Secretario General de la Real Academia Sueca de Ciencias Goran Hansson, centrar, flanqueado a la izquierda por el miembro del Comité Nobel de Física Thors Hans Hansson, izquierda, y miembro del Comité Nobel de Física John Wettlaufer, Derecha, anuncia los ganadores del Premio Nobel de Física 2021 en la Real Academia de Ciencias de Suecia, en Estocolmo, Suecia, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. El Premio Nobel de Física ha sido otorgado a científicos de Japón, Alemania e Italia. Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann fueron citados por su trabajo en "el modelado físico del clima de la Tierra, cuantificar la variabilidad y predecir de manera confiable el calentamiento global ". La segunda mitad del premio fue otorgada a Giorgio Parisi por" el descubrimiento de la interacción del desorden y las fluctuaciones en los sistemas físicos desde escalas atómicas a planetarias ". Crédito:Pontus Lundahl / TT vía AP

Tres científicos ganaron el Premio Nobel de Física el martes por su trabajo que encontró orden en un aparente desorden. ayudar a explicar y predecir fuerzas complejas de la naturaleza, incluida la ampliación de nuestra comprensión del cambio climático.

Syukuro Manabe, originalmente de Japón, y Klaus Hasselmann de Alemania fueron citados por su trabajo en el desarrollo de modelos de pronóstico del clima de la Tierra y "predecir confiablemente el calentamiento global". La segunda mitad del premio fue para Giorgio Parisi de Italia por explicar el desorden en los sistemas físicos, desde aquellos tan pequeños como el interior de los átomos hasta los del tamaño de un planeta.

Hasselmann dijo a The Associated Press que "preferiría no tener calentamiento global ni premio Nobel".

Manabe dijo que averiguar la física detrás del cambio climático era "1, 000 veces "más fácil que lograr que el mundo haga algo al respecto. Dijo que las complejidades de las políticas y la sociedad son mucho más difíciles de comprender que las complejidades del dióxido de carbono que interactúa con la atmósfera, que luego cambia las condiciones en el océano y en la tierra, que luego altera el aire nuevamente en un ciclo constante.

Llamó al cambio climático "una gran crisis".

El premio llega menos de cuatro semanas antes del inicio de las negociaciones climáticas de alto nivel en Glasgow. Escocia, donde se pedirá a los líderes mundiales que aumenten sus compromisos para frenar el calentamiento global.

Los científicos ganadores del Nobel aprovecharon su momento en el centro de atención para instar a la acción.

"Es muy urgente que tomemos decisiones muy firmes y avancemos a un ritmo muy fuerte" para abordar el calentamiento global, Dijo Parisi. Hizo el llamamiento a pesar de que su parte del premio fue por su trabajo en un área diferente de la física.

Los tres científicos trabajan en lo que se conoce como "sistemas complejos, "del cual el clima es solo un ejemplo. Pero el premio fue para dos campos de estudio que son opuestos en muchos sentidos, aunque comparten el objetivo de dar sentido a lo que parece aleatorio y caótico para que pueda predecirse.

La investigación de Parisi se centra principalmente en partículas subatómicas, predecir cómo se mueven de formas aparentemente caóticas y por qué, y es algo esotérico, mientras que el trabajo de Manabe y Hasselmann trata sobre fuerzas globales a gran escala que dan forma a nuestra vida diaria.

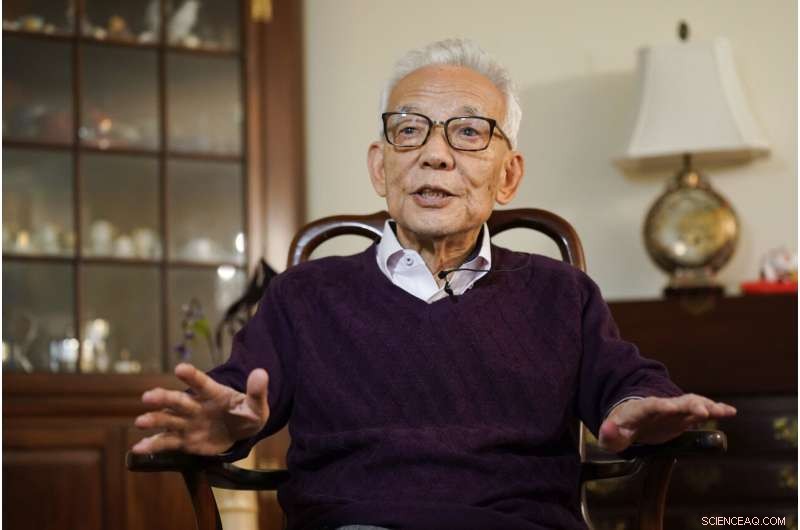

Syukuro Manabe, Derecha, habla con los reporteros en su casa de Princeton, NUEVA JERSEY., Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. Manabe y otros dos científicos han ganado el Premio Nobel de Física por un trabajo que encontró orden en un aparente desorden. ayudar a explicar y predecir fuerzas complejas de la naturaleza, incluida la ampliación de nuestra comprensión del cambio climático. Crédito:Foto AP / Seth Wenig

