Crédito:Wikipedia

La glicoproteína espiga homotrimérica (S) del SARS-CoV-2, en particular su subunidad S2, es una proteína de fusión extraordinaria. Puede fusionar partículas virales con células y también fusionar células con células para crear múltiples sincitios entre diferentes fenotipos celulares. Dependiendo de las versiones exactas que se estén considerando, el pico puede realizar estas hazañas a través de múltiples mecanismos que actúan tanto en el lado intracelular como en el extracelular de las membranas celulares.

Estas funciones de fusión son algo análogas a las proteínas ENV homotriméricas típicas (envoltura) como nuestra proteína ENV retroviral endógena sincitina-1 y la glicoproteína ENV GP160 del virus del VIH. GP160, la proteína "espiga" del VIH, finalmente se procesa en su propio sitio de escisión de furina (que también se encuentra en la sincitina-1) en una proteína GP120 y GP41, las cuales pueden adoptar distintas configuraciones previas y posteriores a la fusión. Sin embargo, el genoma del SARS-CoV-2 ya especifica una pequeña proteína ENV separada (convenientemente designada como E), que se ensambla en un presunto canal catiónico con un poro de fusión central.

No hay genes env, pol, gag o pro definidos como tales para el genoma del SARS-CoV-2, como es el caso de los retrovirus, que deben integrarse a nuestro ADN como parte de su ciclo de vida. Curiosamente, los investigadores han descubierto que la proteína espiga del SARS-CoV-2, comportándose por sí sola, participa directamente en la activación de los retrovirus endógenos en nuestras células, lo que contribuye a la patología observada. Qué está pasando aquí?

A la luz de algunas de estas similitudes, se ha sugerido que los anticuerpos generados contra la proteína espiga podrían reaccionar de forma cruzada en cualquier tejido que pudiera expresar proteínas retrovirales endógenas. En particular, durante el embarazo, después de lo cual los trofoblastos placentarios expresan proteínas ENV muy útiles de muchos de estos HERV, incluidos ERVW1 (sincitina-1), ERVFRD-1 (sincitina-2), ERVV-1, ERVV-2, ERVH48-1, ERVMER34-1 , ERV3-1 y ERVK13-1. Sin embargo, la expresión de sincitina-2 en los citotrofoblastos vellosos está altamente correlacionada con el grado de gravedad de alguna patología placentaria como la preeclampsia.

Afortunadamente, los investigadores descubrieron que prácticamente no existe una homología de secuencia directa entre la espiga y la sincitina-1, y hay pocas posibilidades de reactividad cruzada. Escrito en la revista Animal Cells and Systems , los investigadores coreanos probaron un gran panel de anticuerpos monoclonales y pudieron concluir que, si bien el SARS-CoV-2 puede activar reliquias genómicas antiguas como los HERV en varios tejidos, no existe riesgo de reactividad cruzada o incluso infertilidad.

Pero si la proteína espiga sigue siendo muy capaz de causar una fusión celular indeseable, ¿cómo podemos definir mejor esta actividad aparentemente aleatoria y, además, qué podemos hacer al respecto? Quizás el primer paso sea volverse un poco más sofisticado con la terminología de fusión celular. Escribir en el diario Oncotarget , el autor Yuri Lazebnik ofrece algo de reflexión. Un sincitio producido a partir de células del mismo tipo, por ejemplo, como en la fusión de dos o más neumocitos, se denomina homocarión. Entonces, un heterocarión sería un sincitio hecho de, digamos, un neumocito fusionado con un progenitor epitelial, o quizás un leucocito. En general, una vez que las células se combinan, todas las apuestas están canceladas:aún no se sabe por completo si pueden clasificarse a sí mismas y sus núcleos para generar descendencia mononuclear competente para la replicación.

Formation of spike-induced syncytia in the lungs of COVID-10 patients has been found in many forms, each with their own emergent properties that can contribute to disease sequelae. For example, ciliated cells in the airway, alveolar type 2 pneumocytes, and epithelial progenitors have all been found to participate in the oft-observed multinucleated 'giant cells.' Throw in a spike-laden leukocyte or two and things rapidly get hard to predict. Perhaps an even more alarming situation would be formation of a syncytium in the cells lining our blood vessels that could contribute to thrombosis. The ensuing death and eventual sloughing off of a patch of inappropriately fused cells could expose a sizeable region of thrombogenic basement membrane. A 20-micron fiber of collagen, the main component of the basement membrane, is sufficient to trigger platelet-dependent clotting.

