¿Cómo pueden saber los investigadores si los dinosaurios machos y hembras, como el estegosaurio, eran diferentes? Crédito:Susannah Maidment et al. y Museo de Historia Natural, Londres, CC BY

En la mayoría de las especies animales, los machos y las hembras difieren. Esto es cierto para las personas y otros mamíferos, así como para muchas especies de aves, peces y reptiles. Pero, ¿y los dinosaurios? En 2015, propuse que la variación encontrada en las icónicas placas traseras de los dinosaurios estegosaurios se debía a las diferencias de sexo.

Me sorprendió lo mucho que discrepaban algunos de mis colegas, argumentando que las diferencias entre sexos, llamadas dimorfismo sexual, no existían en los dinosaurios.

Soy paleontólogo, y el debate provocado por mi artículo de 2015 me ha hecho reconsiderar cómo los investigadores que estudian animales antiguos usan las estadísticas.

El registro fósil limitado hace que sea difícil declarar si un dinosaurio era sexualmente dimórfico. Pero yo y algunos otros en mi campo estamos comenzando a alejarnos del pensamiento estadístico tradicional de blanco o negro que se basa en los valores p y la significación estadística para definir un hallazgo verdadero. En lugar de solo buscar respuestas de sí o no, estamos comenzando a considerar la magnitud estimada de la variación sexual en una especie, el grado de incertidumbre en esa estimación y cómo se comparan estas medidas con otras especies. Este enfoque ofrece un análisis más matizado de preguntas desafiantes en paleontología, así como en muchos otros campos de la ciencia.

Diferencias entre hombres y mujeres

El dimorfismo sexual es cuando los machos y las hembras de una determinada especie difieren en promedio en un rasgo particular, sin incluir su anatomía reproductiva. Los ejemplos clásicos son cómo los ciervos machos tienen cuernos y los pavos reales machos tienen llamativas plumas en la cola, mientras que las hembras carecen de estos rasgos.

El dimorfismo también puede ser sutil y poco llamativo. A menudo, la diferencia es de grado, como las diferencias en el tamaño corporal promedio entre machos y hembras, como en los gorilas. En estos casos modestos, los investigadores usan estadísticas para determinar si un rasgo difiere en promedio entre hombres y mujeres.

En muchas especies, como estos patos mandarines, los machos (izquierda) y las hembras (derecha) se ven muy diferentes. Crédito:Francis C. Franklin vía WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA

El dilema de los dinosaurios

El estudio del dimorfismo sexual en animales extintos está lleno de incertidumbre. Si usted y yo desenterramos de forma independiente fósiles similares de la misma especie, inevitablemente serán ligeramente diferentes. Estas diferencias podrían deberse al sexo, pero también podrían deberse a la edad:las aves jóvenes son peludas, las aves adultas son elegantes. También podrían deberse a una genética no relacionada con el sexo, como el color de los ojos en los humanos.

If paleontologists had thousands of fossils to study of every species, the many sources of biological variation wouldn't matter as much. Unfortunately, the ravages of time have left the fossil record painfully incomplete, often with less than a dozen good specimens for large, extinct vertebrate species. Additionally, there is currently no way to identify the sex of an individual fossil except in rare cases where obvious clues exist, like eggs preserved within the body cavity.

So where does all this leave the debate on whether male and female dinosaurs had differences within traits? On the one hand, birds—which are direct descendants of dinosaurs—commonly show sexual dimorphism. So do crocodilians, dinosaurs' next closest living relatives. Evolutionary theory also predicts that, since dinosaurs reproduced with sperm and egg, there would be a benefit to sexual dimorphism.

These things all suggest that dinosaurs likely were sexually dimorphic. But in science you need to be quantitative. The challenge is that there is little in the way of statistically significant analyses of the fossil record to support dimorphism.

