Una selva tropical en América del Sur. Crédito:Shutterstock / BorneoRimbawan

Una mañana de 2009 Me senté en un autobús chirriante que serpenteaba por la ladera de una montaña en el centro de Costa Rica, mareado por los vapores del diesel mientras agarraba mis muchas maletas. Contenían miles de tubos de ensayo y viales de muestra, un cepillo de dientes, un cuaderno a prueba de agua y dos mudas de ropa.

Iba camino a la Estación Biológica La Selva, donde iba a pasar varios meses estudiando la humedad, la respuesta de la selva baja a las sequías cada vez más comunes. A ambos lados de la carretera estrecha, los árboles se desangraron en la niebla como acuarelas en papel, dando la impresión de un bosque primitivo infinito bañado por nubes.

Mientras miraba por la ventana el imponente paisaje, Me pregunté cómo podía esperar comprender un paisaje tan complejo. Sabía que miles de investigadores de todo el mundo estaban lidiando con las mismas preguntas, tratando de comprender el destino de los bosques tropicales en un mundo que cambia rápidamente.

Nuestra sociedad pide tanto a estos frágiles ecosistemas, que controlan la disponibilidad de agua dulce para millones de personas y albergan dos tercios de la biodiversidad terrestre del planeta. Y cada vez más hemos puesto una nueva demanda en estos bosques:para salvarnos del cambio climático causado por el hombre.

Las plantas absorben CO 2 de la atmósfera, transformándolo en hojas, madera y raíces. Este milagro cotidiano ha estimulado la esperanza de que las plantas, en particular los árboles tropicales de rápido crecimiento, puedan actuar como un freno natural al cambio climático. capturando gran parte del CO 2 emitida por la quema de combustibles fósiles. Alrededor del mundo, gobiernos empresas y organizaciones benéficas de conservación se han comprometido a conservar o plantar una gran cantidad de árboles.

Pero el hecho es que no hay suficientes árboles para compensar las emisiones de carbono de la sociedad, y nunca los habrá. Recientemente realicé una revisión de la literatura científica disponible para evaluar cuánto carbono podrían absorber los bosques. Si maximizáramos absolutamente la cantidad de vegetación que toda la tierra de la Tierra podría contener, secuestraríamos suficiente carbono para compensar unos diez años de emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero al ritmo actual. Después, no podría haber más aumento en la captura de carbono.

Sin embargo, el destino de nuestra especie está indisolublemente ligado a la supervivencia de los bosques y la biodiversidad que contienen. Al apresurarse a plantar millones de árboles para la captura de carbono, ¿Podríamos estar dañando inadvertidamente las mismas propiedades del bosque que los hacen tan vitales para nuestro bienestar? Para responder a esta pregunta, debemos considerar no solo cómo las plantas absorben CO 2 , sino también cómo proporcionan las sólidas bases verdes para los ecosistemas terrestres.

Cómo las plantas luchan contra el cambio climático

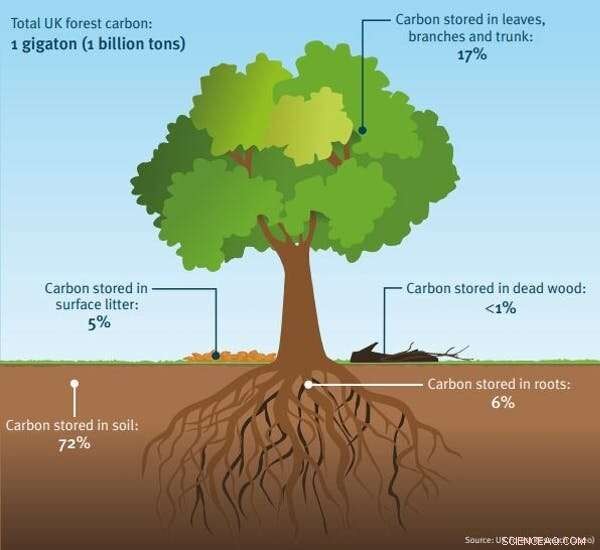

Las plantas convierten CO 2 gas en azúcares simples en un proceso conocido como fotosíntesis. Estos azúcares luego se utilizan para construir los cuerpos vivos de las plantas. Si el carbono capturado termina en madera, puede permanecer alejado de la atmósfera durante muchas décadas. Mientras las plantas mueren sus tejidos se descomponen y se incorporan al suelo.

