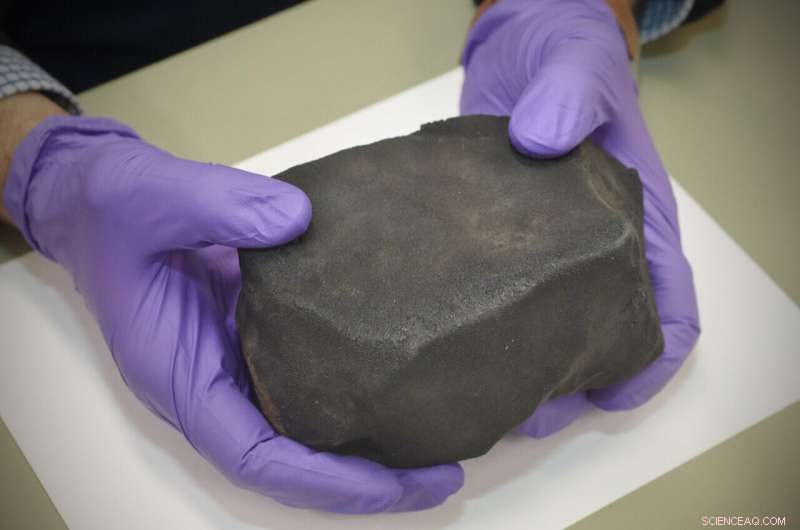

La masa principal del meteorito de Aguas Zarcas en el Museo Field. Crédito:John Weinstein, Museo Field

En 2019, la nave espacial OSIRIS-REx de la NASA envió imágenes de un fenómeno geológico que nadie había visto antes:los guijarros salían volando de la superficie del asteroide Bennu. El asteroide parecía estar disparando enjambres de rocas del tamaño de canicas. Los científicos nunca antes habían visto este comportamiento de un asteroide, y es un misterio exactamente por qué sucede. Pero en un nuevo artículo en Nature Astronomy , los investigadores muestran la primera evidencia de este proceso en un meteorito.

"Es fascinante ver algo que acaba de descubrir una misión espacial en un asteroide a millones de kilómetros de la Tierra, y encontrar un registro del mismo proceso geológico en la colección de meteoritos del museo", dice Philipp Heck, curador de Robert A. Pritzker. de Meteoritics en el Field Museum de Chicago y autor principal de Nature Astronomy estudiar.

Los meteoritos son trozos de roca que caen a la Tierra desde el espacio exterior; pueden estar hechos de pedazos de lunas y planetas, pero la mayoría de las veces son pedazos desprendidos de asteroides. El meteorito de Aguas Zarcas lleva el nombre de la localidad costarricense donde cayó en 2019; llegó al Field Museum como una donación de Terry y Gail Boudreaux. Heck y su estudiante, Xin Yang, estaban preparando el meteorito para otro estudio cuando notaron algo extraño.

"Estábamos tratando de aislar minerales muy pequeños del meteorito congelándolos con nitrógeno líquido y descongelándolos con agua tibia para romperlos", dice Yang, estudiante de posgrado en el Field Museum y la Universidad de Chicago y el primer artículo del artículo. autor. "Eso funciona para la mayoría de los meteoritos, pero este fue un poco extraño:encontramos algunos fragmentos compactos que no se romperían".