El físico teórico italiano Giorgio Parisi, centrar, posa para una foto selfie con sus colegas en la Accademia dei Lincei, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021, en Roma, después de recibir el Premio Nobel de Física 2021, junto con Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann, por la Real Academia Sueca de Ciencias en Estocolmo. Crédito:Foto AP / Domenico Stinellis

Los jueces dijeron Manabe, 90, y Hasselmann, 89, "sentó las bases de nuestro conocimiento del clima de la Tierra y cómo las acciones humanas influyen en él".

A partir de la década de 1960, Manabe, ahora con sede en la Universidad de Princeton, creó los primeros modelos climáticos que pronostican lo que sucedería cuando el dióxido de carbono se acumulara en la atmósfera.

Los científicos durante décadas han demostrado que el dióxido de carbono atrapa el calor, pero el trabajo de Manabe ofreció detalles. Permitió a los científicos mostrar eventualmente cómo empeorará el cambio climático y qué tan rápido, dependiendo de la cantidad de contaminación por carbono que se arroje.

Manabe es tan pionero que otros científicos del clima llamaron a su artículo de 1967 con el fallecido Richard Wetherald "el artículo sobre el clima más influyente de todos los tiempos, ", dijo el jefe de modelos climáticos de la NASA, Gavin Schmidt. El colega de Manabe en Princeton, Tom Delworth, llamó a Manabe" el Michael Jordan del clima ".

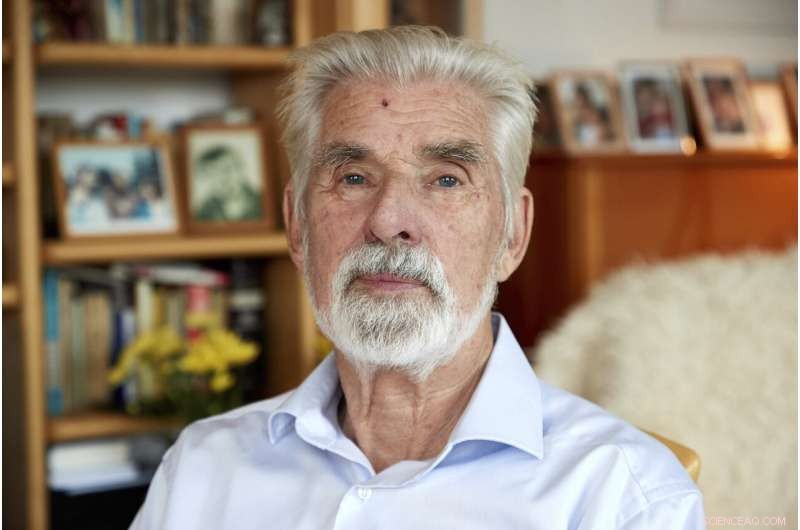

Giorgio Parisi posa para las fotos en Roma, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. El Premio Nobel de Física ha sido otorgado a científicos de Japón, Alemania e Italia. Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann fueron citados por su trabajo en "el modelado físico del clima de la Tierra, cuantificar la variabilidad y predecir de forma fiable el calentamiento global ". La segunda mitad del premio fue otorgada a Giorgio Parisi por" el descubrimiento de la interacción del desorden y las fluctuaciones en los sistemas físicos desde escalas atómicas a planetarias ". Crédito:Cecilia Fabiano / LaPresse vía AP

"Suki preparó el escenario para la ciencia climática actual, no solo la herramienta, sino también cómo usarla, ", dijo su colega científico del clima de Princeton Gabriel Vecchi." No puedo contar las veces que pensé que se me ocurrió algo nuevo, y está en uno de sus papeles ".

Los modelos de Manabe de hace 50 años "predijeron con precisión el calentamiento que realmente ocurrió en las décadas siguientes, ", dijo el científico del clima Zeke Hausfather del Breakthrough Institute. El trabajo de Manabe sirve" como una advertencia para todos nosotros de que debemos tomarnos sus proyecciones de un futuro mucho más cálido si seguimos emitiendo dióxido de carbono con bastante seriedad ".

