Descubriendo costos, riesgos y oportunidades:los investigadores de NREL, incluido el científico Zhe Huang (en la foto), están analizando el potencial técnico y económico de electrificar y descarbonizar la producción de combustibles y productos químicos. Crédito:Werner Slocum, NREL

El petróleo, el carbón y el gas natural no son los únicos puntos de partida para fabricar combustibles y productos químicos. De hecho, los crecientes suministros de electricidad renovable abren nuevas e interesantes puertas para fabricar productos idénticos a una fracción potencial del costo climático.

Comienza con el giro constante de una turbina eólica o un panel solar que se calienta bajo el sol de media tarde. Una corriente fluye a través de una celda electroquímica llena de dióxido de carbono (CO2 )—extraído del aire o capturado de una refinería de etanol, planta de cemento u otra fuente industrial.

Energizado por iones y radicales creados por la carga, el átomo de carbono en el gas se despega de sus vecinos de oxígeno y busca nuevos compañeros con los que unirse. Rápidamente se adhiere a otros carbonos recién liberados, así como a los átomos de hidrógeno que se generan en la célula.

La molécula exacta que el carbono ayuda a formar depende del electrocatalizador en la celda y del voltaje aplicado desde el principio:

Es una reacción electroquímica, una vía emergente para mejorar el CO2 e incluso compuestos derivados de biomasa en los muchos plásticos, detergentes, combustibles y compuestos que sustentan la economía moderna.

Junto con un conjunto más amplio de tecnologías que manejan electricidad renovable para sintetizar productos químicos y combustibles, la tecnología promete ayudar a descarbonizar la industria pesada. Pero, ¿están realmente listos para el mercado?

Sobre los costes, riesgos y oportunidades de electrificar la producción de productos químicos y combustibles

"Esencialmente, estamos hablando de una intersección entre la electrificación y la utilización de materias primas bajas en carbono como el dióxido de carbono y la biomasa", dijo Joshua Schaidle, gerente del programa de laboratorio del Laboratorio Nacional de Energía Renovable (NREL, por sus siglas en inglés) de la Oficina de Energía Fósil y Energía Fósil del Departamento de Energía de EE. UU. Gestión del Carbono. Schaidle también lidera la investigación de transformación catalítica de carbono de NREL y dirige el Consorcio de Catálisis Química para Bioenergía del Departamento de Energía de EE. UU. "Alimentados por energía renovable en lugar de electricidad de origen fósil, estos sistemas podrían permitir que las industrias vayan más allá del carbono fósil".

Según Schaidle y su colega del NREL, Gary Grim, ese método alternativo para fabricar combustibles y productos químicos podría ser una herramienta fundamental para descarbonizar un sector económico que a menudo deja huellas de carbono profundas a su paso.

En lugar de extraer el carbono "fósil" almacenado bajo tierra, estos métodos reciclan el carbono "moderno" que se encuentra en el CO2 o biomasa. Y en lugar de depender de fuentes de energía intensivas en carbono, funcionan con electricidad renovable y sin emisiones. El resultado podría ser un proceso de producción de combustibles y productos químicos significativamente menos intensivo en carbono.

Aún así, quedan muchas preguntas sobre los costos, los riesgos y los desafíos técnicos de fabricar productos químicos y combustibles a partir de electricidad verde y carbono reciclado. "¿Dónde están las tecnologías hoy en día? ¿Dónde podrían estar en el futuro? ¿Y cómo juega un papel en los próximos pasos y las futuras necesidades de investigación?" preguntó Schaidle.

En un par de artículos publicados en Energy and Environmental Science y Cartas de energía de ACS, Schaidle, Grim y sus colegas exploran esas preguntas y otras sobre el potencial técnico y económico de electrificar y descarbonizar la producción de combustibles y productos químicos.

Con mucha incertidumbre restante, esperan que hacer ese trabajo pueda ayudar a marcar el camino a seguir desde la mesa de trabajo del laboratorio hasta el mundo comercial.

Documento 1:La economía de la utilización del dióxido de carbono

Los estudios sugieren que existen tecnologías hoy en día para convertir CO2 en todos los principales productos y productos químicos a base de carbono consumidos a nivel mundial, un mercado actualmente dominado por fuentes fósiles de carbono.

