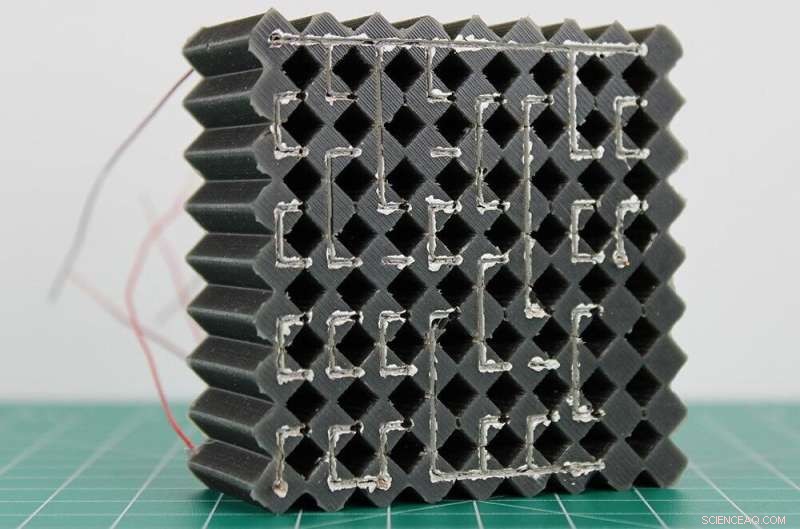

Un material de circuito integrado mecánico puede realizar tareas computacionales como una computadora sin necesidad de la computadora. Aquí, el material de ejemplo realiza operaciones aritméticas, compara números y convierte la información digital en formato de pantalla LED. Crédito:Charles El Helou/Penn State

Alguien toca tu hombro. Los receptores táctiles organizados en tu piel envían un mensaje a tu cerebro, que procesa la información y te indica que mires a la izquierda, en la dirección del toque. Ahora, investigadores de Penn State y de la Fuerza Aérea de EE. UU. han aprovechado este procesamiento de información mecánica y la han integrado en materiales de ingeniería que "piensan".

El trabajo, publicado hoy en Nature , depende de una alternativa novedosa y reconfigurable a los circuitos integrados. Los circuitos integrados generalmente se componen de múltiples componentes electrónicos alojados en un solo material semiconductor, generalmente silicio, y ejecutan todo tipo de dispositivos electrónicos modernos, incluidos teléfonos, automóviles y robots. Los circuitos integrados son la realización de los científicos del procesamiento de información similar al papel del cerebro en el cuerpo humano. Según el investigador principal Ryan Harne, profesor asociado de ingeniería mecánica James F. Will Career Development en Penn State, los circuitos integrados son el componente central necesario para la computación escalable de señales e información, pero los científicos nunca antes los habían realizado en cualquier composición que no sea de silicio. semiconductores

El descubrimiento de su equipo reveló la oportunidad de que casi cualquier material que nos rodea actúe como su propio circuito integrado:poder "pensar" sobre lo que sucede a su alrededor.

"Hemos creado el primer ejemplo de un material de ingeniería que puede sentir, pensar y actuar simultáneamente sobre el estrés mecánico sin requerir circuitos adicionales para procesar tales señales", dijo Harne. "El material de polímero blando actúa como un cerebro que puede recibir cadenas digitales de información que luego se procesan, lo que da como resultado nuevas secuencias de información digital que pueden controlar las reacciones".

El material mecánico suave y conductor contiene circuitos reconfigurables que pueden realizar una lógica combinacional:cuando el material recibe estímulos externos, traduce la entrada en información eléctrica que luego se procesa para crear señales de salida. El material podría usar la fuerza mecánica para calcular aritmética compleja, como demostraron Harne y su equipo, o detectar frecuencias de radio para comunicar señales de luz específicas, entre otros posibles ejemplos de traducción. Las posibilidades son amplias, dijo Harne, porque los circuitos integrados se pueden programar para hacer mucho.

"Descubrimos cómo usar las matemáticas y la cinemática, cómo se mueven los componentes individuales de un sistema, en redes mecánico-eléctricas", dijo Harne. "Esto nos permitió realizar una forma fundamental de inteligencia en materiales de ingeniería al facilitar el procesamiento de información totalmente escalable intrínseco al sistema de materiales blandos".

Los materiales de circuitos integrados mecánicos hechos de materiales de caucho conductores y no conductores detectan y reaccionan a cómo se les aplican las fuerzas. Crédito:Charles El Helou/Penn State

According to Harne, the material uses a similar "thinking" process as humans and has potential applications in autonomous search-and-rescue systems, in infrastructure repairs and even in bio-hybrid materials that can identify, isolate and neutralize airborne pathogens.

"What makes humans smart is our means to observe and think about information we receive through our senses, reflecting on the relationship between that information and how we can react," Harne said.

While our reactions may seem automatic, the process requires nerves in the body to digitize the sensory information so that electrical signals can travel to the brain. The brain receives this informational sequence, assesses it and tells the body to react accordingly.

For materials to process and think about information in a similar way, they must perform the same intricate internal calculations, Harne said. When the researchers subject their engineered material to mechanical information—applied force that deforms the material—it digitizes the information to signals that its electrical network can advance and assess.

The process builds on the team's previous work developing a soft, mechanical metamaterial that could "think" about how forces are applied to it and respond via programmed reactions, detailed in Nature Communications last year. This earlier material was limited to only logic gates operating on binary input-output signals, according to Harne, and had no way to compute high-level logical operations that are central to integrated circuits.

The researchers were stuck, until they rediscovered a 1938 paper published by Claude E. Shannon, who later became known as the "father of information theory." Shannon described a way to create an integrated circuit by constructing mechanical-electrical switching networks that follow the laws of Boolean mathematics—the same binary logic gates Harne used previously.

"Ultimately, the semi-conductor industry did not adopt this method of making integrated circuits in the 1960s, opting instead to use a direct-assembly approach," Harne said. "Shannon's mathematically grounded design philosophy was lost to the sands of time, so, when we read the paper, we were astounded that our preliminary work exactly realized Shannon's vision."

However, Shannon's work was hypothetical, produced nearly 30 years before integrated circuits were developed, and did not address how to scale the networks.

"We made considerable modifications to Shannon's design philosophy in order for our mechanical-electrical networks to comply to the reality of integrated circuit assembly rules," Harne said. "We leapt off our core logic gate design philosophy from the 2021 research and fully synchronized the design principles to those articulated by Shannon to ultimately yield mechanical integrated circuit materials—the effective brain of artificial matter."

The researchers are now evolving the material to process visual information like it does physical signals.

"We are currently translating this to a means of 'seeing' to augment the sense of 'touching' we have presently created," Harne said. "Our goal is to develop a material that demonstrates autonomous navigation through an environment by seeing signs, following them and maneuvering out of the way of adverse mechanical force, such as something stepping on it."

Other authors of the paper include Charles El Helou, doctoral student in mechanical engineering at Penn State, and Benjamin Grossman, Christopher E. Tabor and Philip R. Buskohl from the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory. A future of helpful engineered 'living' machines?