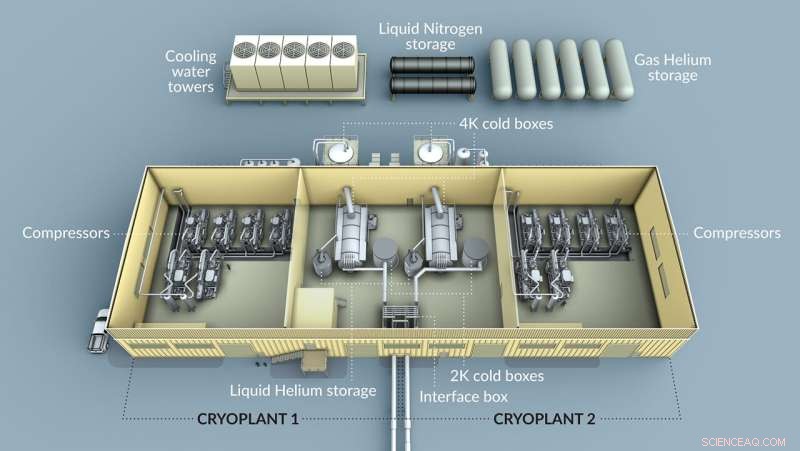

Un esquema de la crioplanta LCLS-II. Crédito:Greg Stewart/Laboratorio Nacional de Aceleradores de SLAC

Hoy en día, solo toma una hora y media hacer que un acelerador de partículas superconductoras en el Laboratorio Nacional de Aceleradores SLAC del Departamento de Energía sea más frío que el espacio exterior.

"Ahora hace clic en un botón y la máquina pasa de 4,5 Kelvin a 2 Kelvin", dijo Eric Fauve, director del equipo criogénico de SLAC.

Si bien el proceso ahora está completamente automatizado, llevar este acelerador, llamado LCLS-II, a 2 Kelvin, o menos 456 grados Fahrenheit, tomó seis años de diseño, construcción, instalación y puesta en marcha de un sistema complejo.

El LCLS original, o Linac Coherent Light Source, acelera los electrones para finalmente producir rayos X que se utilizan en experimentos de sondeo de átomos y moléculas. LCLS-II funcionará simultáneamente con LCLS. Sin embargo, a diferencia de LCLS, que utiliza piezas de cobre a temperatura ambiente para acelerar los electrones, la actualización de LCLS-II emplea criomódulos superconductores. Estos criomódulos imparten electrones con energía de manera más eficiente, lo que ayudará a generar pulsos de rayos X más potentes para ampliar las posibilidades experimentales en todos los campos.

Pero, mientras que LCLS puede operar a temperatura ambiente, LCLS-II debe enfriarse a 2 Kelvin, solo 4 grados Fahrenheit por encima del cero absoluto, para volverse superconductor.

Y eso significaba que SLAC necesitaba un equipo que se concentrara en cosas frías.

Montando un equipo para montar una crioplanta

Antes de que se enfriara el LCLS-II, no había ningún grupo dedicado a la criogenia en SLAC.

"Nuestro mayor desafío fue que esta era la primera vez que hacíamos esto con un nuevo equipo", dijo Fauve.

El equipo criogénico de LCLS-II, que ahora consta de 20 operadores e ingenieros, se formó en 2016 en SLAC para construir la instalación que enfría el acelerador:una planta criogénica.

"Este es un sistema complicado con muchos subsistemas que funcionan en conjunto", dijo Viswanath Ravindranath, ingeniero principal de procesos criogénicos de LCLS-II.

SLAC trabajó en estrecha colaboración con ingenieros del Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory y Jefferson National Accelerator Facility del DOE, así como con empresas criogénicas líderes para diseñar y adquirir materiales para la crioplanta.

"Esta colaboración permitió que el proyecto LCLS-II se beneficiara de los mejores recursos criogénicos dentro de los laboratorios del DOE y en otros lugares", dijo Fauve.

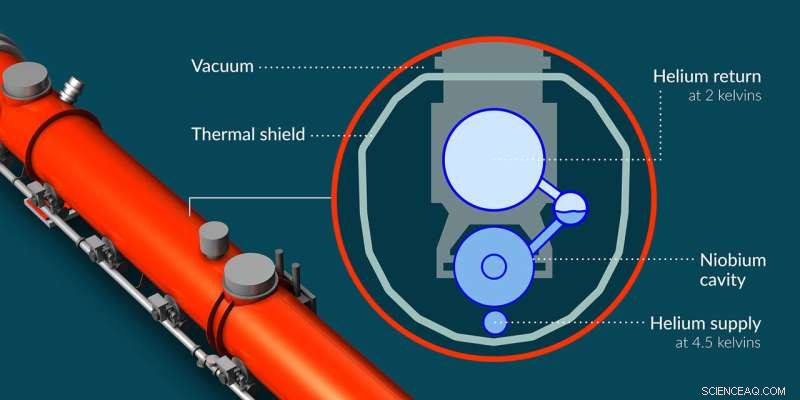

Una sección transversal del acelerador LCLS-II que muestra por dónde entra y sale el helio líquido y gaseoso del sistema. Crédito:Greg Stewart/Laboratorio Nacional de Aceleradores de SLAC

La crioplanta se llena con helio, que se enfría y luego se bombea a LCLS-II. Mientras que todos los demás elementos se congelan por debajo de 4 Kelvin, el helio puede permanecer fluido, y a 2 Kelvin, el helio se vuelve superfluido, lo que significa que fluye sin viscosidad. Ese hecho, y la capacidad del helio superfluido para conducir el calor mejor que cualquier otra sustancia conocida, lo convierten en el refrigerante perfecto para enfriar un acelerador superconductor.

