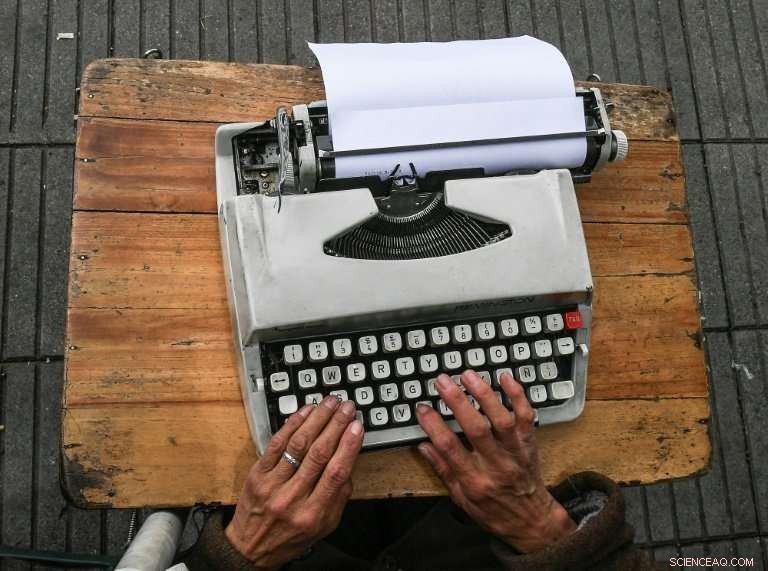

Los empleados de la calle de Colombia trabajan al aire libre con sus máquinas de escribir colocadas en una pequeña mesa frente a ellos.

Antes del Primero de Mayo, Reporteros de AFP, equipos de video y fotografía hablaron con hombres y mujeres de todo el mundo cuyos trabajos son cada vez más raros, particularmente a medida que la tecnología transforma las sociedades.

Los últimos empleados de la calle de Bogotá

Insertando una hoja en blanco en su Remington Sperry, Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez empieza a escribir. Uno de los empleados de la calle de Bogotá, ha pasado los últimos 40 años mecanografiando incontables miles de documentos.

63 años, ella es la única mujer entre los empleados de la calle que han instalado sus mesitas en la acera frente a un moderno edificio de oficinas en Bogotá.

Vistiendo trajes pero sin corbatas, los escritores trabajan al aire libre, bajo una sombrilla, sentados en una silla de plástico con la máquina de escribir de rodillas.

Había una vez, Estos empleados desempeñaron un papel esencial:con escrituras públicas, documentos fiscales y contratos que pasan por sus manos.

Pinilla de Gómez aprendió el oficio de su esposo cuando llegaron a la capital colombiana en la década de 1960. Tenía una finca "pero la guerrilla se la quitó, " ella dice.

"En Bogotá, me dijo que debería aprender a escribir ... y a deletrear. Me enseñó (el trabajo) y luego murió ".

Cesar Diaz, ahora 68, se enorgullece de ser el pionero de un oficio que se ha convertido en un "refugio" para los pensionistas que buscan completar sus asignaciones mensuales.

Candelaria Pinilla de Gómez, 63, trabaja como empleado de calle en Bogotá desde hace unos 40 años

Trabajan de lunes a viernes y ganan menos de $ 280 que es el salario mínimo.

Hasta ahora, se las han arreglado para sobrevivir a casi todo, excepto quizás a la llegada de Internet.

"Estos días, una madre le pedirá a su hijo que descargue un formulario, rellénelo y envíelo por internet, "admite Pinilla de Gómez.

"Eso realmente nos arruina las cosas".

- Imágenes de Luis Acosta. Video de Juan Restrepo

Lavanderas su oficio desapareciendo como jabón en agua

Las manos de Delia Veloz casi pierden sus huellas dactilares por el constante movimiento rítmico de frotar ropa sucia contra piedras en bruto en una vieja lavandería pública en Quito.

Con una fregona de rizos grises y rizados, esta mujer de 74 años es una de las pocas personas que quedan en Ecuador que aún practica el antiguo y exigente trabajo de lavandera, oficio cada vez más raro debido al uso generalizado de las lavadoras domésticas.