"Nunca imaginé que esto que comenzaría a estudiar tuviera una consecuencia tan grande, ", Dijo Manabe en una conferencia de prensa en Princeton." Lo estaba haciendo solo por mi curiosidad ".

Aproximadamente una década después del trabajo inicial de Manabe, Hasselmann, del Instituto Max Planck de Meteorología en Hamburgo, Alemania, ayudó a explicar por qué los modelos climáticos pueden ser confiables a pesar de la naturaleza aparentemente caótica del clima. También desarrolló formas de buscar signos específicos de influencia humana en el clima.

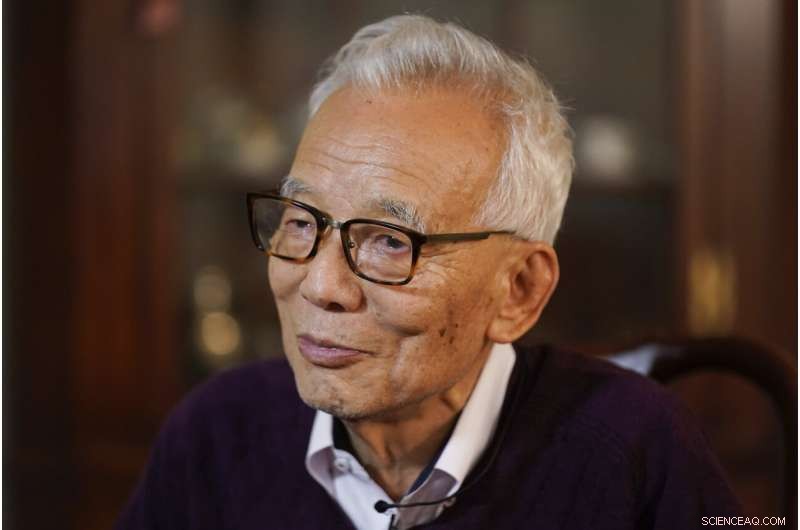

El investigador climático Klaus Hasselmann se encuentra en el balcón de su apartamento en Hamburgo, Alemania, Martes, 5 de octubre, 2021. El Premio Nobel de Física de este año es para el alemán Klaus Hasselmann, Syukuro Manabe (EE. UU.) Y el italiano Giorgio Parisi por los modelos físicos del clima de la Tierra. Crédito:Georg Wendt / dpa vía AP

Mientras tanto, Parisi, de la Universidad Sapienza de Roma, "construyó un modelo físico y matemático profundo" que hizo posible comprender sistemas complejos en campos tan diferentes como las matemáticas, biología, neurociencia y aprendizaje automático.

Su trabajo originalmente se centró en el llamado vidrio giratorio, un tipo de aleación de metal cuyo comportamiento desconcertó durante mucho tiempo a los científicos. Parisi, 73, descubrió patrones ocultos que explicaban su forma de actuar, crear teorías que puedan aplicarse a otros campos de investigación, también.

Los tres físicos utilizaron matemáticas complejas para explicar y predecir lo que parecían fuerzas caóticas de la naturaleza. Eso se conoce como modelado.

"Los modelos climáticos basados en la física hicieron posible predecir la cantidad y el ritmo del calentamiento global, incluidas algunas de las consecuencias, como la subida del nivel del mar, aumento de los eventos de lluvia extrema y huracanes más fuertes, décadas antes de que pudieran ser observados, ", dijo el científico climático y modelador alemán Stefan Rahmstorf. Llamó a Hasselmann y Manabe pioneros en este campo.

El físico teórico italiano Giorgio Parisi habla con los periodistas cuando llega a la Accademia dei Lincei, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021, en Roma, después de recibir el Premio Nobel de Física 2021, junto con Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann, por la Real Academia Sueca de Ciencias en Estocolmo. Crédito:Foto AP / Domenico Stinellis

Cuando los científicos climáticos del Panel Intergubernamental sobre Cambio Climático de las Naciones Unidas y el exvicepresidente de los Estados Unidos Al Gore ganaron el Premio Nobel de la Paz 2007, algunos que niegan el calentamiento global lo descartaron como un movimiento político. Quizás anticipando controversias, miembros de la Academia Sueca de Ciencias, que otorga el Nobel, enfatizó que el martes era un premio de ciencias.

"Lo que estamos diciendo es que el modelado del clima se basa sólidamente en la teoría física y la física bien conocida, ", Dijo el físico sueco Thors Hans Hansson en el anuncio.

Para un científico que comercia con predicciones, Hasselmann dijo que el premio lo tomó desprevenido.

"Me sorprendió mucho cuando llamaron, "dijo." Quiero decir, esto es algo que hice hace muchos años ".

