Los alquimistas antiguos intentaron convertir el plomo y otros metales comunes en oro y platino. Los químicos modernos del laboratorio de Paul Chirik en Princeton están transformando reacciones que han dependido de metales preciosos nocivos para el medio ambiente. encontrar alternativas más baratas y ecológicas para reemplazar el platino, rodio y otros metales preciosos en la producción de fármacos y otras reacciones.

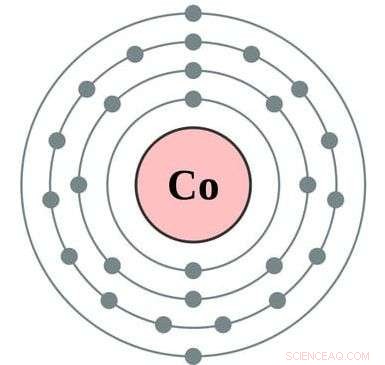

Han encontrado un enfoque revolucionario que utiliza cobalto y metanol para producir un fármaco para la epilepsia que antes requería rodio y diclorometano. un solvente tóxico. Su nueva reacción funciona de forma más rápida y económica, y probablemente tenga un impacto ambiental mucho menor, dijo Chirik, el profesor de química Edwards S. Sanford. "Esto destaca un principio importante en la química verde:que la solución más ambiental también puede ser la preferida químicamente, ", dijo. La investigación fue publicada en la revista Ciencias el 25 de mayo.

"El descubrimiento y el proceso farmacéutico involucran todo tipo de elementos exóticos, ", Dijo Chirik." Comenzamos este programa hace unos 10 años, y estaba realmente motivado por el costo. Los metales como el rodio y el platino son muy caros, pero a medida que la obra ha ido evolucionando, nos dimos cuenta de que hay mucho más que simplemente fijar precios. ... Hay enormes preocupaciones medioambientales, si piensas en desenterrar platino del suelo. Típicamente, tienes que ir a una milla de profundidad y mover 10 toneladas de tierra. Eso tiene una enorme huella de dióxido de carbono ".

Chirik y su equipo de investigación se asociaron con químicos de Merck &Co., C ª., para encontrar formas más ecológicas de crear los materiales necesarios para la química farmacéutica moderna. La colaboración ha sido posible gracias al programa de Oportunidades de Subvenciones para el Enlace Académico con la Industria (GOALI) de la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias.

Un aspecto complicado es que muchas moléculas tienen formas para diestros y zurdos que reaccionan de manera diferente, con consecuencias a veces peligrosas. La Administración de Alimentos y Medicamentos tiene requisitos estrictos para asegurarse de que los medicamentos tengan solo una "mano" a la vez, conocidos como fármacos de un solo enantiómero.

"Los químicos tienen el desafío de descubrir métodos para sintetizar solo una mano de moléculas de fármaco en lugar de sintetizar ambas y luego separarlas, "dijo Chirik." Catalizadores metálicos, históricamente basado en metales preciosos como el rodio, se les ha encomendado la tarea de resolver este desafío. Nuestro artículo demuestra que un metal más abundante en la Tierra, cobalto, se puede utilizar para sintetizar el medicamento para la epilepsia Keppra en una sola mano ".

Hace cinco años, Los investigadores del laboratorio de Chirik demostraron que el cobalto podía producir moléculas orgánicas de un solo enantiómero, pero solo usando compuestos relativamente simples y no medicinalmente activos, y usando solventes tóxicos.

"Nos inspiró para llevar nuestra demostración de principios a ejemplos del mundo real y demostrar que el cobalto podía superar a los metales preciosos y trabajar en condiciones más compatibles con el medio ambiente". ", dijo. Descubrieron que su nueva técnica basada en cobalto es más rápida y selectiva que el enfoque patentado de rodio.