Bonnie Waring realizando una investigación en la Estación Biológica La Selva, Costa Rica, 2011. Autor proporcionado

Si bien este proceso libera CO de forma natural 2 a través de la respiración (o respiración) de microbios que descomponen los organismos muertos, alguna fracción del carbono vegetal puede permanecer bajo tierra durante décadas o incluso siglos. Juntos, las plantas terrestres y los suelos contienen alrededor de 2, 500 gigatoneladas de carbono, aproximadamente tres veces más de lo que se mantiene en la atmósfera.

Debido a que las plantas (especialmente los árboles) son excelentes depósitos naturales de carbono, Tiene sentido que aumentar la abundancia de plantas en todo el mundo podría reducir el CO atmosférico 2 concentraciones.

Las plantas necesitan cuatro ingredientes básicos para crecer:luz, CO 2 , agua y nutrientes (como nitrógeno y fósforo, los mismos elementos presentes en el fertilizante vegetal). Miles de científicos de todo el mundo estudian cómo varía el crecimiento de las plantas en relación con estos cuatro ingredientes, para predecir cómo responderá la vegetación al cambio climático.

Esta es una tarea sorprendentemente desafiante, dado que los humanos están modificando simultáneamente muchos aspectos del entorno natural al calentar el mundo, alteración de los patrones de lluvia, cortando grandes extensiones de bosque en pequeños fragmentos e introduciendo especies exóticas donde no pertenecen. También hay más de 350, 000 especies de plantas con flores en la tierra y cada una responde a los desafíos ambientales de manera única.

Debido a las complicadas formas en que los humanos están alterando el planeta, Existe un gran debate científico sobre la cantidad precisa de carbono que las plantas pueden absorber de la atmósfera. Pero los investigadores están de acuerdo unánimemente en que los ecosistemas terrestres tienen una capacidad finita para absorber carbono.

Si nos aseguramos de que los árboles tengan suficiente agua para beber, los bosques crecerán altos y frondosos, creando toldos sombreados que privan de luz a los árboles más pequeños. Si aumentamos la concentración de CO 2 en el aire, las plantas lo absorberán con entusiasmo, hasta que ya no puedan extraer suficiente fertilizante del suelo para satisfacer sus necesidades. Como un panadero haciendo un pastel las plantas requieren CO 2 , nitrógeno y fósforo en proporciones particulares, siguiendo una receta específica para la vida.

En reconocimiento de estas limitaciones fundamentales, Los científicos estiman que los ecosistemas terrestres de la tierra pueden contener suficiente vegetación adicional para absorber entre 40 y 100 gigatoneladas de carbono de la atmósfera. Una vez que se logre este crecimiento adicional (un proceso que llevará varias décadas), no hay capacidad para almacenamiento adicional de carbono en tierra.

Pero nuestra sociedad está vertiendo CO 2 a la atmósfera a razón de diez gigatoneladas de carbono al año. Los procesos naturales lucharán por mantenerse al día con el diluvio de gases de efecto invernadero generados por la economía global. Por ejemplo, Calculé que un solo pasajero en un vuelo de ida y vuelta desde Melbourne a la ciudad de Nueva York emitirá aproximadamente el doble de carbono (1600 kg C) que el contenido en un roble de medio metro de diámetro (750 kg C).

Hoja al microscopio:se puede ver el estoma que regula el oxígeno y el dióxido de carbono. Crédito:Shutterstock / Barbol

Peligro y promesa

A pesar de todas estas limitaciones físicas bien reconocidas sobre el crecimiento de las plantas, Existe un número creciente de esfuerzos a gran escala para aumentar la cobertura vegetal para mitigar la emergencia climática, una solución climática llamada "basada en la naturaleza". La gran mayoría de estos esfuerzos se enfocan en proteger o expandir los bosques, ya que los árboles contienen muchas veces más biomasa que los arbustos o pastos y, por lo tanto, representan un mayor potencial de captura de carbono.

Sin embargo, los malentendidos fundamentales sobre la captura de carbono por los ecosistemas terrestres pueden tener consecuencias devastadoras, resultando en pérdidas de biodiversidad y un aumento de CO 2 concentraciones. Esto parece una paradoja:¿cómo puede la plantación de árboles impactar negativamente el medio ambiente?

