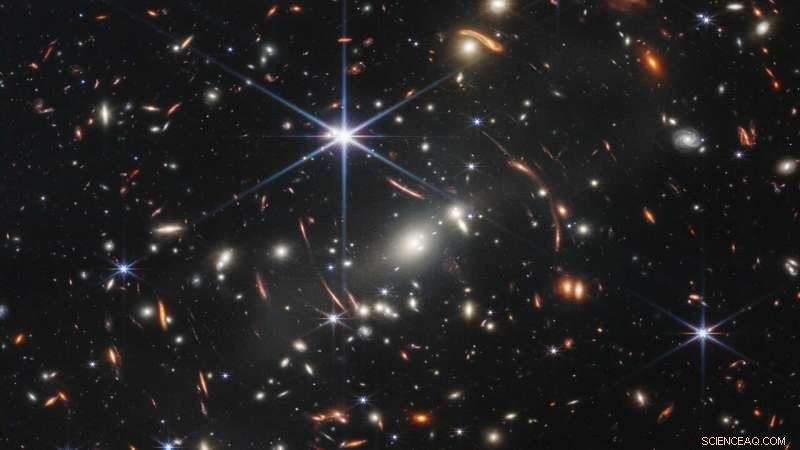

Esta imagen, la primera publicada por el telescopio espacial James Webb de la NASA, muestra el cúmulo de galaxias SMACS 0723. Algunas de las galaxias aparecen manchadas o estiradas debido a un fenómeno llamado lente gravitacional. Este efecto puede ayudar a los científicos a mapear la presencia de materia oscura en el universo. Crédito:NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

¿Podría resolverse uno de los mayores acertijos de la astrofísica reelaborando la teoría de la gravedad de Albert Einstein? Un nuevo estudio en coautoría de científicos de la NASA dice que todavía no.

El universo se está expandiendo a un ritmo acelerado y los científicos no saben por qué. Este fenómeno parece contradecir todo lo que los investigadores entienden sobre el efecto de la gravedad en el cosmos:es como si arrojaras una manzana al aire y continuara hacia arriba, cada vez más rápido. La causa de la aceleración, denominada energía oscura, sigue siendo un misterio.

Un nuevo estudio del Dark Energy Survey internacional, utilizando el Telescopio Victor M. Blanco de 4 metros en Chile, marca el último esfuerzo para determinar si todo esto es simplemente un malentendido:las expectativas de cómo funciona la gravedad a la escala de todo el universo están defectuosos o incompletos. Este posible malentendido podría ayudar a los científicos a explicar la energía oscura. Pero el estudio, una de las pruebas más precisas hasta el momento de la teoría de la gravedad de Albert Einstein a escalas cósmicas, encuentra que la comprensión actual aún parece ser correcta.

Los resultados, escritos por un grupo de científicos que incluye algunos del Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro de la NASA, se presentaron el miércoles 23 de agosto en la Conferencia Internacional sobre Física de Partículas y Cosmología (COSMO'22) en Río de Janeiro. El trabajo ayuda a preparar el escenario para dos próximos telescopios espaciales que probarán nuestra comprensión de la gravedad con una precisión aún mayor que el nuevo estudio y tal vez finalmente resuelvan el misterio.

Hace más de un siglo, Albert Einstein desarrolló su Teoría de la Relatividad General para describir la gravedad, y hasta ahora ha predicho con precisión todo, desde la órbita de Mercurio hasta la existencia de agujeros negros. Pero si esta teoría no puede explicar la energía oscura, han argumentado algunos científicos, entonces tal vez necesiten modificar algunas de sus ecuaciones o agregar nuevos componentes.

Para averiguar si ese es el caso, los miembros de Dark Energy Survey buscaron evidencia de que la fuerza de la gravedad ha variado a lo largo de la historia del universo o en distancias cósmicas. Un hallazgo positivo indicaría que la teoría de Einstein está incompleta, lo que podría ayudar a explicar la expansión acelerada del universo. También examinaron datos de otros telescopios además de Blanco, incluido el satélite Planck de la ESA (Agencia Espacial Europea), y llegaron a la misma conclusión.

The study finds Einstein's theory still works. So no explanation for dark energy yet. But this research will feed into two upcoming missions:ESA's Euclid mission, slated for launch no earlier than 2023, which has contributions from NASA; and NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, targeted for launch no later than May 2027. Both telescopes will search for changes in the strength of gravity over time or distance.

Blurred Vision

How do scientists know what happened in the universe's past? By looking at distant objects. A light-year is a measure of the distance light can travel in a year (about 6 trillion miles, or about 9.5 trillion kilometers). That means an object one light-year away appears to us as it was one year ago, when the light first left the object. And galaxies billions of light-years away appear to us as they did billions of years ago. The new study looked at galaxies stretching back about 5 billion years in the past. Euclid will peer 8 billion years into the past, and Roman will look back 11 billion years.

The galaxies themselves don't reveal the strength of gravity, but how they look when viewed from Earth does. Most matter in our universe is dark matter, which does not emit, reflect, or otherwise interact with light. While scientists don't know what it's made of, they know it's there, because its gravity gives it away:Large reservoirs of dark matter in our universe warp space itself. As light travels through space, it encounters these portions of warped space, causing images of distant galaxies to appear curved or smeared. This was on display in one of first images released from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope.

Dark Energy Survey scientists search galaxy images for more subtle distortions due to dark matter bending space, an effect called weak gravitational lensing. The strength of gravity determines the size and distribution of dark matter structures, and the size and distribution in turn determine how warped those galaxies appear to us. That's how images can reveal the strength of gravity at different distances from Earth and distant times throughout the universe's history. The group has now measured the shapes of over 100 million galaxies, and so far, the observations match what's predicted by Einstein's theory.

"There is still room to challenge Einstein's theory of gravity, as measurements gets more and more precise," said study co-author Agnès Ferté, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral researcher at JPL. "But we still have so much to do before we're ready for Euclid and Roman. So it's essential we continue to collaborate with scientists around the world on this problem as we've done with the Dark Energy Survey." + Explore further