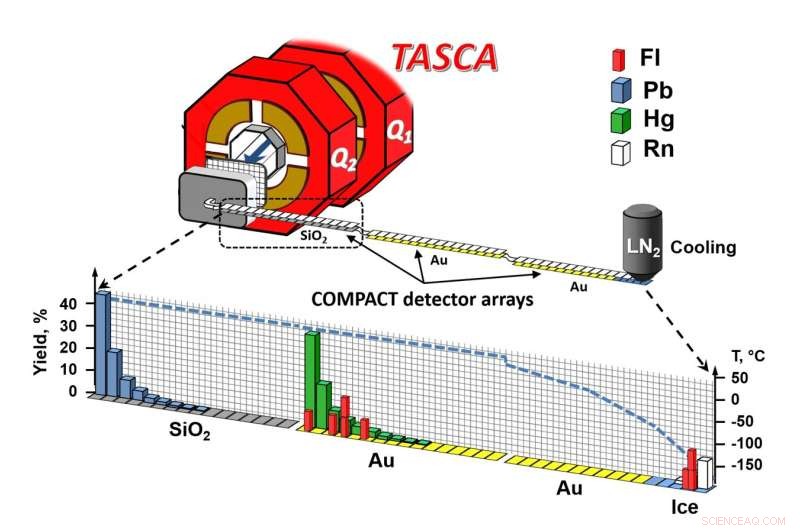

Vista esquemática de la configuración del experimento. Crédito:A. Yakushev, GSI/FAIR

Un equipo de investigación internacional obtuvo nuevos conocimientos sobre las propiedades químicas del elemento superpesado flerovium, elemento 114, en las instalaciones del acelerador de GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung en Darmstadt. Las mediciones muestran que el flerovio es el metal más volátil de la tabla periódica. Flerovium es, por lo tanto, el elemento más pesado de la tabla periódica que se ha estudiado químicamente.

Con los resultados, publicados en la revista Frontiers in Chemistry , GSI contribuye al estudio de la química de los elementos superpesados y abre nuevas perspectivas para la instalación internacional FAIR (Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research), que se encuentra actualmente en construcción.

Bajo el liderazgo de grupos de Darmstadt y Mainz, los dos isótopos de flerovium de vida más larga que se conocen actualmente, flerovium-288 y flerovium-289, se produjeron utilizando las instalaciones del acelerador en GSI/FAIR y se investigaron químicamente en la configuración experimental de TASCA. En la tabla periódica, el flerovio se coloca debajo del plomo, un metal pesado.

Sin embargo, las primeras predicciones habían postulado que los efectos relativistas de la alta carga en el núcleo del elemento superpesado sobre sus electrones de valencia conducirían a un comportamiento similar al de un gas noble, mientras que las más recientes habían sugerido un comportamiento débilmente metálico. Dos experimentos químicos realizados anteriormente, uno de ellos en GSI en Darmstadt en 2009, dieron lugar a interpretaciones contradictorias.

Mientras que los tres átomos observados en el primer experimento se usaron para inferir un comportamiento similar al de un gas noble, los datos obtenidos en GSI indicaron un carácter metálico basado en dos átomos. Los dos experimentos no pudieron establecer claramente el carácter. Los nuevos resultados muestran que, como se esperaba, el flerovium es inerte pero capaz de formar enlaces químicos más fuertes que los gases nobles, si las condiciones son adecuadas. Por lo tanto, el flerovio es el metal más volátil de la tabla periódica.

Flerovium es, por lo tanto, el elemento químico más pesado cuyo carácter se ha estudiado experimentalmente. Con la determinación de las propiedades químicas, GSI/FAIR confirman su posición de liderazgo en la investigación de elementos superpesados.

"Explorar los límites de la tabla periódica ha sido un pilar del programa de investigación de GSI desde el principio y lo será en FAIR en el futuro. El hecho de que unos pocos átomos ya se puedan usar para explorar las primeras propiedades químicas fundamentales, dando una indicación de cómo se comportarían cantidades más grandes de estas sustancias es fascinante y posible gracias a la poderosa instalación del acelerador y la experiencia de la colaboración mundial", dice el profesor Paolo Giubellino, Director General Científico de GSI y FAIR. "Con FAIR, llevamos el universo al laboratorio y exploramos los límites de la materia, también de los elementos químicos".

Seis semanas de experimentación

Los experimentos realizados en GSI/FAIR para aclarar la naturaleza química del flerovium duraron un total de seis semanas. For this purpose, four trillion calcium-48 ions were accelerated to ten percent of the speed of light every second by the GSI linear accelerator UNILAC and fired at a target containing plutonium-244, resulting in the formation of a few flerovium atoms per day.

