker design was innovative, allowing a magnet to release the harness. Credit:Dominique Potvin, Author provided

The birds needed to problem solve, possibly testing at pulling and snipping at different sections of the harness with their bill. They also needed to willingly help other individuals, and accept help.

The only other similar example of this type of behavior we could find in the literature was that of Seychelles warblers helping release others in their social group from sticky Pisonia seed clusters. This is a very rare behavior termed "rescuing."

Saving magpies

So far, most bird species that have been tracked haven't necessarily been very social or considered to be cognitive problem solvers, such as waterfowl and raptors. We never considered the magpies may perceive the tracker as some kind of parasite that requires removal.

Tracking magpies is crucial for conservation efforts, as these birds are vulnerable to the increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves under climate change.

In a study published this week, Perth researchers showed the survival rate of magpie chicks in heatwaves can be as low as 10%.

Importantly, they also found that higher temperatures resulted in lower cognitive performance for tasks such as foraging. This might mean cooperative behaviors become even more important in a continuously warming climate.

Just like magpies, we scientists are always learning to problem solve. Now we need to go back to the drawing board to find ways of collecting more vital behavioral data to help magpies survive in a changing world.