Los robots todavía no sostendrán los bolígrafos, pero pueden ayudar a las personas a hacer el trabajo. Crédito:Paul Fleet / Shutterstock.com

Así como los robots han transformado franjas enteras de la economía manufacturera, la inteligencia artificial y la automatización están cambiando el trabajo de la información, dejar que los humanos descarguen el trabajo cognitivo en las computadoras. En periodismo, por ejemplo, Los sistemas de minería de datos alertan a los reporteros sobre posibles noticias, mientras que los newsbots ofrecen nuevas formas para que el público explore la información. Los sistemas de escritura automatizados generan Cobertura deportiva y electoral.

Una pregunta común a medida que estas tecnologías inteligentes se infiltran en varias industrias es cómo se verán afectados el trabajo y la mano de obra. En este caso, quién (o qué) hará periodismo en este mundo automatizado y mejorado por la inteligencia artificial, y como lo van a hacer?

La evidencia que he reunido en mi nuevo libro "Automatizando lo nuevo:cómo los algoritmos están reescribiendo los medios" sugiere que el futuro del periodismo habilitado por la inteligencia artificial todavía tendrá mucha gente alrededor. Sin embargo, los trabajos, Los roles y tareas de esas personas evolucionarán y se verán un poco diferentes. El trabajo humano se hibridará, combinado con algoritmos, para adaptarse a las capacidades de la IA y adaptarse a sus limitaciones.

Aumento, no sustituyendo

Algunas estimaciones sugieren que los niveles actuales de tecnología de inteligencia artificial podrían automatizar solo alrededor del 15% del trabajo de un reportero y el 9% del trabajo de un editor. Los humanos todavía tienen una ventaja sobre la inteligencia artificial que no es de Hollywood en varias áreas clave que son esenciales para el periodismo, incluida la comunicación compleja, pensamiento experto, adaptabilidad y creatividad.

Reportando, escuchando, responder y retroceder, negociar con las fuentes, y luego tener la creatividad para armarlo:la IA no puede realizar ninguna de estas tareas periodísticas indispensables. A menudo puede aumentar el trabajo humano, aunque, para ayudar a las personas a trabajar más rápido o con mejor calidad. Y puede crear nuevas oportunidades para profundizar la cobertura de noticias y hacerla más personalizada para un lector o espectador individual.

El trabajo de la sala de redacción siempre se ha adaptado a las oleadas de nuevas tecnologías, incluida la fotografía, teléfonos, computadoras, o incluso simplemente la fotocopiadora. Los periodistas se adaptarán para trabajar con IA, también. Como tecnología, ya está y seguirá cambiando el trabajo de noticias, a menudo complementa pero rara vez sustituye a un periodista capacitado.

Nuevo trabajo

He descubierto que la mayoría de las veces, Las tecnologías de inteligencia artificial parecen estar creando nuevos tipos de trabajo en el periodismo.

Tomemos, por ejemplo, Associated Press, que en 2017 introdujo el uso de técnicas de inteligencia artificial de visión por computadora para etiquetar las miles de fotos de noticias que maneja todos los días. El sistema puede etiquetar fotos con información sobre qué o quién está en una imagen, su estilo fotográfico, y si una imagen muestra violencia gráfica.

El sistema les da a los editores de fotos más tiempo para pensar en lo que deberían publicar y los libera de pasar mucho tiempo simplemente etiquetando lo que tienen. Pero desarrollarlo requirió mucho trabajo, tanto editorial como técnico:los editores tenían que averiguar qué etiquetar y si los algoritmos estaban a la altura de la tarea, luego, desarrolle nuevos conjuntos de datos de prueba para evaluar el desempeño. Cuando todo eso estuvo hecho, todavía tenían que supervisar el sistema, aprobar manualmente las etiquetas sugeridas para cada imagen para garantizar una alta precisión.

