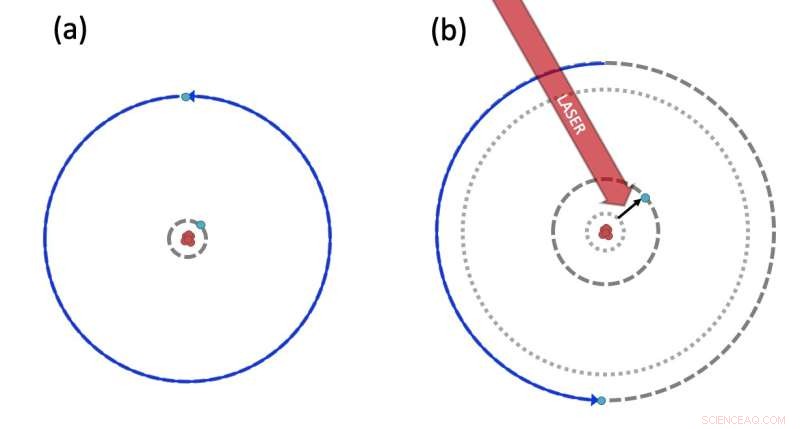

En ausencia del pulso láser, el electrón de Rydberg orbita alrededor del núcleo en una trayectoria circular (flecha azul). (b) Cuando un pulso de láser transfiere el electrón interno a una órbita excitada, la fuerza electrostática empuja al electrón de Rydberg hacia una órbita más grande, donde gira más lentamente. Crédito:Eva-Katharina Dietsche

Los átomos de Rydberg son átomos excitados que contienen uno o más electrones con un número cuántico principal alto. Debido a su gran tamaño, interacciones dipolo-dipolo de largo alcance y fuerte acoplamiento a campos externos, estos átomos han demostrado ser sistemas prometedores para el desarrollo de tecnologías cuánticas.

A pesar de sus ventajas, los físicos descubrieron que los estados de Rydberg ópticamente accesibles tienden a tener una vida útil corta, lo que limita su rendimiento en la tecnología cuántica. Una posible solución a este problema podría ser utilizar estados circulares de Rydberg, con vidas más largas, aunque hasta ahora su detección óptica ha resultado difícil.

Investigadores de la ENS-University PSL, la Sorbonne Université, la Université Paris-Saclay y la Universidade Federal de São Carlos han demostrado recientemente la manipulación coherente de un estado Rydberg circular utilizando pulsos ópticos. Sus resultados, descritos en un artículo publicado en Nature Physics , podría abrir nuevas posibilidades para el desarrollo de una plataforma híbrida de microondas óptico para tecnologías cuánticas.

"Los átomos alcalinotérreos son interesantes para la física de Rydberg, porque una vez que el primer electrón está en el estado de Rydberg, tienen un segundo electrón que aún puede usarse para manipular el átomo con láseres", Sébastien Gleyzes, uno de los investigadores que llevó a cabo el estudio, dijo a Phys.org. "Sin embargo, un problema es que, si la 'trayectoria' del electrón de Rydberg (es decir, su función de onda) es demasiado elíptica, cuando el segundo electrón se excita con el láser, los dos electrones pueden chocar, lo que lleva a la autoionización del átomo".

En sus experimentos, Gleyzes y sus colegas utilizaron estados circulares de Rydberg, estados en los que la trayectoria/función de onda de un átomo de Rydberg está 'a un círculo de distancia' del núcleo iónico. Debido a esta organización circular, cuando se excita un segundo electrón dentro del átomo, existe una posibilidad muy pequeña de que colisione con el primero.

"Nuestro objetivo inicial era demostrar que podíamos excitar el segundo electrón sin que el átomo se ionizara", dijo Gleyzes. "Sin embargo, durante el transcurso del experimento, observamos que la frecuencia de transición entre dos estados Rydberg circulares era diferente dependiendo de si el segundo electrón estaba en un estado excitado o no".

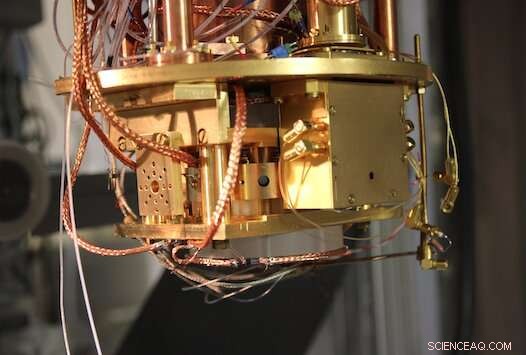

Picture of the experimental set-up before it is sealed inside the cryostat and cooled down with liquid helium. Credit:Eva-Katharina Dietsche.

Essentially, the researchers found that even though the two valence electrons inside a Rydberg atom remain far away from each other in circular Rydberg states, they can still 'feel each other's presence' through the electrostatic force. They then showed that this 'electrostatic coupling' between the two electrons could be used to coherently manipulate the circular Rydberg state using optical pulses.

"In a classical picture, the frequency at which the Rydberg electron rotates depends on the state of the ionic core electron (let's call it 'up' or 'down')," Gleyzes explained. "We prepared the electron at given position on the orbit and waited for a time T such that the Rydberg electron makes an integer number of rotation if the ionic core is in 'down'. To optically change the state of the Rydberg electron, we transiently send the ionic core electron into other state ('up') with a laser pulse."

By sending the ionic core electron into the second desired state, the researchers slowed down the motion of the electron, which ultimately ends up on the other side of the orbit at the end of the waiting time (i.e., T). In other words, they were able to control the state of the Rydberg electron (which fluctuated between one side and the other of the orbit) by applying or removing a laser pulse.

"We thought that the alkaline earth Rydberg atoms would be interesting because one electron would be used for the quantum processes and the other electron would be used to control the motion of the atom (cool the atom or trap the atom)," Gleyzes said. "Before our study, though, we thought that they would work independently."

The technique to optically manipulate alkaline-earth circular Rydberg states introduced by this team of researchers could open interesting possibilities for the development of quantum technology. In fact, their work is the first to show that the two valence electrons inside alkaline-earth Rydberg atoms are not entirely independent, thus scientists could use one of them to manipulate the other or to detect the other's states.

"The possibility of conditioning the fluorescence of the ionic core electron to the state of the Rydberg electron is extremely promising, for instance if one wants to measure the state of the Rydberg electron non-destructively," Gleyzes added. "Our team's long-term goal is to build a quantum simulator based on the circular states of alkaline-earth atoms."

© 2022 Red Ciencia X First successful laser trapping of circular Rydberg atoms