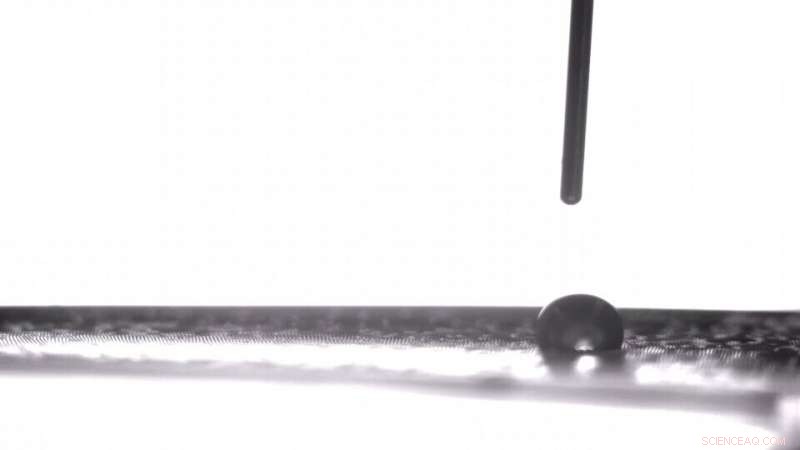

Una gota microscópica de agua que se deposita sobre una película de silicona elástica. Al estirar y relajar sus películas especialmente diseñadas, Los químicos de Nebraska Stephen Morin y Ali Mazaltarim han demostrado un control sin precedentes sobre el movimiento de las gotas de líquido en superficies planas. Ese control podría hacer que la técnica sea útil en materiales autolimpiantes, recolección de agua y otras aplicaciones. Crédito:Stephen Morin / Ali Mazaltarim

Una minúscula gota de agua se mueve ganando velocidad a medida que se desliza a lo largo de un tramo de delgada, terreno plano. Abruptamente, golpea un terreno accidentado, el equivalente microscópico de los golpes de velocidad de vidrio en los que la gota se asienta y se detiene en seco.

La gota aparece estacionada, anclado en su lugar. Pero a diferencia de sus contrapartes macro, estos mini topes de velocidad se aplanan fácilmente. Stephen Morin lo sabría; supervisó su construcción. Entonces, el químico de la Universidad de Nebraska-Lincoln procede a estirar el material elástico sobre el que se sientan, allanando el camino, y se va la gota de nuevo, lanzándose a través de la superficie perfectamente horizontal.

La hazaña de parar y arrancar es solo una de varias que el Grupo Morin ha presentado a través de su última combinación de química y polímeros elásticos. ¿Los frutos de ese matrimonio? Control sin precedentes sobre el transporte de gotitas microscópicas, potencialmente produciendo nuevos enfoques para materiales autolimpiantes, técnicas de recolección de agua y otras, tecnologías más sofisticadas.

El concepto de humectabilidad es fundamental para el enfoque del equipo, ya sea que una gota gotee o se extienda sobre una superficie, revelando esa superficie como hidrofóbica o hidrofílica, respectivamente. Inspirado por algunas investigaciones pioneras de principios de la década de 1990, Morin y su laboratorio comenzaron a crear gradientes de humectabilidad:superficies cubiertas por diminutas "rampas" químicas que las hacen hidrófobas en un extremo pero hidrófilas en el otro.

"Resulta que si tienes un patrón químico como ese, cuando coloca una gota en el extremo hidrofóbico, este gradiente de humectabilidad conducirá la gota hacia el lado hidrófilo de forma espontánea, "dijo Morin, profesor asociado de química en Nebraska.

Aunque es un fenómeno interesante por derecho propio, Morin y el candidato a doctorado Ali Mazaltarim querían ver si podían adaptar ese transporte pasivo en un activo, proceso dinámico que se prestaría mejor a las aplicaciones. Recurrieron al tipo de materiales elásticos que el equipo de Morin ha estado recubriendo con patrones químicos desde 2015, ya sea para crear superficies que reflejen la luz solo cuando se estiran o filtrar partículas según la forma.