Pero Parisi dijo:"Sabía que había una posibilidad nada despreciable" de ganar.

Syukuro Manabe habla con los reporteros en su casa en Princeton, NUEVA JERSEY., Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. Manabe y otros dos científicos han ganado el Premio Nobel de Física por un trabajo que encontró orden en un aparente desorden. ayudar a explicar y predecir fuerzas complejas de la naturaleza, incluida la ampliación de nuestra comprensión del cambio climático. Crédito:Foto AP / Seth Wenig

El físico teórico italiano Giorgio Parisi habla con los periodistas cuando llega a la Accademia dei Lincei, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021, en Roma, después de recibir el Premio Nobel de Física 2021, junto con Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann, por la Real Academia Sueca de Ciencias en Estocolmo. Crédito:Foto AP / Domenico Stinellis

Syukuro Manabe habla con los reporteros en su casa en Princeton, NUEVA JERSEY., Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. Manabe y otros dos científicos han ganado el Premio Nobel de Física por un trabajo que encontró orden en un aparente desorden. ayudar a explicar y predecir fuerzas complejas de la naturaleza, incluida la ampliación de nuestra comprensión del cambio climático. Crédito:Foto AP / Seth Wenig

El investigador climático Klaus Hasselmann se sienta en su apartamento en Hamburgo, Alemania, Martes, 5 de octubre, 2021. El Premio Nobel de Física de este año es para el alemán Klaus Hasselmann, Syukuro Manabe (EE. UU.) Y el italiano Giorgio Parisi por los modelos físicos del clima de la Tierra. Crédito:Georg Wendt / dpa vía AP

El científico italiano Giorgio Parisi usa su teléfono en el balcón de su casa en Roma, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. El Premio Nobel de Física ha sido otorgado a científicos de Japón, Alemania e Italia. Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann fueron citados por su trabajo en "el modelado físico del clima de la Tierra, cuantificar la variabilidad y predecir de manera confiable el calentamiento global ". La segunda mitad del premio fue otorgada a Giorgio Parisi por" el descubrimiento de la interacción del desorden y las fluctuaciones en los sistemas físicos desde escalas atómicas a planetarias ". Crédito:AP Photo / Alessandra Tarantino

Giorgio Parisi, centrar, abre una botella de vino espumoso en la institución científica Accademia dei Lincei en Roma, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. El Premio Nobel de Física ha sido otorgado a científicos de Japón, Alemania e Italia. Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann fueron citados por su trabajo en "el modelado físico del clima de la Tierra, cuantificar la variabilidad y predecir de forma fiable el calentamiento global ". La segunda mitad del premio fue otorgada a Giorgio Parisi por" el descubrimiento de la interacción del desorden y las fluctuaciones en los sistemas físicos desde escalas atómicas a planetarias ". Crédito:Cecilia Fabiano / LaPresse vía AP

El físico teórico italiano Giorgio Parisi, Derecha, se pasa llamadas telefónicas del colega Massimo Inguscio, presidente del Consejo Nacional de Investigación de Italia, cuando llega a la Accademia dei Lincei, Martes, 5 de octubre 2021, en Roma, después de recibir el Premio Nobel de Física 2021, junto con Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann, por la Real Academia Sueca de Ciencias en Estocolmo. Crédito:Foto AP / Domenico Stinellis

Los peatones toman copias de una edición adicional del periódico Yomiuri que informa que el científico Syukuro Manabe fue galardonado con el Premio Nobel de Física 2021 en Tokio. Martes, 5 de octubre 2021. Crédito:Foto AP / Koji Sasahara

El premio viene con una medalla de oro y 10 millones de coronas suecas (más de 1,14 millones de dólares). El dinero proviene de un legado dejado por el creador del premio, Inventor sueco Alfred Nobel, quien murió en 1895.

Los lunes, el Nobel de Medicina fue otorgado a los estadounidenses David Julius y Ardem Patapoutian por sus descubrimientos sobre cómo el cuerpo humano percibe la temperatura y el tacto.

En los próximos días se entregarán premios en los campos de la química, literatura, paz y economía.