Wu Chi-kai dobla tubos de vidrio espolvoreados por dentro con polvo fluorescente en forma sobre un potente quemador de gas

"No me gustan las lavadoras, no se lavan muy bien. Puedes restregar mejor las cosas a mano, Veloz le dice a AFP con orgullo mientras vierte una jarra de agua helada de los Andes sobre una chaqueta.

Desde hace más de cinco décadas trabaja en la Ermita, un lavadero público en el centro colonial de Quito con su piedra rectangular, tanque de agua y varios cables para colgar las cosas para que se sequen.

Por cada 12 prendas de vestir, gana 1,50 dólares (1,20 euros) de sus cada vez más escasos clientes, sobre todo aquellos que no tienen lavadora o que prefieren que las cosas se laven a mano.

En un buen dia, ella puede ganar entre $ 3 y $ 6.

En Quito, todavía hay al menos cinco lavanderías públicas que se construyeron en la primera mitad del siglo XX.

También están los que vienen a usar la lavandería para lavar su propia ropa o la de sus empleadores, por lo que no hay tarifa.

Y una vez al mes todos se reúnen para mantener el local limpio y ordenado.

- Fotografías de Rodrigo Buendia

El neón ha llegado a definir el paisaje urbano de Hong Kong, con enormes letreros intermitentes que sobresalen horizontalmente de los lados de los edificios

Waterboys comienza a secarse

La falta de agua corriente en los barrios más pobres de Kenia ha durante los últimos 18 años, significó una vida para Samson Muli, un vendedor de agua en el barrio pobre de Kibera en Nairobi.

"Al crecer, quería ser un hombre de negocios, "dice el padre de dos hijos de 42 años, que abastece de agua a los carniceros, pescaderías y restaurantes en el concurrido mercado de Kenyatta.

Vestido con un abrigo pardo, Muli usa una manguera para llenar su variedad de bidones cilíndricos de 20 litros con agua de tres 10 independientes, Depósitos de 000 litros. Carga 15 a la vez en un carrito, y se los lleva a sus clientes.

Los márgenes son pequeños:Muli compra agua a cinco chelines ($ 0.05) la lata y la vende a 15, pero puede sumar 1, 000 chelines al día, lo suficiente para marcar la diferencia.

"Este trabajo ha cambiado mi vida porque mis hijos pueden ir a la escuela y yo puedo pagar la matrícula escolar por ellos, " él dice.

Pero el desarrollo gradual de Kenia y la provisión cada vez mayor de infraestructura básica, incluyendo agua corriente, significa que los rentables días de Muli están contados.

— Pictures by Simon Maina. Video by Raphael Ambasu

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes

Rickshaw pullers fade from India's streets

Mohammad Maqbool Ansari puffs and sweats as he pulls his rickshaw through Kolkata's teeming streets, a veteran of a gruelling trade long outlawed in most parts of the world and slowly fading from India too.

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life, but Ansari is among a dying breed still eking a living from this back-breaking labour.

The 62-year-old has been pulling rickshaws for nearly four decades, hauling cargo and passengers by hand in drenching monsoon rains and stifling heat that envelops India's heaving eastern metropolis.

Their numbers are declining as pulled rickshaws are relegated to history, usurped by tuk tuks, Kolkata's famous yellow taxis and modern conveniences like Uber.

Ansari cannot imagine life for Kolkata's thousands of rickshaw-wallahs if the job ceased to exist.

"If we don't do it, how will we survive? We can't read or write. We can't do any other work. Once you start, eso es todo. This is our life, ", le dice a la AFP.

Sweating profusely on a searing-hot day, his singlet soaked and face dripping, Ansari skilfully weaved his rickshaw through crowded markets and bumper to bumper traffic.

Venezuelan darkroom technician Rodrigo Benavides refuses to go digital

Wearing simple shoes and a chequered sarong, the only real giveaway of his age is a long beard, snow white and frizzy, and a face weathered from a lifetime plying this trade.