A través de una herramienta de visualización en línea, NREL ofrece información sobre la viabilidad económica y los principales factores de costo de producir productos químicos intermedios a partir de CO2 y electricidad a través de cinco vías de conversión diferentes. Estos incluyen vías que usan electricidad renovable directamente para convertir químicamente el CO2 en productos químicos, así como vías que usan electricidad indirectamente a través de transportadores de electrones intermedios, como el hidrógeno. Crédito:Werner Slocum, NREL

Por ejemplo, cada año se emiten más de 10 gigatoneladas de carbono como CO2 alrededor del mundo. Si se captura y se envía a través de una celda electroquímica, ese CO2 puede convertirse en un suministro de materia prima lo suficientemente grande como para producir más de 40 veces la producción mundial total de etileno y propileno.

En una Energía y Ciencias Ambientales artículo, "Perspectivas económicas para convertir CO2 y electrones a moléculas", los investigadores del NREL Zhe Huang, Schaidle, Grim y Ling Tao analizan la economía del CO2 electroquímico utilización hoy y en el futuro. El documento considera numerosos factores tecnológicos y factores de costo que podrían afectar la viabilidad de producir productos químicos, combustibles y materiales a partir de CO2. y electricidad renovable a escala.

"Tomamos una mirada amplia a través de múltiples tecnologías a múltiples productos", dijo Grim. "El punto clave es que estamos utilizando suposiciones económicas consistentes para nuestro análisis".

According to their study, it could soon be as cost effective to make some of the most widely used chemicals out of CO2 and green electricity as it is to make them using current petroleum-based methods. At the current rate of falling electricity prices and expected improvements in technology, it could even become cheaper in some cases.

"The advancements we are seeing, the activity we are seeing—we will have commercial offerings in the next 5 to 10 years," Schaidle said. "I think there are opportunities to get down to cost competitiveness, especially as you start to consider any low-carbon credits that come along."

To arrive at such conclusions, the study incorporates a broad range of assumptions. It considers energy prices and the cost to build new facilities or install new equipment. It factors in technical and chemical influences that could impact the viability of a technology, such as the speed or efficiency of a certain electrochemical reaction.

Not least, the analysis takes a close look at the impact of CO2 source and concentration on the price to make a given chemical, be it carbon monoxide, ethylene, or a hydrocarbon fuel. Where CO2 siphoned directly from the atmosphere is relatively dilute, for example, capturing it from a power plant or biorefinery yields higher concentrations.

To make it easier to sift through the data behind their analysis, Schaidle, Grim, and their colleagues have published a powerful online visualization tool. It includes interactive charts on the economic feasibility and key cost drivers of producing chemical intermediates from CO2 and electricity across five different conversion pathways.

In this way, the takeaways from the paper become easily accessible for a broad audience. For example, their analysis concludes that carbon monoxide made from CO2 and electricity via high-temperature electrolysis—a specific kind of electrochemical technology—would be relatively expensive by today's standards, at $0.38 per kilogram. Move into the near future, however, and the economics flip. The study projects the price to fall well below today's market price to $0.15 per kilogram.

"Is this a reality? How close can we get on a cost-competitive basis?" reflected Schaidle. "What are the performers or non-performers?"

With the new paper and visualization tool, arriving at answers is easier than ever before.

Paper 2:The status of electrochemical conversion of plentiful biomass

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, biomass resources in the United States could be harnessed to produce up to 50 billion gallons of biofuel each year, more than enough to cover the entire U.S. demand for jet fuel.

But where the carbon in CO2 forms a simple chemical configuration—a gas with one part carbon, two parts oxygen—the renewable carbon in that plentiful biomass is integrated into fibrous networks of lignin and carbohydrates. That makes the starting point for making chemicals with biomass fundamentally different.

Biomass—which includes energy crops, forestry waste, and other organic matter—must first be broken apart into chemical intermediates:polyols, furans, carboxylic acids, amino acids, lignin, and others. Once stored in a more basic form, that renewable carbon can then be more easily accessed, amended, and rearranged.

"You can convert these intermediate molecules thermochemically and biologically, but you can also look at electrochemistry," Schaidle explained. "Our review focuses on the latter piece, where you are looking at converting an intermediate into a product rather than starting with whole biomass."