******

Comunicado de prensa del Comité Nobel:Premio Nobel de Física 2021

La Real Academia de Ciencias de Suecia ha decidido otorgar el Premio Nobel de Física 2021

"por contribuciones innovadoras a nuestra comprensión de los sistemas físicos complejos"

con la mitad conjuntamente para

Syukuro Manabe

Universidad de Princeton, Estados Unidos

Klaus Hasselmann

Instituto Max Planck de Meteorología, Hamburgo Alemania

"para el modelado físico del clima de la Tierra, cuantificar la variabilidad y predecir de forma fiable el calentamiento global "

y la otra mitad a

Giorgio Parisi

Universidad Sapienza de Roma, Italia

"por el descubrimiento de la interacción del desorden y las fluctuaciones en los sistemas físicos desde la escala atómica hasta la planetaria"

Física del clima y otros fenómenos complejos

Tres galardonados comparten el Premio Nobel de Física de este año por sus estudios de fenómenos caóticos y aparentemente aleatorios. Syukuro Manabe y Klaus Hasselmann sentaron las bases de nuestro conocimiento del clima de la Tierra y cómo la humanidad influye en él. Giorgio Parisi es recompensado por sus contribuciones revolucionarias a la teoría de materiales desordenados y procesos aleatorios.

Los sistemas complejos se caracterizan por la aleatoriedad y el desorden y son difíciles de entender. El premio de este año reconoce nuevos métodos para describirlos y predecir su comportamiento a largo plazo.

Un sistema complejo de vital importancia para la humanidad es el clima de la Tierra. Syukuro Manabe demostró cómo el aumento de los niveles de dióxido de carbono en la atmósfera conduce a un aumento de las temperaturas en la superficie de la Tierra. En los años 1960, dirigió el desarrollo de modelos físicos del clima de la Tierra y fue la primera persona en explorar la interacción entre el balance de radiación y el transporte vertical de masas de aire. His work laid the foundation for the development of current climate models.

About ten years later, Klaus Hasselmann created a model that links together weather and climate, thus answering the question of why climate models can be reliable despite weather being changeable and chaotic. He also developed methods for identifying specific signals, huellas dactilares, that both natural phenomena and human activities imprint in he climate. His methods have been used to prove that the increased temperature in the atmosphere is due to human emissions of carbon dioxide.

Around 1980, Giorgio Parisi discovered hidden patterns in disordered complex materials. His discoveries are among the most important contributions to the theory of complex systems. They make it possible to understand and describe many different and apparently entirely random materials and phenomena, not only in physics but also in other, very different areas, such as mathematics, biología, neuroscience and machine learning.

"The discoveries being recognised this year demonstrate that our knowledge about the climate rests on a solid scientific foundation, based on a rigorous analysis of observations. This year's Laureates have all contributed to us gaining deeper insight into the properties and evolution of complex physical systems, " says Thors Hans Hansson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

Popular information

They found hidden patterns in the climate and in other complex phenomena

Three Laureates share this year's Nobel Prize in Physics for their studies of complex phenomena. Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann laid the foundation of our knowledge of the Earth's climate and how humanity influences it. Giorgio Parisi is rewarded for his revolutionary contributions to the theory of disordered and random phenomena.

All complex systems consist of many different inter-acting parts. They have been studied by physicists for a couple of centuries, and can be difficult to describe mathematically – they may have an enormous number of components or be governed by chance. They could also be chaotic, like the weather, where small deviations in initial values result in huge differences at a later stage. This year's Laureates have all contributed to us gaining greater knowledge of such systems and their long-term development.

The Earth's climate is one of many examples of complex systems. Manabe and Hasselmann are awarded the Nobel Prize for their pioneering work on developing climate models. Parisi is rewarded for his theoretical solutions to a vast array of problems in the theory of complex systems.

Syukuro Manabe demonstrated how increased concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere lead to increased temperatures at the surface of the Earth. En los años 1960, he led the development of physical models of the Earth's climate and was the first person to explore the interaction between radiation balance and the vertical transport of air masses. His work laid the foundation for the development of climate models.

About ten years later, Klaus Hasselmann created a model that links together weather and climate, thus answering the question of why climate models can be reliable despite weather being changeable and chaotic. He also developed methods for identifying specific signals, huellas dactilares, that both natural phenomena and human activities imprint in the climate. His methods have been used to prove that the increased temperature in the atmosphere is due to human emissions of carbon dioxide.

Around 1980, Giorgio Parisi discovered hidden patterns in disordered complex materials. His discoveries are among the most important contributions to the theory of complex systems. They make it possible to understand and describe many different and apparently entirely random complex materials and phenomena, not only in physics but also in other, very different areas, such as mathematics, biología, neuroscience and machine learning.

The greenhouse effect is vital to life

Two hundred years ago, French physicist Joseph Fourier studied the energy balance between the sun's radiation towards the ground and the radiation from the ground. He understood the atmosphere's role in this balance; at the Earth's surface, the incoming solar radiation is transformed into outgoing radiation – "dark heat" – which is absorbed by the atmosphere, thus heating it. The atmosphere's protective role is now called the greenhouse effect. This name comes from its similarity to the glass panes of a greenhouse, which allow through the heating rays of the sun, but trap the heat inside. Sin embargo, the radiative processes in the atmosphere are far more complicated.