Twenty minutes later, he stops, wiping his face on a rag. The passenger offers him a glass of water—a rare blessing—and hands a bill over.

"When it's hot, for a trip that costs 50 rupees ($0.75) I'll ask for an extra 10 rupees. Some will give, algunos no " él dice.

"But I'm happy with being a rickshaw puller. I'm able to feed myself and my family."

— Pictures by Dibyangshu Sarkar. Video by Atish Patel

Hong Kong's neon nostalgia

Neon sign maker Wu Chi-kai is one of the last remaining craftsmen of his kind in Hong Kong, a city where darkness never really falls thanks to the 24-hour glow of myriad lights.

During his 30 years in the business, neon came to define the urban landscape, huge flashing signs protruding horizontally from the sides of buildings, advertising everything from restaurants to mahjong parlours.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography does not exist

But with the growing popularity of brighter LED lights, seen as easier to maintain and more environmentally friendly, and government orders to remove some vintage signs deemed dangerous, the demand for specialists like Chi-kai has dimmed.

Despite a waning client-base, the 50-year-old continues in the trade, working with glass tubes dusted inside with fluorescent powder and containing various gases including neon or argon, as well as mercury, to create different colours.

He bends them into shape over a powerful gas burner at a scorching 1, 000 degrees Celsius.

"Being able to twist straight glass materials into the shape I want, and later to make it glow—it's quite fun, "le dice a la AFP, though it is not without risks.

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes.

"The painful experiences are the memorable ones, " he adds philosophically.

His father used to scale Hong Kong's famous bamboo scaffolding while installing neon signs across the city.

Believing the installation work too dangerous for his son, he instead encouraged him to learn to make the signs as a teenager. Chi-kai became one of only around 30 masters of the craft in Hong Kong, even in neon's heyday.

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints

Although demand is now significantly lower than at neon's peak in the 1980s, él dice, there has been renewed interest and nostalgia for its gentler glow, immortalised in the atmospheric movies of award-winning Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai.

Some of Chi-kai's clients are now requesting pieces for indoor decoration.

"I've been working with neon lights all my life. I can't think of anything else I'd be better suited for, " él dice.

— Pictures by Philip Fong. Video by Diana Chan

Developing film as if digital didn't exist

With an ancient 50-year-old Olympus camera and an enlarger that he bought in 1980, Venezuelan photographer Rodrigo Benavides works his "magic" inside a tiny improvised darkroom at home.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography doesn't exist.

"Doesn't interest me at all, " él dice.

Había una vez, these clerks played an essential role—with public deeds, tax documents and contracts all passing through their hands

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints. And it still fascinates him every time as the image slowly emerges on coming in to contact with the chemicals.

"I have always tried to be economical with my resources, always have done, always will do, " he says, extolling the wonders of his Olympus 35 SP which uses a reel of film, doesn't need batteries and is completely manual.

Born in Caracas 58 years ago, he still remembers the excitement when, at the age of 19, he bought the enlarger in London.

And it was there that he became a keen follower of Group f/64, an influential movement of photographers who championed sharp-focused, unretouched images of natural subjects.

He thinks technology has "upended" photography, turning it into a work of "fiction."

"We have become desensitised to reality, which is much more interesting than fiction, " él dice.

Some 400 of his pictures taken over 30 years have been compiled into a book on the Venezuelan plains. Others are stacked up in his living room, forming a towering pile, some two meters high.

"They are like my children, " says Benavides, who describes himself as a documentary photographer practising a trade on the verge of extinction.

Delia Veloz, 74, is one of the few people left in Ecuador who still practises the ancient and demanding work of a washerwoman

Washerwomen rub dirty clothes against rough stones at an old public laundry in Quito

In Quito, there are still at least five public laundries which were built in the first half of the 20th century

The lack of running water in Kenya's poorest neighbourhoods has meant a living for Samson Muli, a water seller in Nairobi's Kibera slum

Waterboys supply water to butchers, fishmongers and restaurants in the crowded Kenyatta market

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life

Mohammad Ashgar is one of the remaining Indian rickshaw pullers undertaking the gruelling trade

© 2018 AFP