"Nuestro artículo demuestra un caso raro en el que un metal de transición abundante en la Tierra puede superar el rendimiento de un metal precioso en la síntesis de fármacos de un solo enantiómero, ", dijo." A lo que estamos comenzando a hacer la transición es a que los catalizadores abundantes en la Tierra no solo reemplazan a los de metales preciosos, pero ofrecen distintas ventajas, ya sea una nueva química que nadie ha visto antes o una reactividad mejorada o una huella ambiental reducida ".

Los metales básicos no solo son más baratos y mucho más respetuosos con el medio ambiente que los metales raros, pero la nueva técnica opera en metanol, which is much greener than the chlorinated solvents that rhodium requires.

"The manufacture of drug molecules, because of their complexity, is one of the most wasteful processes in the chemical industry, " said Chirik. "The majority of the waste generated is from the solvent used to conduct the reaction. The patented route to the drug relies on dichloromethane, one of the least environmentally friendly organic solvents. Our work demonstrates that Earth-abundant catalysts not only operate in methanol, a green solvent, but also perform optimally in this medium.

"This is a transformative breakthrough for Earth-abundant metal catalysts, as these historically have not been as robust as precious metals. Our work demonstrates that both the metal and the solvent medium can be more environmentally compatible."

Methanol is a common solvent for one-handed chemistry using precious metals, but this is the first time it has been shown to be useful in a cobalt system, noted Max Friedfeld, the first author on the paper and a former graduate student in Chirik's lab.

Cobalt's affinity for green solvents came as a surprise, said Chirik. "For a decade, catalysts based on Earth-abundant metals like iron and cobalt required very dry and pure conditions, meaning the catalysts themselves were very fragile. By operating in methanol, not only is the environmental profile of the reaction improved, but the catalysts are much easier to use and handle. This means that cobalt should be able to compete or even outperform precious metals in many applications that extend beyond hydrogenation."

The collaboration with Merck was key to making these discoveries, noted the researchers.

Chirik said:"This is a great example of an academic-industrial collaboration and highlights how the very fundamental—how do electrons flow differently in cobalt versus rhodium?—can inform the applied—how to make an important medicine in a more sustainable way. I think it is safe to say that we would not have discovered this breakthrough had the two groups at Merck and Princeton acted on their own."

The key was volume, said Michael Shevlin, an associate principal scientist at the Catalysis Laboratory in the Department of Process Research &Development at Merck &Co., C ª., and a co-author on the paper.

"Instead of trying just a few experiments to test a hypothesis, we can quickly set up large arrays of experiments that cover orders of magnitude more chemical space, " Shevlin said. "The synergy is tremendous; scientists like Max Friedfeld and [co-author and graduate student] Aaron Zhong can conduct hundreds of experiments in our lab, and then take the most interesting results back to Princeton to study in detail. What they learn there then informs the next round of experimentation here."

Chirik's lab focuses on "homogenous catalysis, " the term for reactions using materials that have been dissolved in industrial solvents.

"Homogenous catalysis is usually the realm of these precious metals, the ones at the bottom of the periodic table, " Chirik said. "Because of their position on the periodic table, they tend to go by very predictable electron changes—two at a time—and that's why you can make jewelry out of these elements, because they don't oxidize, they don't interact with oxygen. So when you go to the Earth-abundant elements, usually the ones on the first row of the periodic table, the electronic structure—how the electrons move in the element—changes, and so you start getting one-electron chemistry, and that's why you see things like rust for these elements.

Chirik's approach proposes a radical shift for the whole field, said Vy Dong, a chemistry professor at the University of California-Irvine who was not involved in the research. "Traditional chemistry happens through what they call two-electron oxidations, and Paul's happens through one-electron oxidation, " she said. "That doesn't sound like a big difference, but that's a dramatic difference for a chemist. That's what we care about—how things work at the level of electrons and atoms. When you're talking about a pathway that happens via half of the electrons that you'd normally expect, it's a big deal. ... That's why this work is really exciting. You can imagine, once we break free from that mold, you can start to apply it to other things, también."

"We're working in an area of the periodic table where people haven't, por mucho tiempo, so there's a huge wealth of new fundamental chemistry, " said Chirik. "By learning how to control this electron flow, the world is open to us."