Antes de que comience el enfriamiento, los remolques llenos de tanques con forma de perrito caliente entregan helio gaseoso a temperatura ambiente (alrededor de 300 Kelvin) a los tanques de almacenamiento al aire libre de la crioplanta. La crioplanta requiere un total de cuatro toneladas métricas de helio.

Pero este helio llega impuro. Eventualmente, cualquier impureza se congelará y obstruirá el sistema, por lo que los primeros purificadores deben atrapar la humedad o los gases no deseados, como el nitrógeno, para lograr un 99,999 % de helio.

Después de la purificación, los compresores elevan la presión del helio. La presión y la temperatura de un gas están acopladas:a medida que disminuye la presión, también disminuye la temperatura. So, while helpful later, this incidentally raises helium's temperature to 370 Kelvin.

Following compression, five large towers containing cooling water are used to lower helium's temperature back down to 300 Kelvin. The gas then enters the cryoplant's 4K cold box, which is a giant, uber-complicated helium refrigerator.

In the cold box, liquid nitrogen running 77 Kelvin knocks the helium down from 300 Kelvin to 80 Kelvin in a heat exchanger. In this device, the warm helium gas and colder liquid nitrogen travel in opposite directions while separated by a thin metal plate, transferring heat through the plate from the helium to the nitrogen. The plant uses 20 metric tons of liquid nitrogen every other day.

The helium then runs through a set of four turboexpanders. Now the initial gas-compressing step pays off:the turboexpanders expand the high-pressure gas, lowering its pressure enough to bring the helium all the way to 5.5 Kelvin.

However, the helium has more expanding to do before it can leave the cold box. It travels through a valve that has lower pressure on the other side. This lower pressure causes the gas to expand, lowering its pressure and bringing its temperature down to 4.5 Kelvin (hence the name of the 4K cold box), where it becomes a liquid.

This liquid helium is then sent through pipes to the accelerator's cryomodules, where it cools the machine to 4.5 Kelvin.

Once the 4K cold box was up and running, it took the Cryogenic team one week to cool LCLS-II from room temperature to 4.5 Kelvin, which it reached for the first time on March 28, 2022. But that's not cold enough!

Colder still

To reach 2 Kelvin, the 4.5 Kelvin helium undergoes yet another (final) expansion through a valve in the accelerator's cryomodules. Again, the lower pressure on the other side of the valve causes helium's pressure to drop. This cools helium to the goal temperature of 2 Kelvin.

Creating the low pressure inside the cryomodule is a feat in itself.

"The magic happens when it goes through that valve, but only because we have a train of cold compressors that maintains the pressure in the cryomodule at very low pressure," Fauve said. This set of five compressors stationed after the valve create the pivotal pressure difference on either side of the valve.

After months of turning on and configuring this cooling system, LCLS-II finally reached 2 Kelvin on April 15.

"Everything was possible because of all the hard work over the years from so many smart and dedicated people," said Swapnil Shrishrimal, cryogenic process and controls engineer for LCLS-II. "Being a small team, as well as a young team, we are very proud of the system we commissioned."

When the electron beam is on and being accelerated by the cryomodules, the 2 Kelvin helium will absorb heat from the accelerator, boil, and turn back into gas. That gas is injected back into the 4K cold box to help cool warmer helium.

"We don't want to waste the cooling capacity, so we try to recover as much of it as possible," Ravindranath said. The system recycles the helium, which is expensive, although essential for long-term operation.

The Cryogenic team actually built two cryoplants, which share a building, but LCLS-II only uses one. The second cryoplant will support planned upgrades to LCLS-II. When both cryoplants are on they will use approximately 10 megawatts of electrical power.

Only four other cryoplants in the United States cool this much helium to 2 Kelvin. Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, which both house cryoplants of similar magnitude, supported SLAC's design and procurement of equipment. SLAC collaborated with Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and CERN as well.

"The years of expertise and support of our partner labs allowed us to do this," Shrishrimal said. Fauve also credits the team's success to their extensive planning and dedication. The entire Cryogenic team stayed on site during the pandemic to continue bringing the plant to life.

"Even when SLAC was shut down, if you were at the cryoplant you would not be able to tell the difference before and during COVID," Fauve said, except for the masks and social distancing, of course.

LCLS-II is expected to produce its first X-rays early next year. The Cryogenic team feels confident they will continue to run their very complicated refrigerator with ease.

"It's a pretty nice and easy operation now because everything is automated," Shrishrimal said. Superconducting X-ray laser reaches operating temperature colder than outer space