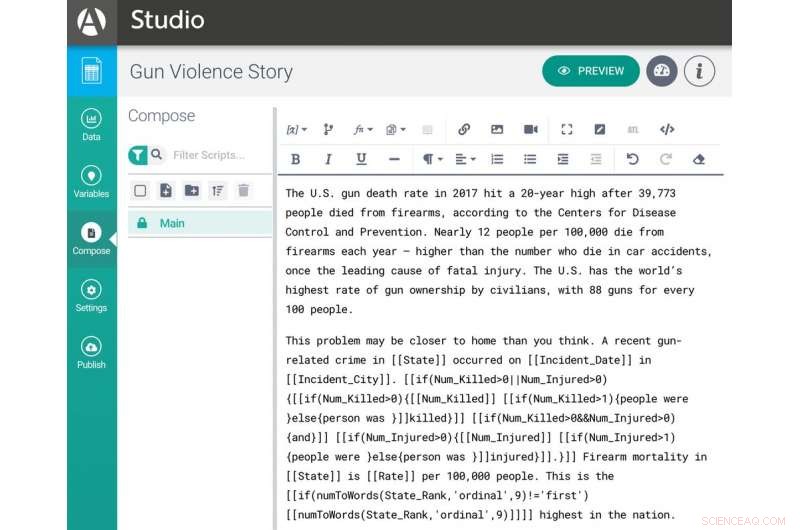

La interfaz de usuario de Arria Studio que muestra la composición de una historia personalizada sobre violencia armada. Crédito:captura de pantalla de Nicholas Diakopoulos de Arria Studio, CC BY-ND

Stuart Myles, el ejecutivo de AP que supervisa el proyecto, me dijo que se necesitaron alrededor de 36 meses-persona de trabajo, repartidos en un par de años y más de una docena de editoriales, personal técnico y administrativo. Aproximadamente un tercio del trabajo, me dijo, involved journalistic expertise and judgment that is especially hard to automate. While some of the human supervision may be reduced in the future, he thinks that people will still need to do ongoing editorial work as the system evolves and expands.

Semi-automated content production

En el Reino Unido, the RADAR project semi-automatically pumps out around 8, 000 localized news articles per month. The system relies on a stable of six journalists who find government data sets tabulated by geographic area, identify interesting and newsworthy angles, and then develop those ideas into data-driven templates. The templates encode how to automatically tailor bits of the text to the geographic locations identified in the data. Por ejemplo, a story could talk about aging populations across Britain, and show readers in Luton how their community is changing, with different localized statistics for Bristol. The stories then go out by wire service to local media who choose which to publish.

The approach marries journalists and automation into an effective and productive process. The journalists use their expertise and communication skills to lay out options for storylines the data might follow. They also talk to sources to gather national context, and write the template. The automation then acts as a production assistant, adapting the text for different locations.

RADAR journalists use a tool called Arria Studio, which offers a glimpse of what writing automated content looks like in practice. It's really just a more complex interface for word processing. The author writes fragments of text controlled by data-driven if-then-else rules. Por ejemplo, in an earthquake report you might want a different adjective to talk about a quake that is magnitude 8 than one that is magnitude 3. So you'd have a rule like, IF magnitude> 7 THEN text ="strong earthquake, " ELSE IF magnitude <4 THEN text ="minor earthquake." Tools like Arria also contain linguistic functionality to automatically conjugate verbs or decline nouns, making it easier to work with bits of text that need to change based on data.

Authoring interfaces like Arria allow people to do what they're good at:logically structuring compelling storylines and crafting creative, nonrepetitive text. But they also require some new ways of thinking about writing. Por ejemplo, template writers need to approach a story with an understanding of what the available data could say—to imagine how the data could give rise to different angles and stories, and delineate the logic to drive those variations.

Supervision, management or what journalists might call "editing" of automated content systems are also increasingly occupying people in the newsroom. Maintaining quality and accuracy is of the utmost concern in journalism.

RADAR has developed a three-stage quality assurance process. Primero, a journalist will read a sample of all of the articles produced. Then another journalist traces claims in the story back to their original data source. As a third check, an editor will go through the logic of the template to try to spot any errors or omissions. It's almost like the work a team of software engineers might do in debugging a script—and it's all work humans must do, to ensure the automation is doing its job accurately.

Developing human resources

Initiatives like those at the Associated Press and at RADAR demonstrate that AI and automation are far from destroying jobs in journalism. They're creating new work—as well as changing existing jobs. The journalists of tomorrow will need to be trained to design, update, tweak, validate, correct, supervise and generally maintain these systems. Many may need skills for working with data and formal logical thinking to act on that data. Fluency with the basics of computer programming wouldn't hurt either.

As these new jobs evolve, it will be important to ensure they're good jobs—that people don't just become cogs in a much larger machine process. Managers and designers of this new hybrid labor will need to consider the human concerns of autonomy, effectiveness and usability. But I'm optimistic that focusing on the human experience in these systems will allow journalists to flourish, and society to reap the rewards of speed, breadth of coverage and increased quality that AI and automation can offer.

Este artículo se vuelve a publicar de The Conversation bajo una licencia Creative Commons. Lea el artículo original.