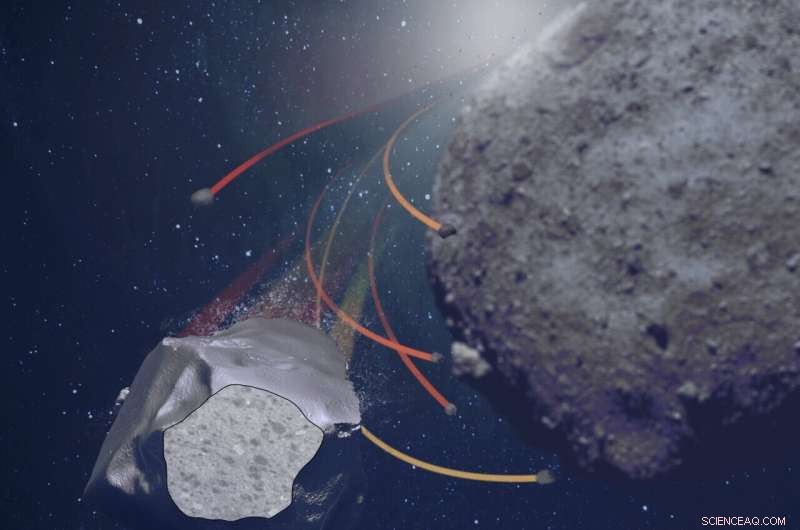

Representación artística del proceso de mezcla de guijarros del cuerpo matriz de Aguas Zarcas. Fragmentos del tamaño de un guijarro son expulsados y redepositados en la superficie del asteroide. Crédito:Abril I. Neander. Imagen del asteroide:NASA/Goddard/Universidad de Arizona.

Heck dice que encontrar fragmentos de meteoritos que no se desintegren no es insólito, pero los científicos generalmente simplemente se encogen de hombros y sacan el mortero. "Xin tenía una mente muy abierta, dijo:'No voy a convertir estos guijarros en arena, esto es interesante'", dice Heck. En cambio, los investigadores idearon un plan para descubrir qué eran estos guijarros y por qué eran tan resistentes a romperse.

"Hicimos tomografías computarizadas para ver cómo se comparan los guijarros con las otras rocas que componen el meteorito", dice Heck. "What was striking is that these components were all squished— normally, they'd be spherical— and they all had the same orientation. They were all deformed in the same direction, by one process." Something had happened to the pebbles that didn't happen to the rest of the rock around them.

Pebbles ejected off the surface of asteroid Bennu were observed frequently by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. This observation inspired this study. Credit:NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona/Lockheed Martin.

"This was exciting, we were very curious about what it meant," says Yang.

The scientists had a clue, though, from the 2019 OSIRIS-REx findings. From there, they put together a hypothesis, which they supported with physical models. The asteroid underwent a high-speed collision, and the area of impact got deformed. That deformed rock eventually broke apart due to the huge temperature differences the asteroid experiences when it rotates, since the side facing the sun is more than 300° F warmer than the side facing away. "This constant thermal cycling makes the rock brittle, and it breaks apart into gravel," says Heck.

These pebbles are then ejected from the asteroid's surface. "We don't yet know what the process is that ejects the pebbles," says Heck— they might be dislodged by smaller impacts other space collisions, or they might just get released by the thermal stress the asteroid undergoes. But once the pebbles are disturbed, Heck says, "you don't need much to eject something— the escape velocity is very low." A recent study of Bennu revealed that its surface is loosely bound and behaves like popcorn in a bucket.

Sampling of the Aguas Zarcas meteorite at the Field Museum of Natural History. Credit:Drew Carhart, Field Museum

The pebbles then entered a very slow orbit around the asteroid, and eventually, they fell back down to its surface further away where there was no deformation. Then, Heck and Yang say, the asteroid underwent another collision, the loose mixed pebbles on the surface got transformed into a solid rock. "It basically packed everything together, and this loose gravel became a cohesive rock," says Heck. The same impact may have dislodged the new rock, sending it careening into space. Eventually, that chunk fell to Earth as the Aguas Zarcas meteorite, carrying evidence of the pebble mixing.

This could explain the pebbles present in Aguas Zarcas, making the meteorite the first physical evidence of the geological process observed by OSIRIS-REx on Bennu. "It provides a new way of explaining the way that minerals on the surfaces of asteroids get mixed," says Yang.

That's a big deal, Heck says, because for a long time, scientists assumed that the main way that the minerals on the surfaces of asteroids get rearranged is through big crashes, which don't happen very often. "From OSIRIS-REx we know that these particle ejection events are much more frequent than these high-velocity impacts," says Heck, "so they probably play a more important role in determining the makeup of asteroids and meteorites."

Aguas Zarcas is the first meteorite to show signs of this behavior, but it's probably not the only one. "We would expect this in other meteorites," says Heck. "People just haven't looked for it yet." 'Fireball' meteorite contains pristine extraterrestrial organic compounds