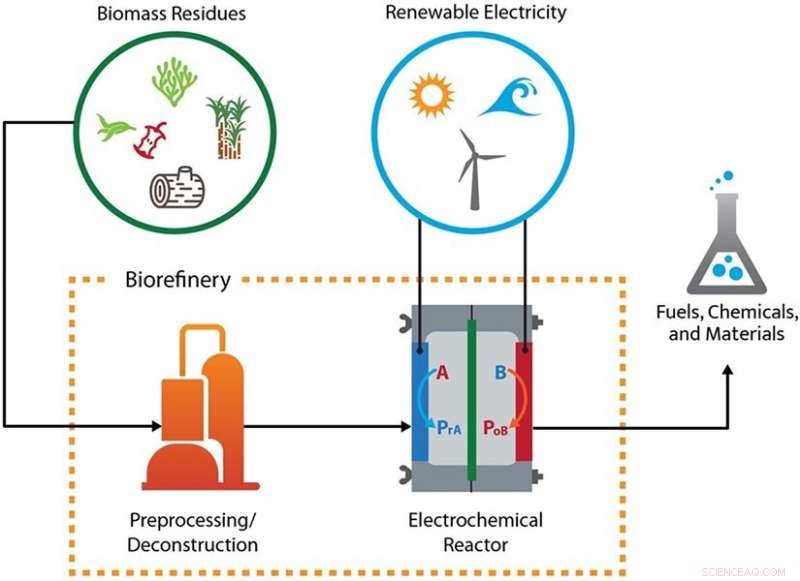

A large number of fuels, chemicals, and materials can be accessed from biomass using renewable electricity. In the electrochemical reactor, “A” and “B” represent biomass-derived compounds that are upgraded by forming either reduction products (blue arrow, PrA) or oxidation products (red arrow, PoB). Credit:National Renewable Energy Laboratory

In a second paper published in ACS Energy Letters , Schaidle, Grim, and a larger team of scientists—including Francisco W.S. Lucas and Adam Holewinski from the University of Colorado, Boulder—analyze over 82 reactions driven by the electrochemical synthesis of biomass intermediates. Those reactions have potential advantages, according to the paper.

"Conventional methods only have heat and pressure as their hammers," Grim explained. "With electrochemistry and biomass intermediates, we have the ability to target specific chemical bonds or groups that can be otherwise difficult to access."

Grim said that could give industries more latitude to invent chemistries otherwise hard to achieve—a potential advantage over conventional, petroleum-based refining. Still, the electrochemical synthesis of biomass intermediates is immature compared to CO2 utilization.

"If you want this technology to get closer to becoming market competitive, you have to have an electrochemical process that is overall more efficient," Schaidle added. "It makes the best utilization of the carbon coming in and the best utilization of the electrons coming in. That is where a lot of the technology advancements need to happen."

By pulling together more than 500 publications on the field—articles often focused on specific reactions using electrochemistry—the paper serves as a roadmap for assessing the state of electrochemistry with biomass-derived intermediates and finding the best entry points for improving the technology. With this broad analysis, the team of scientists aims to foster more focus and intentionality in future research.

"This is cross-cutting analysis to help people move forward," Schaidle added. "We are synthesizing all the science to give a clear blueprint for strategic research."

Slow but steady:Steps to decarbonizing chemical manufacturing

Schaidle and Grim are honest about the challenges ahead. After all, should we even try to electrify biomass conversion? Why convert CO2 and not just capture it and put it underground?

"The short answer is that there are a lot of challenges," Grim said. "Petroleum- and fossil-based processes have had nearly a century head-start on some of these emerging technologies. Those systems are highly optimized, very well studied—and hydrocarbons have a lot of energy already built in."

With no energy content whatsoever, CO2 must be pumped with massive amounts of cheap, clean energy to successfully transform it into something usable. Many electrochemical technologies for converting biomass intermediates have yet to be scaled beyond the lab—an essential step for demonstrating the stability, efficiency, and affordability of any bioenergy technology. Not least, robust supply chains of renewable electrons, CO2 , and biomass are only just emerging.

"The jury is still out:Is this the best use of that abundant future electricity?" Grim asked. "We are still working to understand if these technologies are the best solution for addressing a lot of our climate issues."

Despite the challenges, Schaidle and Grim remain optimistic that these technologies can play a critical role in decarbonizing fuel and chemical manufacturing.

Supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Bioenergy Technologies Office, ARPA-E, and other energy programs, a range of targeted research projects are already helping push down the cost and increase the efficacy of such technologies. One NREL-led team, for instance, is exploring how to use electrochemistry to enable biorefineries to recycle waste CO2 —increasing fuel yields by as much as 40% and decarbonizing the production of ethanol, as well as lipids.

With a nudge in the right direction, more breakthrough projects could be on the horizon.

"How do we guide this field to collectively accelerate everyone's work?" Schaidle said. "That's what we wanted to do—to take this blob of an amoeba and turn it into a foundational first step for people to build off of."

By gathering all the available data—standardizing it, making it comprehensible, giving it form—they hope they can collapse the timeline for improving the technologies. And with deadlines looming for making meaningful progress to lower climate-warming emissions, accelerating R&D could be just what is needed to start eliminating the weighty carbon footprint of making fuels and chemicals.