Como lo había hecho a menudo en el pasado, el equipo empezó con un suave, película de silicona flexible. Los investigadores estiraron esa película antes de tratarla con ozono ultravioleta para producir una capa microscópicamente delgada de sílice. el componente principal de la mayoría de los vidrios. Luego recubrieron ciertas secciones de la sílice con densos matorrales de moléculas repelentes al agua; otras secciones se dejaron en su mayor parte o completamente desnudas, creando un gradiente de humectabilidad que podría conducir las gotas de lo hidrófobo a lo hidrófilo.

Conseguir algo de control en tiempo real sobre el movimiento de esas gotas era entonces una cuestión simple y literal de dejarse llevar. Relajar la película de silicona preestirada introdujo arrugas en la sílice, similar a cómo una curita colocada sobre el codo de un brazo doblado se arrugará cuando se estire el brazo. El equipo de Morin sospechaba que esas arrugas podrían introducir suficiente aspereza para ralentizar la velocidad de las gotas. incluso en los tramos hidrofóbicos de la superficie.

Los experimentos confirmaron la hipótesis:en su forma completamente relajada, estado arrugado, los estiramientos hidrofóbicos podrían detener las gotas por completo; en su total tensión, estado suave, transportaron las gotas como lo harían normalmente.

Desde entonces, los investigadores han perfeccionado ese control estirando y relajando las películas para iniciar y detener las gotas segundo a segundo. Incluso han demostrado la capacidad de desafiar la gravedad, transporte de gotas en pendientes más pronunciadas que las informadas en investigaciones anteriores.

Jinetes rudos

Si, y que tan rápido, a droplet will move depends in part on the severity of a wettability gradient. When the transition from hydrophobic to hydrophilic occurs over a short distance, the droplets speed across the surface; when that transition stretches over a longer distance, the droplets lumber at a slower pace. The "steeper" the gradient, en otras palabras, the greater the driving force and velocity of the droplets. Otros factores, including droplet size, are well-known contributors, también.

But the team was also finding that its acceleration and braking systems depended not just on the presence of the microscopic speed bumps, but also their height and spacing, both of which seemed to be influencing droplet velocity. From a mathematical and theoretical standpoint, the team realized, the roughness of the surface wasn't getting its due.

To better understand and predict how roughness was affecting droplet transport, Morin and Mazaltarim incorporated the variable into a couple of equations that are traditionally used to quantify the phenomenon. After some tweaking and experimental verification, their resulting model predicted the specific roughness needed to slow or stop a droplet of any given size—along with the minimum size needed to overcome that roughness and other factors that resist a droplet's movement.

Ese, Sucesivamente, allowed the team to craft surfaces that would transport larger droplets while leaving smaller ones in place, or trigger the departure of the latter only when stretching the elastic film beyond a certain threshold. Y eso, the team said, could prove useful in sorting different liquids for analytical or other purposes.

The ability of such a simple technique to yield such precise, predictable behavior makes it promising for a range of other applications, Morin said. The team has already illustrated its potential in self-cleaning materials by dirtying an elastic surface with metal dust, then stretching it to trigger a cascade of droplets that carried away all dust in their path. The harvesting of water for urban agriculture, livestock or potable water might benefit from a similar approach.

"You could imagine fabrics where you collect droplets at one section, " Morin said, "and then you actuate the surface, which then drives them to some sort of a storage container."

There's also the possibility of expanding on the functionality of materials that are designed to remove sweat from skin or droplets from other surfaces. The latter could potentially help cool energy-generating systems that produce sizable amounts of heat.

"A lot of research in that area focuses on hydrophobic and superhydrophobic surfaces that have unique heat-exchange properties, " Morin said. "One could use the evaporative cooling effect of sweat as inspiration. But we imagine a more active system, where you're literally using a droplet to collect heat and then actively moving it somewhere else to remove that heat.

"That's a good thing if you're actively trying to cool any sort of a device. This just presents a new way of achieving that type of outcome."

Further down the line, Morin sees promise for calibrating the technique to transport droplets in two dimensions rather than just one. Managing that, él dijo, could make it a viable alternative in so-called lab-on-a-chip technologies that direct, mix and then analyze microscopic samples of liquids.

"We have the ability to really dial in the properties of the gradients and how they couple to the micro-texture of the surface, " Morin said. "So I think there's a lot of leeway in terms of how you design the system to get a specific performance outcome."

The team reported its findings in the journal Comunicaciones de la naturaleza .