La respuesta radica en las sutiles complejidades de la captura de carbono en los ecosistemas naturales. Para evitar daños ambientales, debemos abstenernos de establecer bosques donde naturalmente no pertenecen, evitar "incentivos perversos" para talar el bosque existente con el fin de plantar nuevos árboles, y considere cómo les iría a las plántulas plantadas hoy en las próximas décadas.

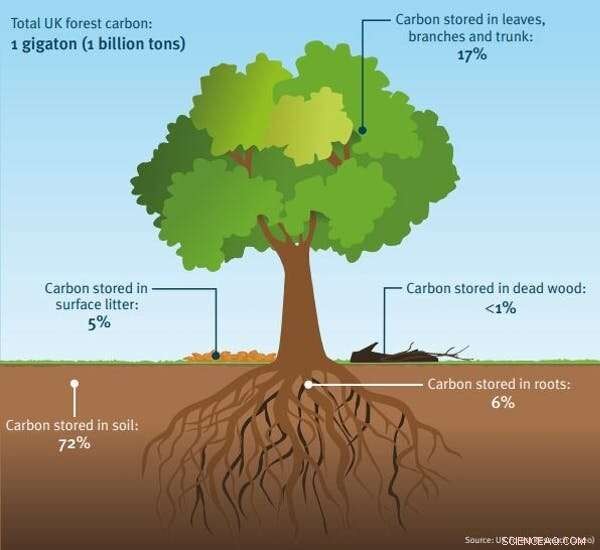

Antes de emprender cualquier expansión del hábitat forestal, debemos asegurarnos de que los árboles se planten en el lugar correcto porque no todos los ecosistemas de la tierra pueden o deben sustentar árboles. La plantación de árboles en ecosistemas que normalmente están dominados por otros tipos de vegetación a menudo no da como resultado el secuestro de carbono a largo plazo.

Un ejemplo particularmente ilustrativo proviene de las turberas escocesas:vastas extensiones de tierra donde la vegetación baja (principalmente musgos y pastos) crece en constante humedad, suelo húmedo. Debido a que la descomposición es muy lenta en suelos ácidos y anegados, las plantas muertas se acumulan durante períodos de tiempo muy largos, creando turba. No solo se conserva la vegetación:las turberas también momifican los llamados "cuerpos de los pantanos", los restos casi intactos de hombres y mujeres que murieron hace milenios. De hecho, Las turberas del Reino Unido contienen 20 veces más carbono que el que se encuentra en los bosques del país.

Pero a finales del siglo XX, algunos pantanos escoceses fueron drenados para plantar árboles. El secado de los suelos permitió que las plántulas de árboles se establecieran, pero también provocó que la descomposición de la turba se acelerara. La ecologista Nina Friggens y sus colegas de la Universidad de Exeter estimaron que la descomposición de la turba seca liberaba más carbono del que los árboles en crecimiento podían absorber. Claramente, Las turberas pueden proteger mejor el clima cuando se las deja a su suerte.

Lo mismo ocurre con los pastizales y las sabanas, donde los incendios son una parte natural del paisaje y a menudo queman árboles que se plantan donde no pertenecen. Este principio también se aplica a las tundras árticas, donde la vegetación autóctona está cubierta de nieve durante todo el invierno, reflejando la luz y el calor de regreso al espacio. Plantando alto Los árboles de hojas oscuras en estas áreas pueden aumentar la absorción de energía térmica, y conducir al calentamiento local.

Pero incluso plantar árboles en hábitats forestales puede tener consecuencias ambientales negativas. From the perspective of both carbon sequestration and biodiversity, all forests are not equal—naturally established forests contain more species of plants and animals than plantation forests. They often hold more carbon, también. But policies aimed at promoting tree planting can unintentionally incentivise deforestation of well established natural habitats.

Where carbon is stored in a typical temperate forest in the UK. Credit:UK Forest Research, CC BY

A recent high-profile example concerns the Mexican government's Sembrando Vida program, which provides direct payments to landowners for planting trees. The problem? Many rural landowners cut down well established older forest to plant seedlings. This decision, while quite sensible from an economic point of view, has resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of hectares of mature forest.

This example demonstrates the risks of a narrow focus on trees as carbon absorption machines. Many well meaning organizations seek to plant the trees which grow the fastest, as this theoretically means a higher rate of CO 2 "drawdown" from the atmosphere.

