Crédito:Unsplash/CC0 Dominio público

Las personas que viven con diabetes tipo 1 deben seguir cuidadosamente los regímenes de insulina prescritos todos los días, recibiendo inyecciones de la hormona mediante jeringa, bomba de insulina o algún otro dispositivo. Y sin tratamientos viables a largo plazo, este curso de tratamiento es una sentencia de por vida.

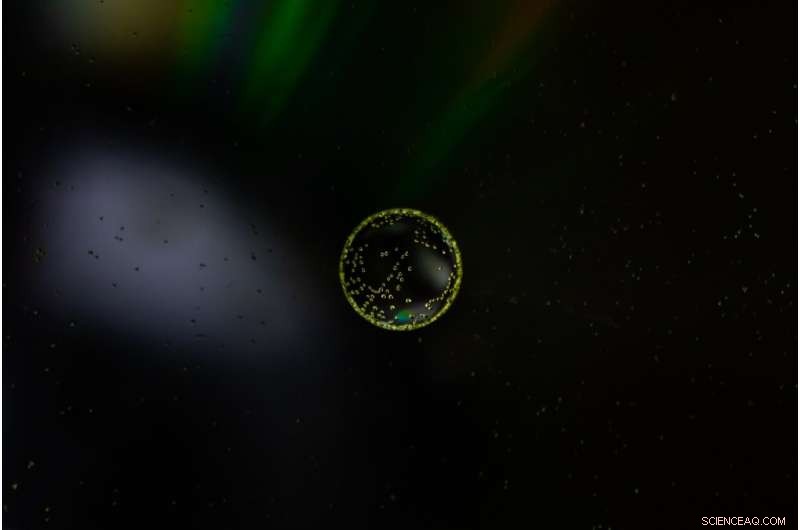

Los islotes pancreáticos controlan la producción de insulina cuando cambian los niveles de azúcar en la sangre y, en la diabetes tipo 1, el sistema inmunitario del cuerpo ataca y destruye las células productoras de insulina. El trasplante de islotes ha surgido en las últimas décadas como una posible cura para la diabetes tipo 1. Con islotes sanos trasplantados, es posible que los pacientes con diabetes tipo 1 ya no necesiten inyecciones de insulina, pero los esfuerzos de trasplante han enfrentado contratiempos a medida que el sistema inmunitario continúa rechazando eventualmente nuevos islotes. Los fármacos inmunosupresores actuales ofrecen una protección inadecuada para las células y los tejidos trasplantados y están plagados de efectos secundarios indeseables.

Ahora, un equipo de investigadores de la Universidad Northwestern ha descubierto una técnica para ayudar a que la inmunomodulación sea más eficaz. El método utiliza nanoportadores para rediseñar la rapamicina inmunosupresora de uso común. Utilizando estos nanoportadores cargados de rapamicina, los investigadores generaron una nueva forma de inmunosupresión capaz de dirigirse a células específicas relacionadas con el trasplante sin suprimir respuestas inmunitarias más amplias.

El artículo se publicó hoy en la revista Nature Nanotechnology . El equipo de Northwestern está dirigido por Evan Scott, profesor Kay Davis y profesor asociado de ingeniería biomédica en la Escuela de Ingeniería McCormick de Northwestern y microbiología-inmunología en la Facultad de Medicina Feinberg de la Universidad de Northwestern, y Guillermo Ameer, profesor de Ingeniería Biomédica Daniel Hale Williams. en McCormick y Cirugía en Feinberg. Ameer también se desempeña como director del Centro de Ingeniería Regenerativa Avanzada (CARE).

Especificando el ataque del cuerpo

Ameer ha estado trabajando para mejorar los resultados del trasplante de islotes al proporcionar a los islotes un entorno diseñado, utilizando biomateriales para optimizar su supervivencia y función. Sin embargo, los problemas asociados con la inmunosupresión sistémica tradicional siguen siendo una barrera para el manejo clínico de los pacientes y también deben abordarse para tener un verdadero impacto en su atención, dijo Ameer.

"Esta fue una oportunidad para asociarnos con Evan Scott, un líder en inmunoingeniería, y participar en una colaboración de investigación de convergencia que fue bien ejecutada con gran atención a los detalles por parte de Jacqueline Burke, becaria de investigación de posgrado de la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias", dijo Ameer.