The task remains the same as that undertaken by Fourier – to investigate the balance between the shortwave solar radiation coming towards our planet and Earth's outgoing longwave, infrared radiation. The details were added by many climate scientists over the following two centuries. Contemporary climate models are incredibly powerful tools, not only for understanding the climate, but also for understanding the global heating for which humans are responsible.

These models are based on the laws of physics and have been developed from models that were used to predict the weather. Weather is described by meteorological quantities such as temperature, precipitation, wind or clouds, and is affected by what happens in the oceans and on land. Climate models are based upon the weather's calculated statistical properties, such as average values, standard deviations, highest and lowest measured values, etcétera. They cannot tell us what the weather will be in Stockholm on 10 December next year, but we can get some idea of what temperature or how much rainfall we can expect on average in Stockholm in December.

Establishing the role of carbon dioxide

The greenhouse effect is essential for life on Earth. It governs temperature because the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – carbon dioxide, methane, water vapour and other gases – first absorb the Earth's infrared radiation and then release this absorbed energy, heating up the surrounding air and the ground below it.

Greenhouse gases actually comprise a very small proportion of the Earth's dry atmosphere, which is largely nitrogen and oxygen – these are 99 per cent by volume. Carbon dioxide is just 0.04 per cent by volume. The most powerful greenhouse gas is water vapour, but we cannot control the concentration of water vapour in the atmosphere, while we can control that of carbon dioxide.

The amount of water vapour in the atmosphere is highly dependent on temperature, leading to a feed-back mechanism. More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere makes it warmer, allowing more water vapour to be held in the air, which increases the greenhouse effect and makes temperatures rise even further. If the carbon dioxide level drops, some of the water vapour will condense and the temperature will fall.

An important first piece of the puzzle about the impact of carbon dioxide came from Swedish researcher and Nobel Laureate Svante Arrhenius. Incidentally, it was his colleague, meteorologist Nils Ekholm who, in 1901, was the first to use the word greenhouse in describing the atmosphere's storage and re-radiation of heat.

Arrhenius understood the physics responsible for the greenhouse effect by the end of the 19th century – that outgoing radiation is proportional to the radiant body's absolute temperature (T) to the power of four (T⁴). The hotter the source of the radiation, the shorter the rays' wavelength. The Sun has a surface temperature of 6, 000°C and primarily emits rays in the visible spectrum. Earth, with a surface temperature of just 15°C, re-radiates infrared radiation that is invisible to us. If the atmosphere did not absorb this radiation, the surface temperature would barely exceed –18°C.

Arrhenius was actually attempting to work out what caused the recently discovered phenomenon of ice ages. He arrived at the conclusion that if the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere halved, this would be enough for the Earth to enter a new ice age. And vice versa – a doubling of the amount of carbon dioxide would increase the temperature by 5–6°C, a result which, somewhat fortuitously, is astoundingly close to current estimates.

Pioneering model for the effect of carbon dioxide

In the 1950s, Japanese atmospheric physicist Syukuro Manabe was one of the young and talented researchers in Tokyo who left Japan, which had been devastated by war, and continued their careers in the US. The aim of Manabes's research, like that of Arrhenius around seventy years earlier, was to understand how increased levels of carbon dioxide can cause increased temperatures. Sin embargo, while Arrhenius had focused on radiation balance, in the 1960s Manabe led work on the development of physical models to incorporate the vertical transport of air masses due to convection, as well as the latent heat of water vapour.

To make these calculations manageable, he chose to reduce the model to one dimension – a vertical column, 40 kilometres up into the atmosphere. Aún así, it took hundreds of valuable computing hours to test the model by varying the levels of gases in the atmosphere. Oxygen and nitrogen had negligible effects on surface temperature, while carbon dioxide had a clear impact:when the level of carbon dioxide doubled, global temperature increased by over 2°C.

The model confirmed that this heating really was due to the increase in carbon dioxide, because it predicted rising temperatures closer to the ground while the upper atmosphere got colder. If variations in solar radiation were responsible for the increase in temperature instead, the entire atmosphere should have been heating at the same time.

Sixty years ago, computers were hundreds of thousands of times slower than they are now, so this model was relatively simple, but Manabe got the key features right. You must always simplify, él dice. You cannot compete with the complexity of nature – there is so much physics involved in every raindrop that it would never be possible to compute absolutely everything. The insights from the onedimensional model led to a climate model in three dimensions, which Manabe published in 1975; this was yet another milestone on the road to understanding the climate's secrets.