Yet from a climate perspective, what matters is not how quickly a tree can grow, but how much carbon it contains at maturity, and how long that carbon resides in the ecosystem. As a forest ages, it reaches what ecologists call a "steady state"—this is when the amount of carbon absorbed by the trees each year is perfectly balanced by the CO 2 released through the breathing of the plants themselves and the trillions of decomposer microbes underground.

This phenomenon has led to an erroneous perception that old forests are not useful for climate mitigation because they are no longer growing rapidly and sequestering additional CO 2 . The misguided "solution" to the issue is to prioritize tree planting ahead of the conservation of already established forests. This is analogous to draining a bathtub so that the tap can be turned on full blast:the flow of water from the tap is greater than it was before—but the total capacity of the bath hasn't changed. Mature forests are like bathtubs full of carbon. They are making an important contribution to the large, but finite, quantity of carbon that can be locked away on land, and there is little to be gained by disturbing them.

What about situations where fast growing forests are cut down every few decades and replanted, with the extracted wood used for other climate-fighting purposes? While harvested wood can be a very good carbon store if it ends up in long lived products (like houses or other buildings), surprisingly little timber is used in this way.

Similar, burning wood as a source of biofuel may have a positive climate impact if this reduces total consumption of fossil fuels. But forests managed as biofuel plantations provide little in the way of protection for biodiversity and some research questions the benefits of biofuels for the climate in the first place.

Fertilize a whole forest

Scientific estimates of carbon capture in land ecosystems depend on how those systems respond to the mounting challenges they will face in the coming decades. All forests on Earth—even the most pristine—are vulnerable to warming, changes in rainfall, increasingly severe wildfires and pollutants that drift through the Earth's atmospheric currents.

Some of these pollutants, sin embargo, contain lots of nitrogen (plant fertilizer) which could potentially give the global forest a growth boost. By producing massive quantities of agricultural chemicals and burning fossil fuels, humans have massively increased the amount of "reactive" nitrogen available for plant use. Some of this nitrogen is dissolved in rainwater and reaches the forest floor, where it can stimulate tree growth in some areas.

Implications of large-scale tree planting in various climatic zones and ecosystems. Credit:Stacey McCormack/Köppen climate classification, Autor proporcionado

As a young researcher fresh out of graduate school, I wondered whether a type of under-studied ecosystem, known as seasonally dry tropical forest, might be particularly responsive to this effect. There was only one way to find out:I would need to fertilize a whole forest.

Working with my postdoctoral adviser, the ecologist Jennifer Powers, and expert botanist Daniel Pérez Avilez, I outlined an area of the forest about as big as two football fields and divided it into 16 plots, which were randomly assigned to different fertilizer treatments. For the next three years (2015-2017) the plots became among the most intensively studied forest fragments on Earth. We measured the growth of each individual tree trunk with specialised, hand-built instruments called dendrometers.

We used baskets to catch the dead leaves that fell from the trees and installed mesh bags in the ground to track the growth of roots, which were painstakingly washed free of soil and weighed. The most challenging aspect of the experiment was the application of the fertilizers themselves, which took place three times a year. Wearing raincoats and goggles to protect our skin against the caustic chemicals, we hauled back-mounted sprayers into the dense forest, ensuring the chemicals were evenly applied to the forest floor while we sweated under our rubber coats.

Desafortunadamente, our gear didn't provide any protection against angry wasps, whose nests were often concealed in overhanging branches. But, our efforts were worth it. After three years, we could calculate all the leaves, wood and roots produced in each plot and assess carbon captured over the study period. We found that most trees in the forest didn't benefit from the fertilizers—instead, growth was strongly tied to the amount of rainfall in a given year.

This suggests that nitrogen pollution won't boost tree growth in these forests as long as droughts continue to intensify. To make the same prediction for other forest types (wetter or drier, younger or older, warmer or cooler) such studies will need to be repeated, adding to the library of knowledge developed through similar experiments over the decades. Yet researchers are in a race against time. Experiments like this are slow, painstaking, sometimes backbreaking work and humans are changing the face of the planet faster than the scientific community can respond.