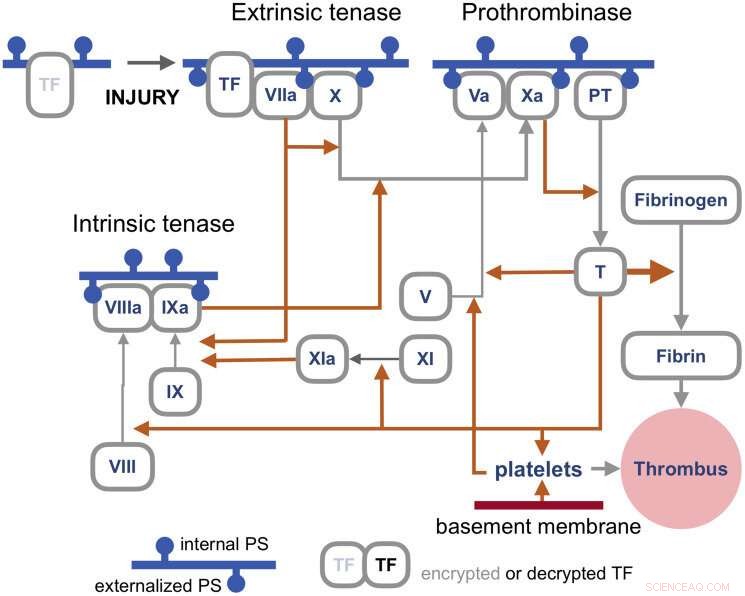

But enough of this fear-mongering. Researchers have identified a set of already approved drugs that prevent spike-induced cell fusion and inhibit TMEM16F, a critical protein for syncytium formation. TMEM16F has the dual role of being a calcium-activated ion channel that regulates chloride secretion, as well as a lipid scramblase that relocates phosphatidylserine (PS) to the cell surface. This PS externalization is required for cell fusion in many systems, including spike-induced syncytia. Incidentally, scramblases also control the rate-limiting steps of the blood coagulation cascade, and may be the mechanism behind spike-induced thrombosis.

The blood coagulation pathways are a whole separate complex can of worms, but suffice it to say here that the primary trigger of coagulation induced by viral infections is the so-called extrinsic 'tenase.' Tenases are enzymes that process Factor X, or FX, (hence ten-ase), in the Tissue Factor (TF) activation pathway, which essentially act as the fuse for thrombus generation. The resulting complexes are assembled on externalized PS in the presence of calcium ions. TF is, in a sense, encrypted and so is unable to activate its downstream target factor FVIIa until it is de-encrypted by externalized PS.

Coagulation pathways. Credit:Y. Lazebnik 2021

The realization that some fusogenic viral, or even retroviral proteins, which are fortuitously expressed in particular regions of the body may likely contribute to thrombotic events is of tremendous practical importance. One need look no further than Moderna's ample proposed pipeline for therapeutic mRNA-delivered amenities based on these proteins for all manner of viral insults to have some pause for inspection. There is certainly no shortage of methods currently employed for building antigenic spike proteins for vaccinations. Depending of how much of the spike code is used, which cleavage sequences are included, and which parts are stabilized, very different proteins can be made. It is probably fair to say that full-length spikes in large questionable vectors or inactivated viral particles have been largely de-emphasized in favor of smaller but more immunogenic concoctions.

Lungs and blood vessels are certainly critical areas of concern in any SARS-CoV-2 infection, but what our precious neurons—can spike fuse them as well? Clearly it can fuse neurons in brain organoids, but then again, what can't researchers do with these instant research publication miracles. In looking more braodly at other kinds of viruses, the fusion of neurons, glial cells, and even axons seems to be par for the course in causing a myriad constellation of potential neurological issues. For example, the pseudorabies virus bridges synapses to electrically couple the activity of neurons by fusing their axons. Fusions with glia have similarly been detected and linked with lasting neuropathic pain after the acute phase of herpes zoster (shingles). As of this Wednesday, we all are further aware that SARS-CoV-2 can utilize the protein vimentin as a way to infect endothelial cells. It should escape no one's notice, or at least that of the neuroscientists, that vimentin is the prime marker used for identifying glial cells.

Additionally, the rapidly expanding body of work looking at endogenous retrovirus re-activation in neurodegenerative disease further suggests to the rational mind that cell fusion may also be involved in this kind of pathology.