Weather is chaotic

About ten years after Manabe, Klaus Hasselmann succeeded in linking together weather and climate by finding a way to outsmart the rapid and chaotic weather changes that were so troublesome for calculations. Our planet has vast shifts in its weather because solar radiation is so unevenly distributed, both geographically and over time. Earth is round, so fewer of the sun's rays reach the higher latitudes than the lower ones around the Equator. Not only this, but the Earth's axis is tilted, producing seasonal differences in incoming radiation. The differences in density between warmer and colder air cause the colossal transports of heat between different latitudes, between ocean and land, between higher and lower air masses, which drive the weather on our planet.

Como todos sabemos, making reliable predictions about the weather for more than the next ten days is a challenge. Two hundred years ago, the renowned French scientist, Pierre-Simon de Laplace, stated that if we just knew the position and speed of all the particles in the universe, it should be possible to both calculate what has happened and what will happen in our world. En principio, this should be true; Newton's three-century old laws of motion, which also describe air transport in the atmosphere, are entirely deterministic – they are not governed by chance.

Sin embargo, nothing could be more wrong when it comes to the weather. This is partly because, en la práctica, it is impossible to be precise enough – to state the air temperature, pressure, humidity or wind conditions for every point in the atmosphere. También, the equations are nonlinear; small deviations in initial values can make a weather system evolve in entirely different ways. Based on the question of whether a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil could cause a tornado in Texas, the phenomenon was named the butterfly effect. En la práctica, this means that it is impossible to produce long-term weather forecasts – the weather is chaotic; this discovery was made in the 1960s by the American meteorologist Edward Lorenz, who laid the foundation of today's chaos theory.

Making sense of noisy data

How can we produce reliable climate models for several decades or hundreds of years into the future, despite weather being a classic example of a chaotic system? Around 1980, Klaus Hasselmann demonstrated how chaotically changing weather phenomena can be described as rapidly changing noise, thus placing long-term climate forecasts on a firm scientific foundation. Es más, he developed methods for identifying human impact on the observed global temperature.

As a young doctoral student in physics in Hamburg, Alemania, in the 1950s, Hasselmann worked on fluid dynamics, then began to develop observations and theoretical models for ocean waves and currents. He moved to California and continued with oceanography, meeting colleagues such as Charles David Keeling, with whom the Hasselmanns started a madrigal choir. Keeling is legendary for beginning, back in 1958, what is now the longest series of atmospheric carbon dioxide measurements at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. Little did Hasselmann know that in his later work he would regularly use the Keeling Curve, which shows changes in the carbon dioxide levels.

Obtaining a climate model from noisy weather data can be illustrated by walking a dog:the dog runs off the lead, backwards and forwards, side to side and around your legs. How can you use the dog's tracks to see whether you are walking or standing still? Or whether you are walking quickly or slowly? The dog's tracks are the changes in the weather, and your walk is the calculated climate. Is it even possible to draw conclusions about long-term trends in the climate using chaotic and noisy weather data?

One additional difficulty is that the fluctuations that influence the climate are extremely variable over time – they may be rapid, such as in wind strength or air temperature, or very slow, such as melting ice sheets and warming oceans. Por ejemplo, uniform heating by just one degree can take a thousand years for the ocean, but just a few weeks for the atmosphere. The decisive trick was incorporating the rapid changes in the weather into the calculations as noise, and showing how this noise affects the climate.

Hasselmann created a stochastic climate model, which means that chance is built into the model. His inspiration came from Albert Einstein's theory of Brownian motion, also called a random walk. Usando esta teoría, Hasselmann demonstrated that the rapidly changing atmosphere can actually cause slow variations in the ocean.

Discerning traces of human impact

Once the model for climate variations was finished, Hasselmann developed methods for identifying human impact on the climate system. He found that the models, along with observations and theoretical considerations, contain adequate information about the properties of noise and signals. Por ejemplo, changes in solar radiation, volcanic particles or levels of greenhouse gases leave unique signals, huellas dactilares, which can be separated out. This method for identifying fingerprints can also be applied to the effect that humans have on the climate system. Hasselman thus cleared the way to further studies of climate change, which have demonstrated traces of human impact on the climate using a large number of independent observations.

Climate models have become increasingly refined as the processes included in the climate's complicated interactions are mapped more thoroughly, not least through satellite measurements and weather observations. The models clearly show an accelerating greenhouse effect; since the mid-19th century, the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have increased by 40 per cent. Earth's atmosphere has not contained this much carbon dioxide for hundreds of thousands of years. Respectivamente, temperature measurements show that the world has heated by 1°C over the past 150 years.

Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann have contributed to the greatest benefit for humankind, in the spirit of Alfred Nobel, by providing a solid physical foundation for our knowledge of Earth's climate. We can no longer say that we did not know – the climate models are unequivocal. Is Earth heating up? Si. Is the cause the increased amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere? Si. Can this be explained solely by natural factors? No. Are humanity's emissions the reason for the increasing temperature? Si.

Methods for disordered systems

Around 1980, Giorgio Parisi presented his discoveries about how apparently random phenomena are governed by hidden rules. His work is now considered to be among the most important contributions to the theory of complex systems.

Modern studies of complex systems are rooted in the statistical mechanics developed in the second half of the 19th century by James C. Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann and J. Willard Gibbs, who named this field in 1884. Statistical mechanics evolved from the insight that a new type of method was necessary for describing systems, such as gases or liquids, that consist of large numbers of particles. This method had to take the particles' random movements into account, so the basic idea was to calculate the particles' average effect instead of studying each particle individually. Por ejemplo, the temperature in a gas is a measure of the average value of the energy of the gas particles. Statistical mechanics is a great success, because it provides a microscopic explanation for macroscopic properties in gases and liquids, such as temperature and pressure.

The particles in a gas can be regarded as tiny balls, flying around at speeds that increase with higher temperatures. Cuando baja la temperatura, or pressure increases, the balls first condense into a liquid and then into a solid. This solid is often a crystal, where the balls are organised in a regular pattern. Sin embargo, if this change happens rapidly, the balls may form an irregular pattern that does not change even if the liquid is further cooled or squeezed together. If the experiment is repeated, the balls will assume a new pattern, despite the change happening in exactly the same way. Why are the results different?

Understanding complexity

These compressed balls are a simple model for ordinary glass and for granular materials, such as sand or gravel. Sin embargo, the subject of Parisi's original work was a different kind of system – spin glass. This is a special type of metal alloy in which iron atoms, por ejemplo, are randomly mixed into a grid of copper atoms. Even though there are only a few iron atoms, they change the material's magnetic properties in a radical and very puzzling manner. Each iron atom behaves like a small magnet, o girar, which is affected by the other iron atoms close to it. In an ordinary magnet, all the spins point in the same direction, but in a spin glass they are frustrated; some spin pairs want to point in the same direction and others in the opposite direction – so how do they find an optimal orientation?

In the introduction to his book about spin glass, Parisi writes that studying spin glass is like watching the human tragedies of Shakespeare's plays. If you want to make friends with two people at the same time, but they hate each other, it can be frustrating. This is even more the case in a classical tragedy, where strongly emotional friends and enemies meet on stage. How can the tension in the room be minimised?

Spin glasses and their exotic properties provide a model for complex systems. En los 1970s, many physicists, including several Nobel Laureates, searched for a way to describe the mysterious and frustrating spin glasses. One method they used was the replica trick, a mathematical technique in which many copies, replicas, of the system are processed at the same time. Sin embargo, in terms of physics, the results of the original calculations were unfeasible.

In 1979, Parisi made a decisive breakthrough when he demonstrated how the replica trick could be ingeniously used to solve a spin glass problem. He discovered a hidden structure in the replicas, and found a way to describe it mathematically. It took many years for Parisi's solution to be proven mathematically correct. Desde entonces, his method has been used in many disordered systems and become a cornerstone of the theory of complex systems.

The fruits of frustration are many and varied Both spin glass and granular materials are examples of frustrated systems, in which various constituents must arrange themselves in a manner that is a compromise between counteracting forces. The question is how they behave and what the results are. Parisi is a master at answering these questions for many different materials and phenomena. His fundamental discoveries about the structure of spin glasses were so deep that they not only influenced physics, but also mathematics, biología, neuroscience and machine learning, because all these fields include problems that are directly related to frustration.

Parisi has also studied many other phenomena in which random processes play a decisive role in how structures are created and how they develop, and dealt with questions such as:Why do we have periodically recurring ice ages? Is there a more general mathematical description of chaos and turbulent systems? Or – how do patterns arise in a murmuration of thousands of starlings? This question may seem far removed from spin glass. Sin embargo, Parisi has said that most of his research has dealt with how simple behaviours give rise to complex collective behaviours, and this applies to both spin glasses and starlings.

Advanced information:www.nobelprize.org/prizes/phys … dvanced-information/

© 2021 The Associated Press. Reservados todos los derechos. Este material puede no ser publicado, transmisión, reescrito o redistribuido sin permiso.