The formed flerovium atoms recoiled from the target into the gas-filled separator TASCA. In its magnetic field, the formed isotopes, flerovium-288 and flerovium-289, which have lifetimes on the order of a second, were separated from the intense calcium ion beam and from byproducts of the nuclear reaction. They penetrated a thin film, thus entering the chemistry apparatus, where they were stopped in a helium/argon gas mixture.

This gas mixture flushed the atoms into the COMPACT gas chromatography apparatus, where they first came into contact with silicon oxide surfaces. If the bond to silicon oxide was too weak, the atoms were transported further, over gold surfaces—first those kept at room temperature, and then over increasingly colder ones, down to about –160 °C.

The surfaces were deposited as a thin coating on special nuclear radiation detectors, which registered individual atoms by spatially resolved detection of the radioactive decay. Since the decay products undergo further radioactive decay after a short lifetime, each atom leaves a characteristic signature of several events from which the presence of a flerovium atom can unambiguously be inferred.

One atom per week for chemistry

"Thanks to the combination of the TASCA separator, the chemical separation and the detection of the radioactive decays, as well as the technical development of the gas chromatography apparatus since the first experiment, we have succeeded in increasing the efficiency and reducing the time required for the chemical separation to such an extent that we were able to observe one flerovium atom every week," explains Dr. Alexander Yakushev of GSI/FAIR, the spokesperson for the international experiment collaboration.

Six such decay chains were found in the data analysis. Since the setup is similar to that of the first GSI experiment, the newly obtained data could be combined with the two atoms observed at that time and analyzed together.

None of the decay chains appeared within the range of the silicon oxide-coated detector, indicating that flerovium does not form a substantial bond with silicon oxide. Instead, all were transported with the gas into the gold-coated portion of the apparatus within less than a tenth of a second.

The eight events formed two zones:a first in the region of the gold surface at room temperature, and a second in the later part of the chromatograph, at temperatures so low that a very thin layer of ice covered the gold, so that adsorption occurred on ice.

From experiments with lead, mercury and radon atoms, which served as representatives of heavy metals, weakly reactive metals as well as noble gases, it was known that lead forms a strong bond with silicon oxide, while mercury reaches the gold detector. Radon even flies over the first part of the gold detector at room temperature and is only partially retained at the lowest temperatures. Flerovium results could be compared with this behavior.

Apparently, two types of interaction of a flerovium species with the gold surface were observed. The deposition on gold at room temperature indicates the formation of a relatively strong chemical bond, which does not occur in noble gases. On the other hand, some of the atoms appear never to have had the opportunity to form such bonds and have been transported over long distances of the gold surface, down to the lowest temperatures.

This detector range represents a trap for all elemental species. This complicated behavior can be explained by the morphology of the gold surface:it consists of small gold clusters, at the boundaries of which very reactive sites occur, apparently allowing the flerovium to bond. The fact that some of the flerovium atoms were able to reach the cold region indicates that only the atoms that encountered such sites formed a bond, unlike mercury, which was retained on gold in any case.

Thus, the chemical reactivity of flerovium is weaker than that of the volatile metal mercury. The current data cannot completely rule out the possibility that the first deposition zone on gold at room temperature is due to the formation of flerovium molecules. It also follows from this hypothesis, though, that flerovium is chemically more reactive than a noble gas element.

The exotic plutonium target material for the production of the flerovium was provided in part by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), U.S.. In the Department of Chemistry's TRIGA site at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), the material was electrolytically deposited onto thin titanium foils fabricated at GSI/FAIR.

"There is not much of this material available in the world, and we are fortunate to have been able to use it for these experiments that would not otherwise be possible," said Dr. Dawn Shaughnessy, head of the Nuclear and Chemical Sciences Division at LLNL. "This international collaboration brings together skills and expertise from around the world to solve difficult scientific problems and answer long-standing questions, such as the chemical properties of flerovium."

"Our accelerator experiment was complemented by a detailed study of the detector surface in collaboration with several GSI departments as well as the Department of Chemistry and the Institute of Physics at JGU. This has proven to be key to understanding the chemical character of flerovium. As a result, the data from the two earlier experiments are now understandable and compatible with our new conclusions," says Christoph Düllmann, professor of nuclear chemistry at JGU and head of the research groups at GSI and at the Helmholtz Institute Mainz (HIM), a collaboration between GSI and JGU.

How the relativistic effects affect its neighbors, the elements nihonium (element 113) and moscovium (element 115), which have also only been officially recognized in recent years, is the subject of subsequent experiments. Initial data have already been obtained as part of the FAIR Phase 0 program at GSI. Furthermore, the researchers expect that significantly more stable isotopes of flerovium exist, but these have not yet been found. However, the researchers now already know that they can expect to find a metallic element. Nuclear physicist's voyage toward a mythical island