La rapamicina está bien estudiada y se usa comúnmente para suprimir las respuestas inmunitarias durante otros tipos de tratamientos y trasplantes, destaca por su amplia gama de efectos en muchos tipos de células en todo el cuerpo. Normalmente administrada por vía oral, la dosis de rapamicina debe controlarse cuidadosamente para evitar efectos tóxicos. Sin embargo, en dosis más bajas tiene poca eficacia en casos como el trasplante de islotes.

Scott, también miembro de CARE, dijo que quería ver cómo se podía mejorar el fármaco colocándolo en una nanopartícula y "controlando a dónde va dentro del cuerpo".

"Para evitar los amplios efectos de la rapamicina durante el tratamiento, el fármaco normalmente se administra en dosis bajas ya través de vías específicas de administración, principalmente por vía oral", dijo Scott. "Pero en el caso de un trasplante, debe administrar suficiente rapamicina para suprimir sistémicamente las células T, lo que puede tener efectos secundarios significativos como pérdida de cabello, llagas en la boca y un sistema inmunitario debilitado en general".

Following a transplant, immune cells, called T cells, will reject newly introduced foreign cells and tissues. Immunosuppressants are used to inhibit this effect but can also impact the body's ability to fight other infections by shutting down T cells across the body. But the team formulated the nanocarrier and drug mixture to have a more specific effect. Instead of directly modulating T cells—the most common therapeutic target of rapamycin—the nanoparticle would be designed to target and modify antigen presenting cells (APCs) that allow for more targeted, controlled immunosuppression.

Using nanoparticles also enabled the team to deliver rapamycin through a subcutaneous injection, which they discovered uses a different metabolic pathway to avoid extensive drug loss that occurs in the liver following oral administration. This route of administration requires significantly less rapamycin to be effective—about half the standard dose.

"We wondered, can rapamycin be re-engineered to avoid non-specific suppression of T cells and instead stimulate a tolerogenic pathway by delivering the drug to different types of immune cells?" Scott said. "By changing the cell types that are targeted, we actually changed the way that immunosuppression was achieved."

A 'pipe dream' come true in diabetes research

The team tested the hypothesis on mice, introducing diabetes to the population before treating them with a combination of islet transplantation and rapamycin, delivered via the standard Rapamune oral regimen and their nanocarrier formulation. Beginning the day before transplantation, mice were given injections of the altered drug and continued injections every three days for two weeks.

The team observed minimal side effects in the mice and found the diabetes was eradicated for the length of their 100-day trial; but the treatment should last the transplant's lifespan. The team also demonstrated the population of mice treated with the nano-delivered drug had a "robust immune response" compared to mice given standard treatments of the drug.

The concept of enhancing and controlling side effects of drugs via nanodelivery is not a new one, Scott said. "But here we're not enhancing an effect, we are changing it—by repurposing the biochemical pathway of a drug, in this case mTOR inhibition by rapamycin, we are generating a totally different cellular response."

The team's discovery could have far-reaching implications. "This approach can be applied to other transplanted tissues and organs, opening up new research areas and options for patients," Ameer said. "We are now working on taking these very exciting results one step closer to clinical use."

Jacqueline Burke, the first author on the study and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow and researcher working with Scott and Ameer at CARE, said she could hardly believe her readings when she saw the mice's blood sugar plummet from highly diabetic levels to an even number. She kept double-checking to make sure it wasn't a fluke, but saw the number sustained over the course of months.

Research hits close to home

For Burke, a doctoral candidate studying biomedical engineering, the research hits closer to home. Burke is one such individual for whom daily shots are a well-known part of her life. She was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when she was nine, and for a long time knew she wanted to somehow contribute to the field.

"At my past program, I worked on wound healing for diabetic foot ulcers, which are a complication of Type 1 diabetes," Burke said. "As someone who's 26, I never really want to get there, so I felt like a better strategy would be to focus on how we can treat diabetes now in a more succinct way that mimics the natural occurrences of the pancreas in a non-diabetic person."

The all-Northwestern research team has been working on experiments and publishing studies on islet transplantation for three years, and both Burke and Scott say the work they just published could have been broken into two or three papers. What they've published now, though, they consider a breakthrough and say it could have major implications on the future of diabetes research.

Scott has begun the process of patenting the method and collaborating with industrial partners to ultimately move it into the clinical trials stage. Commercializing his work would address the remaining issues that have arisen for new technologies like Vertex's stem-cell derived pancreatic islets for diabetes treatment.

The paper is titled "Subcutaneous nanotherapy repurposes the immunosuppressive mechanism of rapamycin to enhance allogeneic islet graft viability." Cell research offers diabetes treatment hope