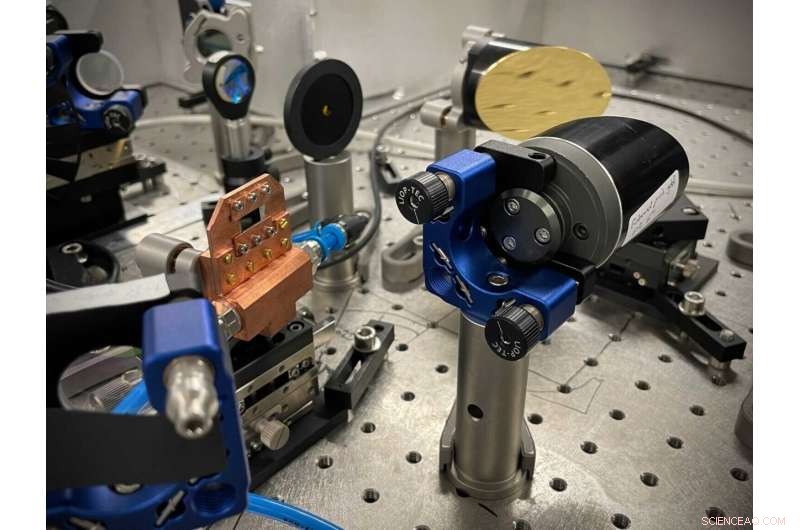

Las nanoláminas semiconductoras en la montura de cobre refrigerada por agua convierten un pulso de láser infrarrojo en un pulso de terahercios efectivamente unipolar. El equipo dice que su emisor de terahercios podría hacerse para caber dentro de una caja de fósforos. Crédito:Christian Meineke, Huber Lab, Universidad de Ratisbona

Un pulso láser que eluda la simetría inherente de las ondas de luz podría manipular la información cuántica, acercándonos potencialmente a la computación cuántica a temperatura ambiente.

El estudio, dirigido por investigadores de la Universidad de Ratisbona y la Universidad de Michigan, también podría acelerar la computación convencional.

La computación cuántica tiene el potencial de acelerar las soluciones a problemas que necesitan explorar muchas variables al mismo tiempo, incluido el descubrimiento de fármacos, la predicción meteorológica y el cifrado para la ciberseguridad. Los bits de computadora convencionales codifican un 1 o un 0, pero los bits cuánticos, o qubits, pueden codificar ambos al mismo tiempo. Básicamente, esto permite que las computadoras cuánticas trabajen en múltiples escenarios simultáneamente, en lugar de explorarlos uno tras otro. Sin embargo, estos estados mixtos no duran mucho, por lo que el procesamiento de la información debe ser más rápido de lo que pueden reunir los circuitos electrónicos.

Si bien los pulsos láser se pueden usar para manipular los estados de energía de los qubits, son posibles diferentes formas de computación si los portadores de carga utilizados para codificar información cuántica se pueden mover, incluido un enfoque a temperatura ambiente. La luz de terahercios, que se encuentra entre la radiación infrarroja y la de microondas, oscila lo suficientemente rápido como para proporcionar la velocidad, pero la forma de la onda también es un problema. Es decir, las ondas electromagnéticas están obligadas a producir oscilaciones tanto positivas como negativas, que suman cero.

El ciclo positivo puede mover portadores de carga, como los electrones. Pero luego el ciclo negativo hace que las cargas regresen a donde comenzaron. Para controlar de manera confiable la información cuántica, se necesita una onda de luz asimétrica.

"Lo óptimo sería una 'onda' unipolar completamente direccional, por lo que solo habría un pico central, sin oscilaciones. Ese sería el sueño. Pero la realidad es que los campos de luz que se propagan tienen que oscilar, así que tratamos de hacer the oscillations as small as we can," said Mackillo Kira, U-M professor of electrical engineering and computer science and leader of the theory aspects of the study in Light:Science &Applications .

Since waves that are only positive or only negative are physically impossible, the international team came up with a way to do the next best thing. They created an effectively unipolar wave with a very sharp, high-amplitude positive peak flanked by two long, low-amplitude negative peaks. This makes the positive peak forceful enough to move charge carriers while the negative peaks are too small to have much effect.

They did this by carefully engineering nanosheets of a gallium arsenide semiconductor to design the terahertz emission through the motion of electrons and holes, which are essentially the spaces left behind when electrons move in semiconductors. The nanosheets, each about as thick as one thousandth of a hair, were made in the lab of Dominique Bougeard, a professor of physics at the University of Regensburg in Germany.

Then, the group of Rupert Huber, also a professor of physics at the University of Regensburg, stacked the semiconductor nanosheets in front of a laser. When the near-infrared pulse hit the nanosheet, it generated electrons. Due to the design of the nanosheets, the electrons welcomed separation from the holes, so they shot forward. Then, the pull from the holes drew the electrons back. As the electrons rejoined the holes, they released the energy they'd picked up from the laser pulse as a strong positive terahertz half-cycle preceded and followed by a weak, long negative half-cycle.

"The resulting terahertz emission is stunningly unipolar, with the single positive half-cycle peaking about four times higher than the two negative ones," Huber said. "We have been working for many years on light pulses with fewer and fewer oscillation cycles. The possibility of generating terahertz pulses so short that they effectively comprise less than a single half-oscillation cycle was beyond our bold dreams."

Next, the team intends to use these pulses to manipulate electrons in room temperature quantum materials, exploring mechanisms for quantum information processing. The pulses could also be used for ultrafast processing of conventional information.

"Now that we know the key factor of unipolar pulses, we may be able to shape terahertz pulses to be even more asymmetric and tailored for controlling semiconductor qubits," said Qiannan Wen, a Ph.D. student in applied physics at U-M and a co-first-author of the study, along with Christian Meineke and Michael Prager, Ph.D. students in physics at the University of Regensburg. Light could make semiconductor computers a million times faster or even go quantum