It’s possible that variation among individual dinosaurs of the same species could be due to sexual dimorphism, but there are rarely good enough samples to assert so using traditional statistics. Credit:James Ormiston, CC BY-ND

Statistical shifts

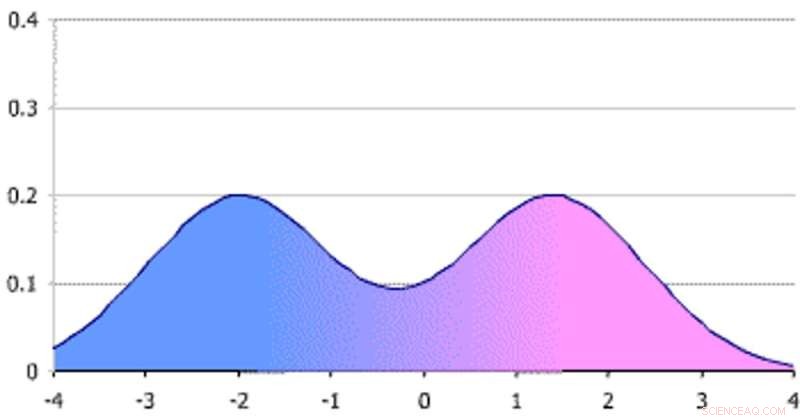

There are a couple of ways paleontologists could test for sexual dimorphism. They could look to see if there are statistically significant differences between fossils from presumed males and females, but there are very few specimens where researchers know the sex. Another method is to see whether there are two distinct groupings of a trait, called a bimodal distribution, which could suggest a difference between males and females.

To tell whether a perceived difference between two groups is true, scientists have traditionally used a tool called the p-value. P-values quantify the probability of a result being due to random chance. If a p-value is low enough, the result is deemed "statistically significant" and considered unlikely to have happened by chance.

But p-values can be heavily influenced by sample size and the design of the study, in addition to the actual degree of sexual dimorphism. Because of the very small sample size of fossils, relying on this statistical technique makes it exceedingly difficult to categorically proclaim what dinosaur species were dimorphic.

The weakness of the black-or-white approach that focuses solely on whether a result is statistically significant has led to hundreds of scientists calling to abandon significance testing with p-values in favor of something called effect size statistics. Using this approach, researchers would simply report the measured difference between two groups and the uncertainty in that measurement.

Very large sex differences can create a bimodal distribution that looks like two distinct groupings of a certain measurement. Credit:Maksim via WikimediaCommons, CC BY

Effect size statistics

I have begun to apply effect size statistics in my research on dinosaurs. My colleagues and I compared sexual dimorphism in body size between three different dinosaurs:the duck-billed Maiasaura, Tyrannosaurus rex and Psittacosaurus, a small relative of Triceratops. None of these species would be expected to show statistically significant size differences between males and females according to p-values. But that approach does not capture the nature of the variation within these species.

When we instead used effect size statistics, we were able to estimate that male and female Maiasaura demonstrate a greater difference in body mass compared to the other two species and that we had a higher confidence in this estimate as well. A few of the characteristics within the data helped reduce the uncertainty. First, we had a large number of Maiasaura fossils, from individuals of various ages. These bones very nicely fit with trajectories of how size changes as an individual grows from juvenile to adult, so we could control for differences due to age and instead focus on differences due to sex.

Additionally, the Maiasaura fossils all come from a single bone bed of individuals that died in the same place at the same time. This means that variation between individuals is likely not due to them being different species from different regions or time periods.

If my colleagues and I had approached the problem expecting a yes or no answer on whether males and females differed in size, we would have completely missed all of these intricacies. Effect size statistics allow researchers to produce much more nuanced and, I think, informative results. It is almost as much a difference in the philosophical approach to science as it is a mathematical one.

Using effect size statistics, researchers were able to determine that the duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura showed a larger amount of dimorphism with the least uncertainty in that estimate compared to other dinosaurs. Credit:Daderot via WikimediaCommons

Studying dinosaur dimorphism is not the only place p-values create issues. Many fields of science, including medicine and psychology, are having similar debates about issues in statistics and a worrying problem of unrepeatable studies.

Embracing uncertainty in data—rather than looking for black-or-white answers to questions like whether male and female dinosaurs were sexually dimorphic—can help elucidate dinosaur biology. But this shift in thinking may be felt far and wide across the sciences. A careful consideration of problems within statistics could have deep impacts across many fields.