Humans need healthy forests

Supporting natural ecosystems is an important tool in the arsenal of strategies we will need to combat climate change. But land ecosystems will never be able to absorb the quantity of carbon released by fossil fuel burning. Rather than be lulled into false complacency by tree planting schemes, we need to cut off emissions at their source and search for additional strategies to remove the carbon that has already accumulated in the atmosphere.

Does this mean that current campaigns to protect and expand forest are a poor idea? Emphatically not. The protection and expansion of natural habitat, particularly forests, is absolutely vital to ensure the health of our planet. Forests in temperate and tropical zones contain eight out of every ten species on land, yet they are under increasing threat. Nearly half of our planet's habitable land is devoted to agriculture, and forest clearing for cropland or pasture is continuing apace.

Mientras tanto, the atmospheric mayhem caused by climate change is intensifying wildfires, worsening droughts and systematically heating the planet, posing an escalating threat to forests and the wildlife they support. What does that mean for our species? Again and again, researchers have demonstrated strong links between biodiversity and so-called "ecosystem services"—the multitude of benefits the natural world provides to humanity.

Dendrometer devices wrapped around tree trunks to measure growth. Autor proporcionado

Carbon capture is just one ecosystem service in an incalculably long list. Biodiverse ecosystems provide a dizzying array of pharmaceutically active compounds that inspire the creation of new drugs. They provide food security in ways both direct (think of the millions of people whose main source of protein is wild fish) and indirect (for example, a large fraction of crops are pollinated by wild animals).

Natural ecosystems and the millions of species that inhabit them still inspire technological developments that revolutionize human society. Por ejemplo, take the polymerase chain reaction ("PCR") that allows crime labs to catch criminals and your local pharmacy to provide a COVID test. PCR is only possible because of a special protein synthesized by a humble bacteria that lives in hot springs.

As an ecologist, I worry that a simplistic perspective on the role of forests in climate mitigation will inadvertently lead to their decline. Many tree planting efforts focus on the number of saplings planted or their initial rate of growth—both of which are poor indicators of the forest's ultimate carbon storage capacity and even poorer metric of biodiversity. Más importante, viewing natural ecosystems as "climate solutions" gives the misleading impression that forests can function like an infinitely absorbent mop to clean up the ever increasing flood of human caused CO 2 emisiones.

Luckily, many big organizations dedicated to forest expansion are incorporating ecosystem health and biodiversity into their metrics of success. A little over a year ago, I visited an enormous reforestation experiment on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, operated by Plant-for-the-Planet—one of the world's largest tree planting organizations. After realizing the challenges inherent in large scale ecosystem restoration, Plant-for-the-Planet has initiated a series of experiments to understand how different interventions early in a forest's development might improve tree survival.

But that is not all. Led by Director of Science Leland Werden, researchers at the site will study how these same practices can jump-start the recovery of native biodiversity by providing the ideal environment for seeds to germinate and grow as the forest develops. These experiments will also help land managers decide when and where planting trees benefits the ecosystem and where forest regeneration can occur naturally.

Viewing forests as reservoirs for biodiversity, rather than simply storehouses of carbon, complicates decision making and may require shifts in policy. I am all too aware of these challenges. I have spent my entire adult life studying and thinking about the carbon cycle and I too sometimes can't see the forest for the trees. One morning several years ago, I was sitting on the rainforest floor in Costa Rica measuring CO 2 emissions from the soil—a relatively time intensive and solitary process.

As I waited for the measurement to finish, I spotted a strawberry poison dart frog—a tiny, jewel-bright animal the size of my thumb—hopping up the trunk of a nearby tree. Intrigued, I watched her progress towards a small pool of water held in the leaves of a spiky plant, in which a few tadpoles idly swam. Once the frog reached this miniature aquarium, the tiny tadpoles (her children, as it turned out) vibrated excitedly, while their mother deposited unfertilised eggs for them to eat. As I later learned, frogs of this species (Oophaga pumilio) take very diligent care of their offspring and the mother's long journey would be repeated every day until the tadpoles developed into frogs.

It occurred to me, as I packed up my equipment to return to the lab, that thousands of such small dramas were playing out around me in parallel. Forests are so much more than just carbon stores. They are the unknowably complex green webs that bind together the fates of millions of known species, with millions more still waiting to be discovered. To survive and thrive in a future of dramatic global change, we will have to respect that tangled web and our place in it.

Este artículo se ha vuelto a publicar de The Conversation con una licencia de Creative Commons. Lea el artículo original.